Thinking out loud

Where we share the insights, questions, and observations that shape our approach.

Kafka transactions - integrating with legacy systems

The article covers setting up and using Kafka transactions, specifically in the context of legacy systems that run on JPA/JMS frameworks. We look at various issues that may occur from using different TransactionManagers and how to properly use these different transactions to achieve desired results. Finally, we analyze how Kafka transactions can be integrated with JTA.

Many legacy applications were built on JMS consumers with the JPA database, relying on transactions to ensure exactly-once delivery. These systems rely on the stability and surety of transactional protocols so that errors are avoided. The problem comes when we try to integrate such systems with newer systems built upon non-JMS/JPA solutions – things like Kafka, MongoDB, etc.

Some of these systems, like MongoDB , actively work to make the integration with legacy JMS/JPA easier. Others, like Kafka, introduce their own solutions to such problems. We will look more deeply into Kafka and the ways we can integrate it with our legacy system.

If you want some introduction to Kafka fundamentals, start with this article covering the basics .

Classic JMS/JPA setup

First, let us do a quick review of the most common setups for legacy systems. They often use JMS to exchange messages between different applications, be it IBM MQ, RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, Artemis, or other JMS providers – these are used with transactions to ensure exactly-once delivery. Messages are then processed in the application, oftentimes saving states in a database via JPA API using Hibernate/Spring Data to do so. Sometimes additional frameworks are used to make the processing easier to write and manage, but in general, the processing may look similar to this example:

@JmsListener(destination = "message.queue")

@Transactional(propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void processMessage(String message) {

exampleService.processMessage(message);

MessageEntity entity = MessageEntity.builder().content(message).build();

messageDao.save(entity);

exampleService.postProcessMessage(entity);

messageDao.save(entity);

jmsProducer.sendMessage(exampleService.createResponse(entity));

}

Messages are read, processed, saved to the database, processed further, updated in the database, and the response is sent to a further JMS queue. It is all done in a transactional context in one of two possible ways:

1) Using a separate JMS and JPA transaction during processing, committing a JPA transaction right before committing JMS.

2) Using JTA to merge JMS and JPA transactions so that both are committed or aborted at the same time.

Both solutions have their upsides and pitfalls; neither of them fully guarantees a lack of duplicates, though JTA definitely gives better guarantees than separate transactions. JTA also does not run into the problem of idempotent consumers, it does, however, come with an overhead. In either case, we may run into problems if we try to integrate this with Kafka.

What are Kafka transactions?

Kafka broker is fast and scalable, but the default mode in which it runs does not hold to exactly-once message delivery guarantee. We may see duplicates, or we may see some messages lost depending on circumstances, something that old legacy systems based on transactions cannot accept. As such, we need to switch Kafka to transactional mode, enabling exactly-once guarantee.

Transactions in Kafka are designed so that they are mainly handled on the producer/message broker side, rather than the consumer side. The consumer is effectively an idempotent reader, while the producer/coordinator handle the transaction.

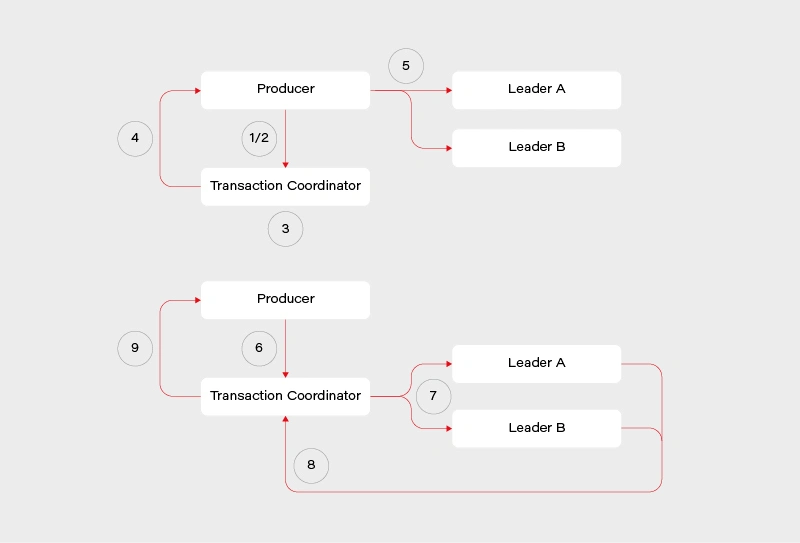

This reduces performance overload on the consumer side, though at the cost of the broker side. The flow looks roughly like this:

1) Determine which broker is the coordinator in the group

2) Producer sends beginTransaction() request to the coordinator

3) The coordinator generates transaction-id

4) Producer receives a response from the coordinator with transaction-id

5) Producer sends its messages to the leading brokers of data partitions together with transaction-id

6) Producer sends commitTransaction() request to the coordinator and awaits the response

7) Coordinator sends commitTransaction() request to every leader broker and awaits their responses

8) Leader brokers set the transaction status to committed for the written records and send the response to the coordinator

9) Coordinator sends transaction result to the producer

This does not contain all the details, explaining everything is beyond the scope of this article and many sources can be found on this. It does however give us a clear view on the transaction process – the main player responsible is the transaction coordinator. It notifies leaders about the state of the transaction and is responsible for propagating the commit. There is some locking involved in the producer/coordinator side that may affect performance negatively depending on the length of our transactions.

Readers, meanwhile, simply operate in read-committed mode, so they will be unable to read messages from transactions that have not been committed.

Kafka transactions - setup and pitfalls

We will look at a practical example of setting up and using Kafka transactions, together with potential pitfalls on the consumer and producer side, also looking at specific ways Kafka transactions work as we go through examples. We will use Spring to set up our Kafka consumer/producer. To do this, we first have to import Kafka into our pom.xml :

<!-- Kafka -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.kafka</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-kafka</artifactId>

</dependency>

To enable transactional processing for the producer, we need to tell Kafka to explicitly enable idempotence, as well as give it transaction-id :

producer:

bootstrap-servers: localhost:9092

transaction-id-prefix: tx-

properties:

enable.idempotence: true

transactional.id: tran-id-1

Each producer needs its own, unique transaction-id , otherwise, we will encounter errors if more than one producer attempts to perform a transaction at the same time. It is crucial to make sure that each instance of an application in a cloud environment has its own unique prefix/transaction-id . Additional setup must also be done for the consumer:

consumer:

bootstrap-servers: localhost:9092

group-id: group_id

auto-offset-reset: earliest

enable-auto-commit: false

isolation-level: read_committed

The properties that interest us set enable-auto-commit to false so that Kafka does not periodically commit transactions on its own. Additionally, we set isolation-level to read committed, so that we will only consume messages when the producer fully commits them. Now both the consumer and the producer are set to exactly-once delivery with transactions.

We can run our consumer and see what happens if an exception is thrown after writing to the queue but before the transaction is fully committed. For this purpose, we will create a very simple REST mapping so that we write several messages to the Kafka topic before throwing an exception:

@PostMapping(value = "/required")

@Transactional(propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void sendMessageRequired() {

producer.sendMessageRequired("Test 1");

producer.sendMessageRequired("Test 2");

throw new RuntimeException("This is a test exception");

}

The result is exactly as expected – the messages are written to the queue but not committed when an exception is thrown. As such the entire transaction is aborted and each batch is aborted as well. This can be seen in the logs:

2021-01-20 19:44:29.776 INFO 11032 --- [io-9001-exec-10] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaProducer : Producing message "Test 1"

2021-01-20 19:44:29.793 INFO 11032 --- [io-9001-exec-10] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaProducer : Producing message "Test 2"

2021-01-20 19:44:29.808 ERROR 11032 --- [producer-tx-1-0] o.s.k.support.LoggingProducerListener : Exception thrown when sending a message with key='key-1-Test 1' and payload='1) Test 1' to topic messages_2:

org.apache.kafka.common.KafkaException: Failing batch since transaction was aborted

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.Sender.maybeSendAndPollTransactionalRequest(Sender.java:422) ~[kafka-clients-2.5.1.jar:na]

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.Sender.runOnce(Sender.java:312) ~[kafka-clients-2.5.1.jar:na]

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.Sender.run(Sender.java:239) ~[kafka-clients-2.5.1.jar:na]

at java.base/java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:834) ~[na:na]

2021-01-20 19:44:29.808 ERROR 11032 --- [producer-tx-1-0] o.s.k.support.LoggingProducerListener : Exception thrown when sending a message with key='key-1-Test 2' and payload='1) Test 2' to topic messages_2:

org.apache.kafka.common.KafkaException: Failing batch since transaction was aborted

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.Sender.maybeSendAndPollTransactionalRequest(Sender.java:422) ~[kafka-clients-2.5.1.jar:na]

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.Sender.runOnce(Sender.java:312) ~[kafka-clients-2.5.1.jar:na]

at org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.internals.Sender.run(Sender.java:239) ~[kafka-clients-2.5.1.jar:na]

at java.base/java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:834) ~[na:na]

The LoggingProducerListener exception contains the key and contents of the message that failed to be sent. The exception tells us that the batch has been failed because the transaction was aborted. Exactly as expected, the entire transaction is atomic so failing it at the end will cause messages successfully written beforehand to not be processed.

We can do the same test for the consumer, the expectation is that the transaction will be rolled back if a message processing error occurs. For that, we will create a simple consumer that will log something and then throw it.

@KafkaListener(topics = "messages_2", groupId = "group_id")

public void consumePartitioned(String message) {

log.info(String.format("Consumed partitioned message \"%s\"", message));

throw new RuntimeException("This is a test exception");

}

We can now use our REST endpoints to send some messages to the consumer. Sure enough, we see the exact behavior we expect – the message is read, the log happens, and then rollback occurs.

2021-01-20 19:48:33.420 INFO 14840 --- [ntainer#0-0-C-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaConsumer : Consumed partitioned message "1) Test 1"

2021-01-20 19:48:33.425 ERROR 14840 --- [ntainer#0-0-C-1] essageListenerContainer$ListenerConsumer : Transaction rolled back

org.springframework.kafka.listener.ListenerExecutionFailedException: Listener method 'public void com.grapeup.kafkatransactions.kafka.KafkaConsumer.consumePartitioned(java.lang.String)' threw exception; nested exception is java.lang.RuntimeException: This is a test exception

at org.springframework.kafka.listener.adapter.MessagingMessageListenerAdapter.invokeHandler(MessagingMessageListenerAdapter.java:350) ~[spring-kafka-2.5.7.RELEASE.jar:2.5.7.RELEASE]

Of course, because of the rollback, the message goes back on the topic. This results in the consumer reading it again, throwing and rolling back, creating an infinite loop that will lock other messages out for this partition. This is a potential issue that we must keep in mind when using Kafka transactions messaging, the same way as we would with JMS. The message will persist if we restart the application or the broker so mindful handling of the exception is required – we need to identify exceptions that require a rollback and those that do not. This is a very-application-specific problem so there is no way to give a clear-cut solution in this article simply because such a solution does not exist.

Last but not least, it is worth noting that propagation works as expected with Spring and Kafka transactions. If we start a new transaction via @Transactional annotation with REQUIRES_NEW propagation, then Kafka will start a new transaction that commits separately from the original one and whose commit/abort result has no effect on the parent one.

There are a few more things we have to keep in mind when working with Kafka transactions, some of them to be expected, others not as much. The first thing is the fact that producer transactions lock down the topic partition that it writes. This can be seen if we run 2 servers and make one transaction delayed. In our case, we started a transaction on server 1 that wrote messages to a topic and then waited 10 seconds to commit the transaction. Server 2 in the meantime wrote its own messages and committed immediately while Server 1 was waiting. The result can be seen in the logs:

Server 1:

2021-01-20 21:38:27.560 INFO 15812 --- [nio-9001-exec-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaProducer : Producing message "Test 1"

2021-01-20 21:38:27.578 INFO 15812 --- [nio-9001-exec-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaProducer : Producing message "Test 2"

Server 2:

2021-01-20 21:38:35.296 INFO 14864 --- [ntainer#0-0-C-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaConsumer : Consumed message "1) Test 1 Sleep"

2021-01-20 21:38:35.308 INFO 14864 --- [p_id.messages.0] o.a.k.c.p.internals.TransactionManager : [Producer clientId=producer-tx-2-group_id.messages.0, transactionalId=tx-2-group_id.messages.0] Discovered group coordinator gu17.ad.grapeup.com:9092 (id: 0 rack: null)

2021-01-20 21:38:35.428 INFO 14864 --- [ntainer#0-0-C-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaConsumer : Consumed message "1) Test 2 Sleep"

2021-01-20 21:38:35.549 INFO 14864 --- [ntainer#0-0-C-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaConsumer : Consumed message "1) Test 1"

2021-01-20 21:38:35.676 INFO 14864 --- [ntainer#0-0-C-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaConsumer : Consumed message "1) Test 2"

Messages were consumed by Server 2 after Server 1 has committed its long-running transaction. Only a partition is locked, not the entire topic – as such, depending on the partitions that producers send messages to, we may encounter full, partial, or no locking at all. The lock is held until the end of the transaction, be it via commit or abort.

Another interesting thing is the order of messages – messages from Server 1 appear before messages from Server 2, even though Server 2 committed its transaction first. This is in contrast to what we would expect from JMS – the messages committed to JMS first would appear first, unlike our example. It should not be a major problem but it is something we must, once again, keep in mind while designing our applications.

Putting it all together

Now that we have Kafka transactions running, we can try and add JMS/JPA configuration to it. We can once again utilize the Spring setup to quickly integrate these. For the sake of the demo, we use an in-memory H2 database and ActiveMQ:

<!-- JPA setup -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-data-jpa</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.h2database</groupId>

<artifactId>h2</artifactId>

<scope>runtime</scope>

</dependency><!-- Active MQ -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-activemq</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.activemq</groupId>

<artifactId>activemq-broker</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.google.code.gson</groupId>

<artifactId>gson</artifactId>

</dependency>

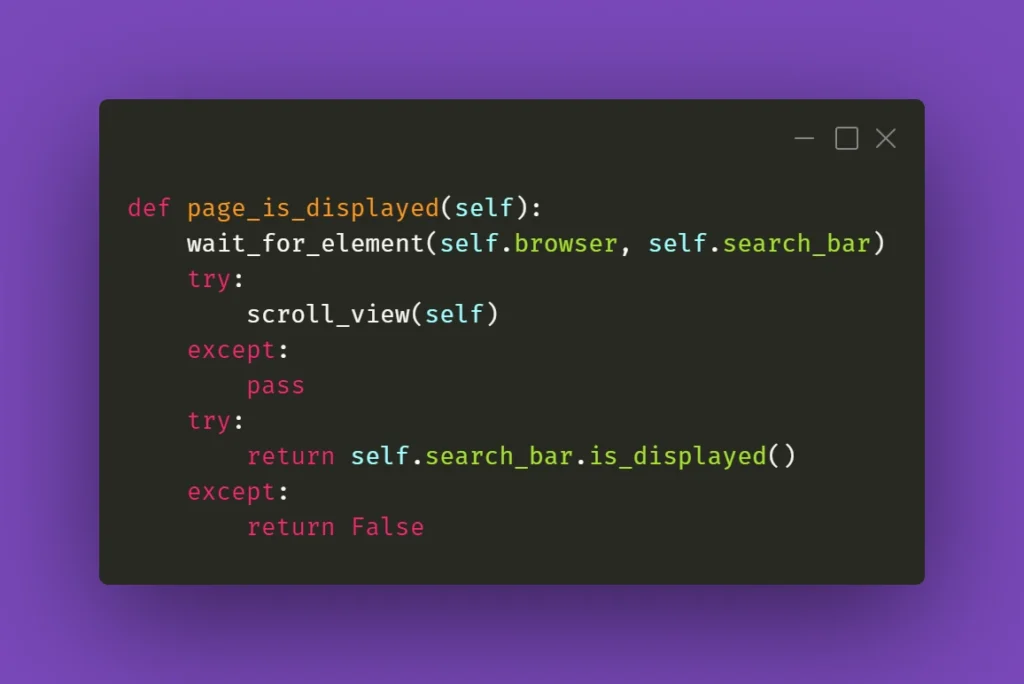

We can set up a simple JMS listener, which reads a message in a transaction, saves something to the database via JPA, and then publishes a further Kafka message. This reflects a common way to try and integrate JMS/JPA with Kafka:

@JmsListener(destination = "message.queue")

@Transactional(propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void processMessage(String message) {

log.info("Received JMS message: {}", message);

messageDao.save(MessageEntity.builder().content(message).build());

kafkaProducer.sendMessageRequired(message);

}

Now if we try running this code, we will run into issues – Spring will protest that it got 2 beans of TransacionManager class. This is because JPA/JMS uses the base TransactionManager and Kafka uses its own KafkaTransactionManager . To properly run this code we have to specify which transaction manager is to be used in which @Transactional annotation. These transaction managers are completely separate and the transactions they start or commit do not affect each other. As such, one can be committed and one aborted if we throw an exception at a correct time. Let’s amend our listener for further analysis:

@JmsListener(destination = "message.queue")

@Transactional(transactionManager = "transactionManager", propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void processMessage(String message) {

log.info("Received JMS message: {}", message);

messageDao.save(MessageEntity.builder().content(message).build());

kafkaProducer.sendMessageRequired(message);

exampleService.processMessage(message);

}

In this example, we correctly mark @Transactional annotation to use a bean named transactionManager , which is the JMS/JPA bean. In a similar way, @Transactional annotation in KafkaProducer is marked to use kafkaTransactionManager , so that Kafka transaction is started and committed within that function. The issue with this code example is the situation, in which ExampleService throws in its processMessage function at line 10.

If such a thing occurs, then the JMS transaction is committed and the message is permanently removed from the queue. The JPA transaction is rolled back, and nothing is actually written to the database despite line 6. The Kafka transaction is committed because no exception was thrown in its scope. We are left with a very peculiar state that would probably need manual fixing.

To minimize such situations we should be very careful about when to start which transaction. Optimally, we would start Kafka transactions right after starting JMS and JPA transactions and commit it right before we commit JPA and JMS. This way we minimize the chance of such a situation occurring (though still cannot fully get rid of it) – the only thing that could cause one transaction to break and not the other is connection failure between commits.

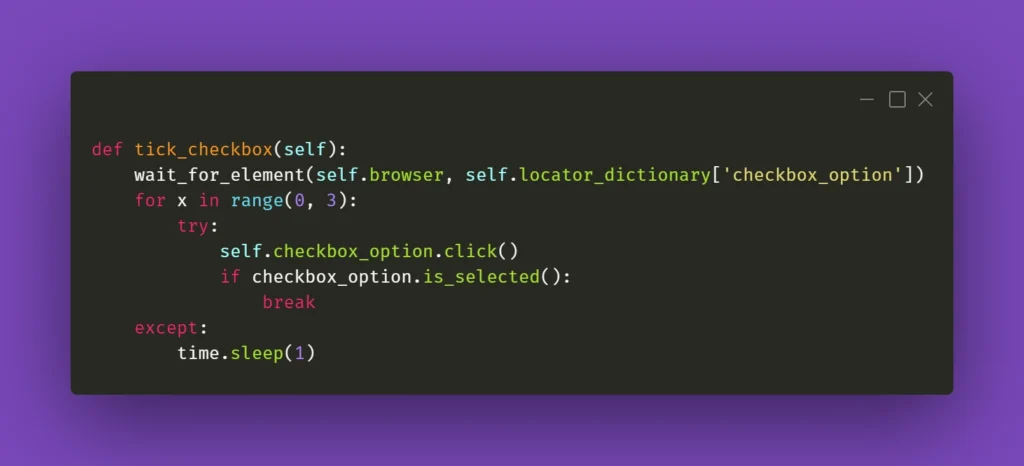

Similar care should be done on the consumer side. If we start a Kafka transaction, do some processing, save to database, send a JMS message, and send a Kafka response in a naive way:

@KafkaListener(topics = "messages_2", groupId = "group_id")

@Transactional(transactionManager = "kafkaTransactionManager", propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void processMessage(String message) {

exampleService.processMessage(message);

MessageEntity entity = MessageEntity.builder().content(message).build();

messageDao.save(entity);

exampleService.postProcessMessage(entity);

messageDao.save(entity);

jmsProducer.sendMessage(message);

kafkaProducer.sendMessageRequired(exampleService.createResponse(entity));

}

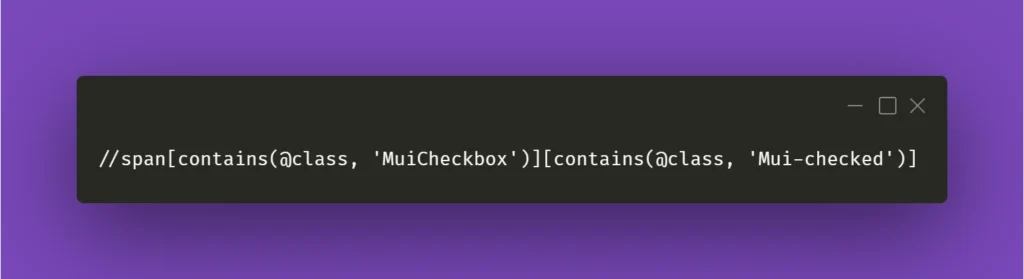

Assuming MessageDAO/JmsProducer start their own transaction in their function, what we will end up with if line 12 throws is a duplicate entry in the database and a duplicate JMS message. The Kafka transaction will be properly rolled back, but the JMS and JPA transactions were already committed, and we will now have to handle the duplicate. What we should do in our case, is to start all transactions immediately and do all of our logic within their scope. One of the solutions to do so, is to create a helper bean that accepts a function to perform within a @Transactional call:

@Service

public class TransactionalHelper {

@Transactional(transactionManager = "transactionManager",

propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void executeInTransaction(Function f) {

f.perform();

}

@Transactional(transactionManager = "kafkaTransactionManager",

propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void executeInKafkaTransaction(Function f) {

f.perform();

}

public interface Function {

void perform();

}

}

This way, our call looks like this:

@KafkaListener(topics = "messages_2", groupId = "group_id")

@Transactional(transactionManager = "kafkaTransactionManager", propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void processMessage(String message) {

transactionalHelper.executeInTransaction(() -> {

exampleService.processMessage(message);

MessageEntity entity = MessageEntity.builder().content(message).build();

messageDao.save(entity);

exampleService.postProcessMessage(entity);

messageDao.save(entity);

jmsProducer.sendMessage(message);

kafkaProducer.sendMessageRequired(exampleService.createResponse(entity));

});

}

Now we start the processing within the Kafka transaction and end it right before the Kafka transaction is committed. This is of course assuming no REQUIRES_NEW propagation is used throughout the inner functions. Once again, in an actual application, we would need to carefully consider transactions in each subsequent function call to make sure that no separate transactions are running without our explicit knowledge and consent.

We will run into a problem, however – the way Spring works, JPA transactions will behave exactly as expected. JMS transaction will be started in JmsProducer anyway and committed on its own. The impact of this could be minimized by moving ExampleService call from line 13 to before line 12, but it’s still an issue we need to keep an eye on. It becomes especially important if we have to write to several different JMS queues as we process our message.

There is no easy way to force Spring to merge JPA/JMS transactions, we would need to use JTA for that.

What can and cannot be done with JTA

JTA has been designed to merge several different transactions, effectively treating them as one. When the JTA transaction ends, each participant votes whether to commit or abort it, with the result of the voting being broadcasted so that participants commit/abort at once. It is not 100% foolproof, we may encounter a connection death during the voting process, which may cause one or more of the participants to perform a different action. The risk, however, is minimal due to the way transactions are handled.

The main benefit of JTA is that we can effectively treat several different transactions as one – this is most often used with JMS and JPA transactions. So the question arises, can we merge Kafka transactions into JTA and treat them all as one? Well, the answer to that is sadly no – the Kafka transactions do not follow JTA API and do not define XA connection factories. We can, however, use JTA to fix the issue we encountered previously between JMS and JPA transactions.

To set up JTA in our application, we do need a provider; however, base Java does not provide an implementation of JTA, only the API itself. There are various providers for this, sometimes coming with the server, Websphere, and its UOP Transaction Manager being a good example. Other times, like with Tomcat, nothing is provided out of the box and we have to use our own. An example of a library that does this is Atomikos – it does have a paid version but for the use of simple JTA, we are good enough with the free one.

Spring made importing Atomikos easy with a starter dependency:

<!-- JTA setup -->

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-jta-atomikos</artifactId>

</dependency>

Spring configures our JPA connection to use JTA on its own; to add JMS to it, however, we have to do some configuration. In one of our @Configuration classes, we should add the following beans:

@Configuration

public class JmsConfig {

@Bean

public ActiveMQXAConnectionFactory connectionFactory() {

ActiveMQXAConnectionFactory connectionFactory = new ActiveMQXAConnectionFactory();

connectionFactory.setBrokerURL("tcp://localhost:61616");

connectionFactory.setPassword("admin");

connectionFactory.setUserName("admin");

connectionFactory.setMaxThreadPoolSize(10);

return connectionFactory;

}

@Bean(initMethod = "init", destroyMethod = "close")

public AtomikosConnectionFactoryBean atomikosConnectionFactory() {

AtomikosConnectionFactoryBean atomikosConnectionFactory = new AtomikosConnectionFactoryBean();

atomikosConnectionFactory.setUniqueResourceName("XA_JMS_ConnectionFactory");

atomikosConnectionFactory.setXaConnectionFactory(connectionFactory());

atomikosConnectionFactory.setMaxPoolSize(10);

return atomikosConnectionFactory;

}

@Bean

public JmsTemplate jmsTemplate() {

JmsTemplate template = new JmsTemplate();

template.setConnectionFactory(atomikosConnectionFactory());

return template;

}

@Bean

public DefaultJmsListenerContainerFactory jmsListenerContainerFactory(PlatformTransactionManager transactionManager) {

DefaultJmsListenerContainerFactory factory = new DefaultJmsListenerContainerFactory();

factory.setConnectionFactory(atomikosConnectionFactory());

factory.setConcurrency("1-1");

factory.setTransactionManager(transactionManager);

return factory;

}

}

We define an ActiveMQXAConnectionFactory , which implements XAConnectionFactory from JTA API. We then define a separate AtomikosConnectionFactory , which uses ActiveMQ one. For all intents and purposes, everything else uses Atomikos connection factory – we set it for JmsTemplate and DefaultJmsListenerContainerFactory . We also set the transaction manager, which will now become the JTA transaction manager.

Having all of that set, we can run our application again and see if we still encounter issues with transactions not behaving as we want them to. Let’s set up a JMS listener with additional logs for clarity:

@JmsListener(destination = "message.queue")

@Transactional(transactionManager = "transactionManager", propagation = Propagation.REQUIRED)

public void processMessage(final String message) {

transactionalHelper.executeInKafkaTransaction(() -> {

MessageEntity entity = MessageEntity.builder().content(message).build();

messageDao.save(entity);

log.info("Saved database entity");

kafkaProducer.sendMessageRequired(message);

log.info("Sent kafka message");

jmsProducer.sendMessage("response.queue", "Response: " + message);

log.info("Sent JMS response");

throw new RuntimeException("This is a test exception");

});

}

We expect that JTA and Kafka transactions will both roll back, nothing will be written to the database, nothing will be written to response.queue , nothing will be written to Kafka topic, and that the message will not be consumed. When we run this, we get the following logs:

2021-01-20 21:56:00.904 INFO 9780 --- [enerContainer-1] c.g.kafkatransactions.jms.JmsConsumer : Saved database entity

2021-01-20 21:56:00.906 INFO 9780 --- [enerContainer-1] c.g.k.kafka.KafkaProducer : Producing message "This is a test message"

2021-01-20 21:56:00.917 INFO 9780 --- [enerContainer-1] c.g.kafkatransactions.jms.JmsConsumer : Sent kafka message

2021-01-20 21:56:00.918 INFO 9780 --- [enerContainer-1] c.g.kafkatransactions.jms.JmsProducer : Sending JMS message: Response: This is a test message

2021-01-20 21:56:00.922 INFO 9780 --- [enerContainer-1] c.g.kafkatransactions.jms.JmsConsumer : Sent JMS response

2021-01-20 21:56:00.935 WARN 9780 --- [enerContainer-1] o.s.j.l.DefaultMessageListenerContainer : Execution of JMS message listener failed, and no ErrorHandler has been set.

org.springframework.jms.listener.adapter.ListenerExecutionFailedException: Listener method 'public void com.grapeup.kafkatransactions.jms.JmsConsumer.processMessage(java.lang.String)' threw exception; nested exception is java.lang.RuntimeException: This is a test exception

at org.springframework.jms.listener.adapter.MessagingMessageListenerAdapter.invokeHandler(MessagingMessageListenerAdapter.java:122) ~[spring-jms-5.2.10.RELEASE.jar:5.2.10.RELEASE]

The exception thrown is followed by several errors about rolled back transactions. After checking our H2 database and looking at Kafka/JMS queues, we can indeed see that everything we expected has been fulfilled. The original JMS message was not consumed either, starting an endless loop which, once again, we would have to take care of in a running application. The key part though is that transactions behaved exactly as we intended them to.

Is JTA worth it for that little bit of surety? Depends on the requirements – do we have to write to several JMS queues simultaneously while writing to the database and Kafka? We will have to use JTA. Can we get away with a single write at the end of the transaction? We might not need to. There is sadly no clear-cut answer, we must use the right tools for the right job.

Summary

We managed to successfully launch Kafka in transactional mode, enabling exactly-once delivery mechanics. This can be integrated with JMS/JPA transactions, although we may encounter problems in our listeners/consumers depending on circumstances. If needed, we may introduce JTA to allow us an easier control of different transactions and whether they are committed or aborted. We used ActiveMQ/H2/Atomikos for this purpose, but this works with any JMS/JPA/JTA providers.

If you're looking for help in mastering cloud technologies , learn how our team works with innovative companies.

Connected car: Challenges and opportunities for the automotive industry

The development of connected car technology accelerated digital disruption in the automotive industry. Verified Market Research valued the connected car market at USD 72.68 billion in 2019 and projected its value to reach USD 215.23 billion by 2027. Along with the rapid growth of this market’s worth, we observe the constant development of new customer-centric services that goes far beyond driving experience.

While the development of connected car technology created a demand for connectivity solutions and drive-assistance systems, companies willing to build their position in this market have to face some significant challenges. This article is the first one of the mini-series that guides you through the main obstacles with building software for connected cars. We start with the basics of a connected vehicle, then dive into the details of prototyping and providing production-ready solutions. Finally, we analyze and predict the future of verticals associated with automotive-rental car enterprises, insurers, and mobility providers.

This series provides you with hands-on knowledge based on our experience in developing production-grade and cutting-edge software for the leading automotive and car rental enterprises. We share our insights and pointers to overcome recurring issues that happen to every software development team working with these technologies.

What is a Connected Car?

A Connected Car is a vehicle that can communicate bidirectionally with other systems outside the car , such as infrastructure, other vehicles, or home/office. Connected cars belong to the expanding environment of devices that comprise the Internet of Things landscape. As well as all devices that are connected to the internet, some functions of a vehicle can be managed remotely.

Along with that, IoT devices are valuable resources of data and information that enable further development of associated services. And while most car owners would describe it as the mobile application paired with a car that allows users to check the fuel level, open/close doors, control air conditioning, and, in some cases, start the ignition, this technology goes much further.

V2C - Vehicle to Cloud

Let’s focus on some real-case scenarios to showcase the capabilities of connected car technology. If a car is connected, it may also have a sat-nav system with a traffic monitoring feature that can alert a driver if there is a traffic jam in front of them and suggest an alternative route. Or maybe there is a storm at the upcoming route and navigation can warn the driver. How does it work?

That is mostly possible thanks to what we call V2C - Vehicle to Cloud communication. Utilizing the fact that a car is connected, and it is sending and gathering data, a driver may also try to find it, in case it was stolen. Telematics data is also helpful to understand the reasons behind an accident on the road - we can analyze what happened before the accident and what may have led to the event. The data can be also used for predictive maintenance, even if the rules managing the dates are changing dynamically.

While this seems just like a nice-to-have feature for the drivers, it allows car manufacturers to provide an extensive set of subscription-based features and functionalities for the end-users. The availability of services may depend on the current car state - location, temperature, and technical availability. As an example: during the winter, if the car is equipped with heated seats and the temperature drops under 0 Celsius, but the subscription for this feature expires, the infotainment can propose to buy the new one - which is more tempting when the user is at this time cold.

V2I - Vehicle to Infrastructure

A vehicle equipped with connected car technology is not limited to communicating only with the cloud. Such a car is capable of exchanging data and information with road infrastructure, and this functionality is called V2I - Vehicle to Infrastructure communication. A car processes information from infrastructure components - road signs, lane markings, traffic lights to support the driving experience by suggesting decision makings. In the next steps, V2I can provide drivers with information about traffic jams and free parking spots.

Currently, in Stuttgart, Germany, the city’s infrastructure provides the data live traffic lights data for vehicle manufacturers, so drivers can see not just what light is on, but how long they have to wait for the red light to switch to green again. This part of connected car technology can rapidly develop with the utilization of wireless communication and the digitalization of road infrastructure.

V2V - Vehicle to Vehicle

Another highly valuable type of communication provided by connected car technology is V2V - Vehicle to Vehicle. By developing an environment in which numerous cars are able to wirelessly exchange data, the automotive industry offers a new experience - every vehicle can use the information provided by a car belonging to the network, which leads to more effective communication covering traffic, car parking, alternative routes, issues on the road, or even some worth-seeing spots.

It may also significantly increase safety on the road, when one car notifies another that drives a few hundred meters behind him that it just had a hard breaking or that the road surface is slippery, using the information from ABS, ESP, or TC systems. That has not just an informational value but is also used for Adaptive Cruise Control or Travel Assist systems and reduces the speed of vehicles automatically increasing the safety of the travelers. V2V communication makes use of network and scale effects - the more users have connected to the network, the more helpful and complete information the network provides.

The list of use cases for connected car technology is only limited by our imagination but is excelling rapidly as many teams are joining the movement aiming to transform the way we travel and communicate. The Connected Car revolution leads to many changes and impacts both user experience and business models of the associated industries.

How connected car technology impacts business models of the automotive industry

Connected cars bring innovative solutions to the whole environment comprising the automotive landscape. Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) have gained new revenue streams. Now vehicles allow their users to access stores and purchase numerous features and associated services that enhance customer experience, such as infotainment systems. By delivering aftermarket services directly to a car, the automotive industry monetizes new channels. Furthermore, these systems enable automakers to deliver advertisements, which become an increasing source of revenue.

The development of new technology in automotive creates a similar change as we observed in the mobile phone market. When smartphones equipped with operating systems had become a new normal, significantly increased the number of new apps that now allow their users to manage numerous services and tasks using the device.

But it is just an introduction to numerous business opportunities provided by connected cars. Since data has become a new competitive advantage that fuels the digital economy, collecting and distributing data about user behavior and vehicle performance is seen as highly profitable, especially when taking into account the potential interest of insurers providers.

Assembled data while used properly gives OEMs powerful insights into customer behavior that should lead to the rapid growth of new technologies and products improving customer experiences, such as predictive maintenance or fleet management.

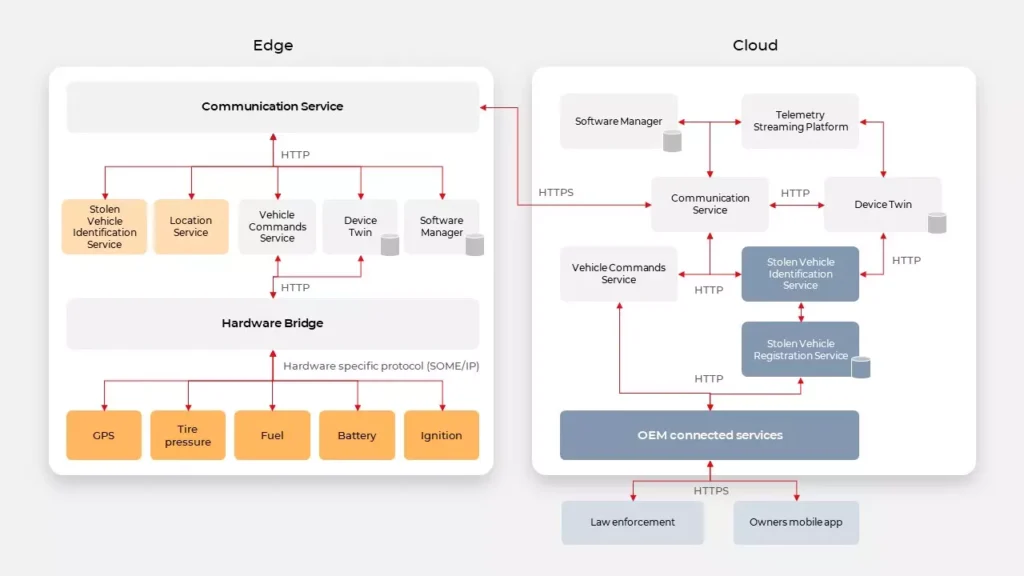

The architecture behind connected car technology

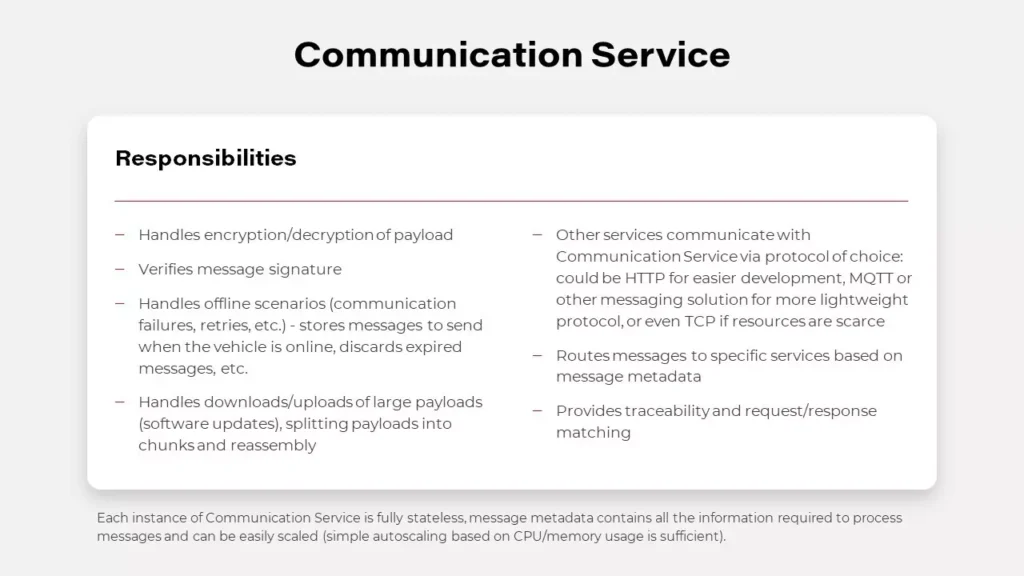

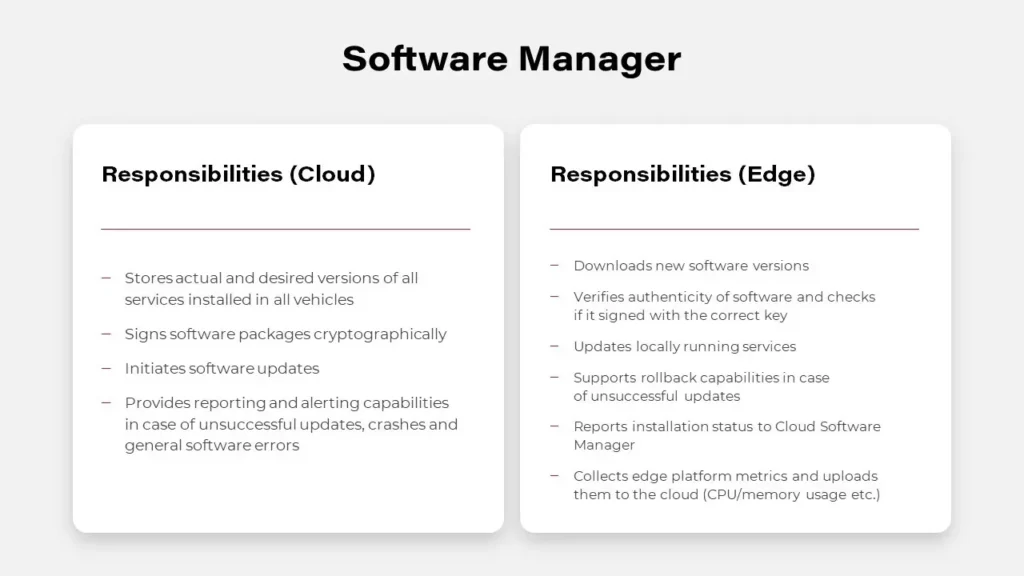

Automotive companies utilize data from vehicle sensors and allow 3rd party providers to access their systems through dedicated API layers. Let’s dive into such architecture.

High-Level Architecture

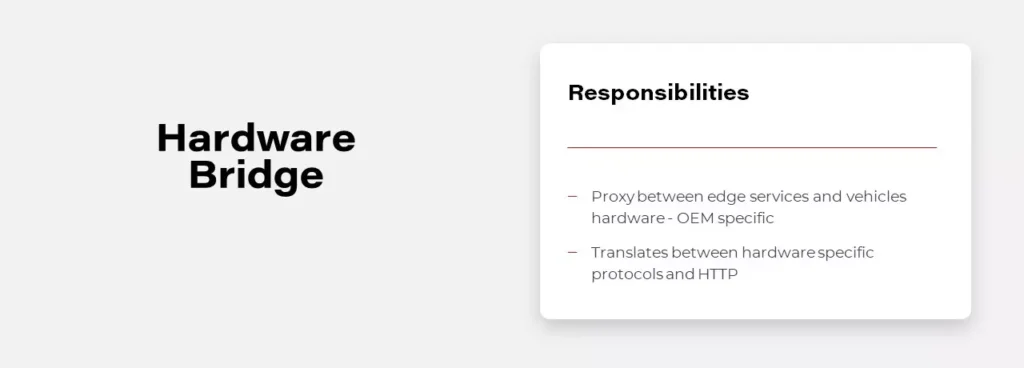

System components

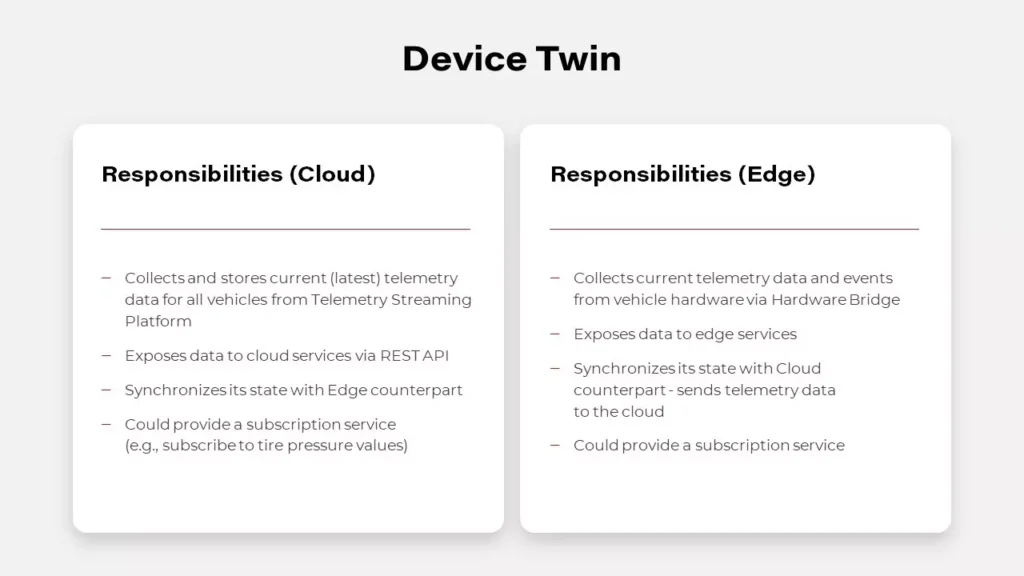

Digital Twin in automotive

A digital twin is a virtual replica and software representation of a product, system, or process. This concept is being adopted and developed in the automotive industry, as carmakers utilize its powerful capabilities to increase customer satisfaction, improve the way they develop vehicles and their systems, and innovate. A digital twin empowers automotive companies to collect various information from numerous sensors, as this tool allows to capture operational and behavioral data generated by a vehicle. Equipped with these insights, the leading automotive enterprises work on enhancing performance and customize user experience, but meanwhile, they have to tackle significant challenges.

First of all, getting data from vehicles is problematic. Hardware built-in vehicles have particular limits, which leads to reduced capabilities in providing software. Unlike software, once shipped hardware cannot be easily adjusted to the changing conditions and works for several years at least. Furthermore, while willing to deliver a customer-centric experience, automakers still have to protect their users from numerous threats. To protect vehicles from denial of service attacks, vehicles can throttle the number of requests. Overall, it’s a good idea but can have a terrible impact when multiple applications are trying to get data from vehicles, e.g., in the rental domain. This complex problem can be simply solved by Digital Twin. It can expose data to all applications without them needing to connect to the vehicle by simply gathering all real-time vehicle data in the cloud.

Implementation of this pattern is possible by using NoSQL databases like MongoDB or Cassandra and reliable communication layers, examples are described below. Digital Twin may be implemented in two possible ways, uni- or bidirectional.

Unidirectional Digital Twin

Unidirectional Digital Twin is saving only values received from the vehicle, in case of conflict it resolves the situation based on event timestamp. However, it doesn’t mean that the event causing the conflict is discarded and lost, usually every event is sent to the data platform. The data platform is a useful concept for data analysis and became handy when implementing complex use cases like analyzing driver habits.

Bidirectional Digital Twin

The Bidirectional Digital Twin design is based on the concept of the current and desired state. The vehicle is reporting the current state to the platform, and on the other hand, the platform is trying to change the state in the vehicle to the desired value. In this situation, in case of conflict, not only the timestamp matters as some operations from the cloud may not be applied to the vehicle in every state, eg., the engine can’t be disabled when the vehicle is moving.

However, meeting the goal of developing a Digital Twin may be tricky though as it all depends on the OEM and provided API. Sometimes it doesn’t expose enough properties or doesn’t provide real-time updates. In such cases, it may be even impossible to implement this pattern.

API

At first, designing a Connected Car API isn’t different from designing an API for any other backend system. It should start with an in-depth analysis of a domain, in this case, automotive. Then user stories should be written down, and with that, the development team should be able to find common parts and requirements to be able to determine the most suitable communication protocol. There are a lot of possible solutions to choose from. There are several reliable and high-traffic oriented message brokers like Kafka or hosted solutions AWS Kinesis. However, the simplest solution based on HTTP can also handle the most complex cases when used with Server-Sent Events or WebSockets. When designing API for mobile applications, we should also consider implementing push notifications for a better user experience.

When designing API in the IoT ecosystem, you can’t rely too much on your connection with edge devices. There are a lot of connectivity challenges, for example, a weak cellular range. You can’t guarantee when your command to a car will be delivered, and if a car will respond in milliseconds or even at all. One of the best patterns here is to provide the asynchronous API. It doesn’t matter on which layer you’re building your software if it’s a connector between vehicle and cloud or a system communicating with the vehicle’s API provider. Asynchronous API allows you to limit your resource consumption and avoid timeouts that leave systems in an unknown state. It’s a good practice to include a connector, the logic which handles all connection flaws. Well designed and developed connectors should be responsible for retries, throttling, batching, and caching of request and response.

OEM’s are now implementing a unified API concept that enables its customers to communicate with their cars through the cloud at the same quality level as when they use direct connections (for example using Wi-Fi). This means that the developer sees no difference in communicating with the car directly or using the cloud. What‘s also worth noting: the unified API works well with the Digital Twin concept, which leads to cuts in communication with the vehicle as third-party apps are able to connect with the services in the cloud instead of communicating directly with an in-car software component.

What’s next for connected car technology

Once the challenges become tackled, connected vehicles provide automakers and adjacent industries with a chance to establish beneficial co-operations, build new revenue streams, or even create completely new business models. The possibilities delivered thanks to over-the-air communication (OTA) allowing to send fixes, updates, and upgrades to already sold cars, provide new monetization channels, and sustain customer relationships.

As previously mentioned, the global connected car market is projected to reach USD 215.23 billion by 2027. To acquire shares in this market, automotive companies are determined to adjust their processes and operations. Among key factors that impact the development of connected car technology, we can point out a few crucial. The average lifecycle of a car is about 10 years. Today, automakers make decisions regarding connected cars that will go into production two to four years from now. For the cellular connectivity strategy to remain relevant over 12 to 15 years, significant challenges and assumptions need to be collaboratively addressed by OEMs, telematics control unit suppliers, and service providers.

Automakers must manage software in the field reliably, cost-efficiently, and, most importantly, securely – not just patch fixes, but also continually upgrade and enhance the functionality. The availability of OTA updates reduces the burden on dealerships and certified repair centers but requires better and more extensive testing, as the breakage of critical features is not an option.

Cellular solutions need to be agile to be compatible with emerging network technologies over the vehicle lifetime, e.g., 5G to be the industry standard in the next few years. The chosen solution must deliver reliable, seamless, uninterrupted coverage in all countries and markets where the vehicles are sold and driven.

Solution developers must offer scalable, cost-effective ways to develop upgradeable software that can be universally deployed across technologies, hardware, and chipsets. A huge focus must be put on testing the changes automatically on both the cloud platform side and the vehicle side.

As Connected Vehicles proliferate, the auto industry will need to adapt and transform itself into the growing technological dependency. OEMs and Tier-1 manufacturers must partner with technology specialists to thrive in an era of software-defined vehicles. As connectivity requires skills and capabilities outside of the OEMs’ domain, automakers will necessarily have to be software developers. An open platform environment will go a long way to encourage external developers to design apps for vehicle connectivity platforms.

Apache Kafka fundamentals

Nowadays, we have plenty of unique architectural solutions. But all of them have one thing in common – every single decision should be done after a solid understanding of the business case as well as the communication structure in a company. It is strictly connected with famous Conway’s Law:

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.”

In this article, we go deeper into the Event-Driven style, and we discover when we should implement such solutions. This is when Kafka comes to play.

The basic definition taken from the Apache Kafka site states that this is an open-source distributed event streaming platform . But what exactly does it mean? We explain the basic concepts of Apache Kafka, how to use the platform, and when we may need it.

Apache Kafka is all about events

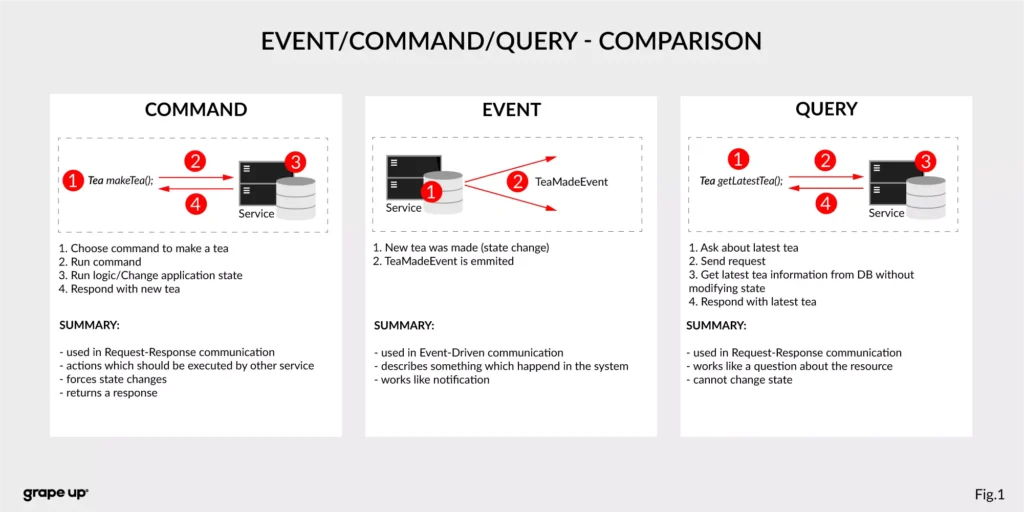

To understand what the event streaming platform is, we need to have a prior understanding of an event itself. There are different ways of how the services can interact with each other – they can use Commands, Events, or Queries. So, what is the difference between them?

- Command – we can call it a message in which we expect something to be done - like in the army when the commander gives an order to soldiers. In computer science, we are making requests to other services to perform some action, which causes a system state change. The crucial part is that they are synchronous, and we expect that something will happen in the future. It is the most common and natural method for communication between services. On the other hand, you do not really know if your expectation will be fulfilled by the service. Sometimes we create commands, and we do not expect any response (it is not needed for the caller.)

- Event – the best definition of an event is a fact. It is a representation of the change which happened in the service (domain). It is essential that there is no expectation of any future action. We can treat an event as a notification of state change. Events are immutable. In other words - it is everything necessary for the business. This is also a single source of truth, so events need to precisely describe what happened in the system.

- Query – in comparison to the others, the query is only returning a response without any modifications in the system state. A good example of how it works can be an SQL query.

Below there is a small summary which compares all the above-mentioned ways of interaction:

Now we know what the event is in comparison to other interaction styles. But what is the advantage of using events? To understand why event-driven solutions are better than synchronous request-response calls, we have to learn a bit about software architecture history.

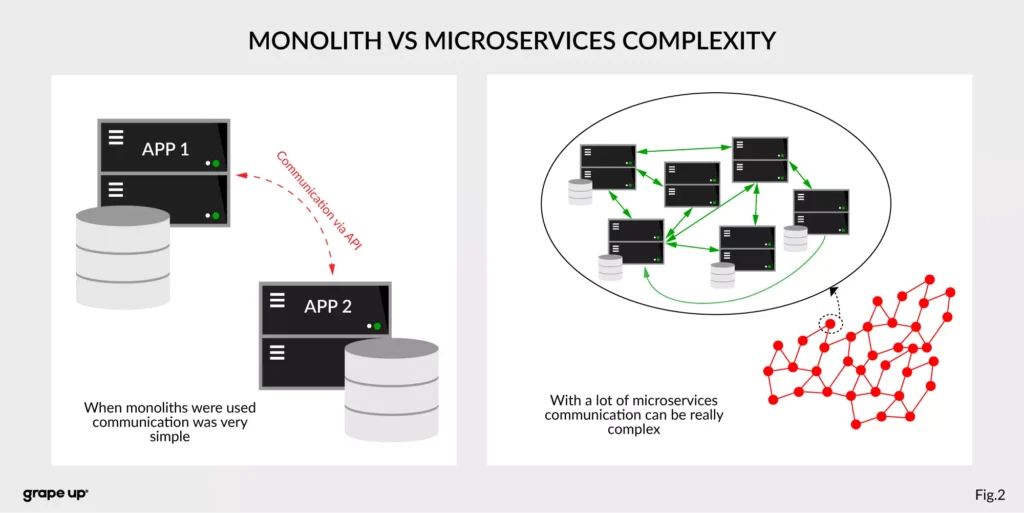

The figure describes a difference between a system that has old monolith architecture and a system with new modern microservice architecture.

The left side of the figure presents an API communication between two monoliths. In this case, communication is straightforward and easy. There is a different problem though such monolith solutions are very complex and hard to maintain.

The question is, what happens if we want to use, instead of two big services, a few thousands of small microservices . How complex will it be? The directed graph on the right side is showing how quickly the number of calls in the system can grow, and with it, the number of shared resources. We can have a situation when we need to use data from one microservice in many places. That produces new challenges regarding communication.

What about communication style?

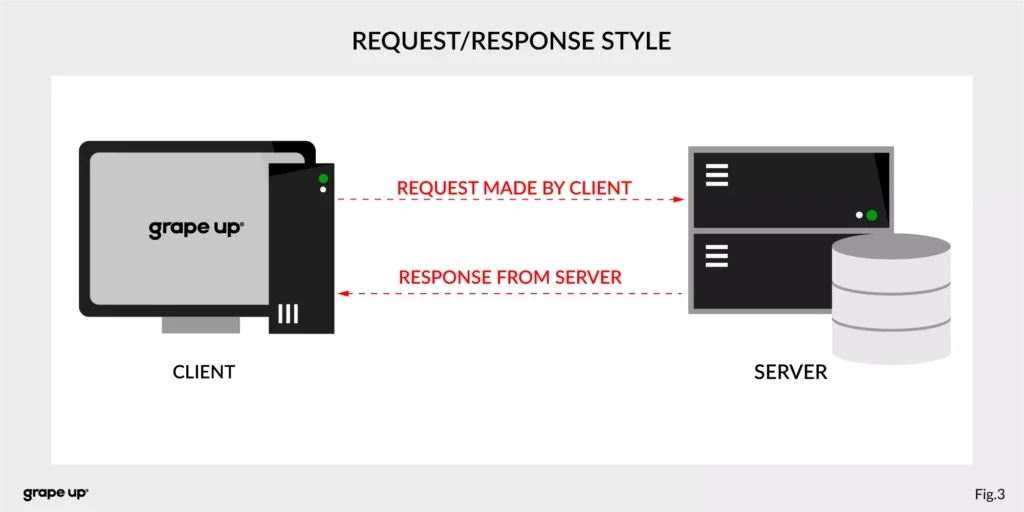

In both cases, we are using a request-response style of communication (figure below), and we need to know how to use API provided by the server from the caller perspective. There must be some kind of protocol to exchange messages between services.

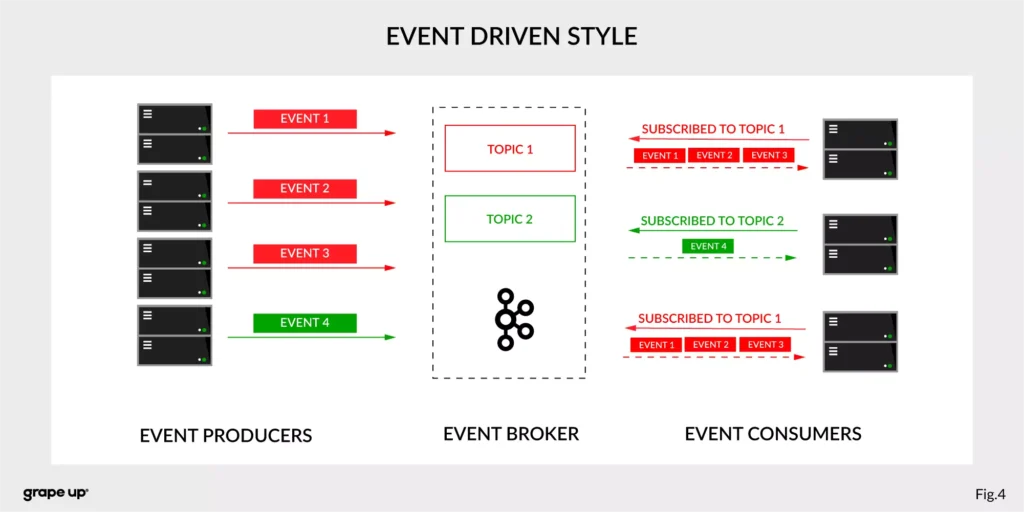

So how to reduce the complexity and make an integration between services easier? To answer this – look at the figure below.

In this case, interactions between event producers and consumers are driven by events only. This pattern supports loose coupling between services, and what is more important for us, the event producer does not need to be aware of the event consumer state. It is the essence of the pattern. From the producer's perspective, we do not need to know who or how to use data from the topic.

Of course, as usual, everything is relative. It is not like the event-driven style is always the best. It depends on the use case. For instance, when operations should be done synchronously, then it is natural to use the request-response style. In situations like user authentication, reporting AB tests, or integration with third-party services, it is better to use a synchronous style. When the loose coupling is a need, then it is better to go with an event-driven approach. In larger systems, we are mixing styles to achieve a business goal.

The name of Kafka has its origins in the word Kafkaesque which means according to the Cambridge dictionary something extremely unpleasant, frightening, and confusing, and similar to situations described in the novels of Franz Kafka.

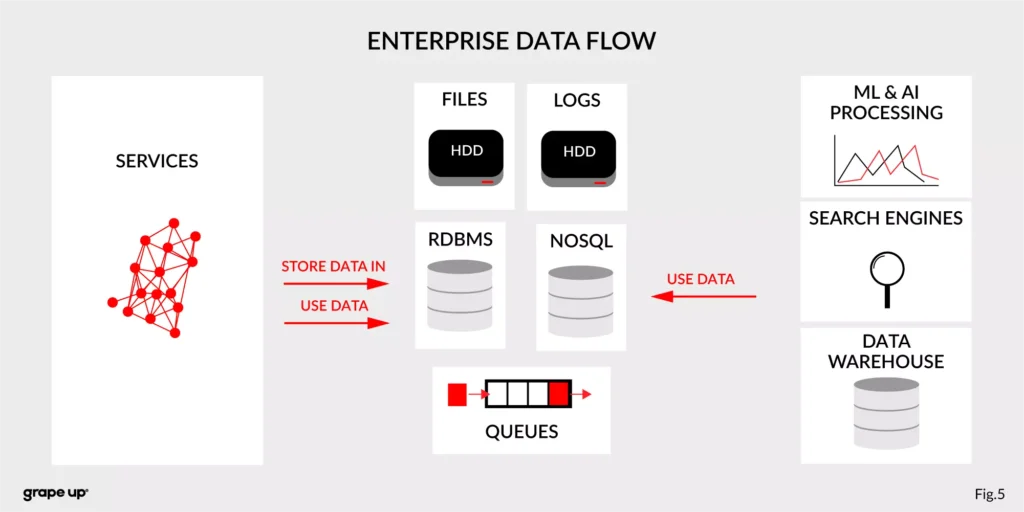

The communication mess in the modern enterprise was a factor to invent such a tool. To understand why - we need to take a closer look at modern enterprise systems.

The modern enterprise systems contain more than just services. They usually have a data warehouse, AI and ML analytics, search engines, and much more. The format of data and the place where data is stored are various – sometimes a part of the data is stored in RDBMS, a part in NoSQL, and other in file bucket or transferred via a queue. They can have different formats and extensions like XML, JSON, and so on. Data management is the key to every successful enterprise. That is why we should care about it. Tim O’Reilly once said:

„We are entering a new world in which data may be more important than software.”

In this case, having a good solution for processing crucial data streams across an enterprise is a must to be successful in business. But as we all know, it is not always so easy.

How to tame the beast?

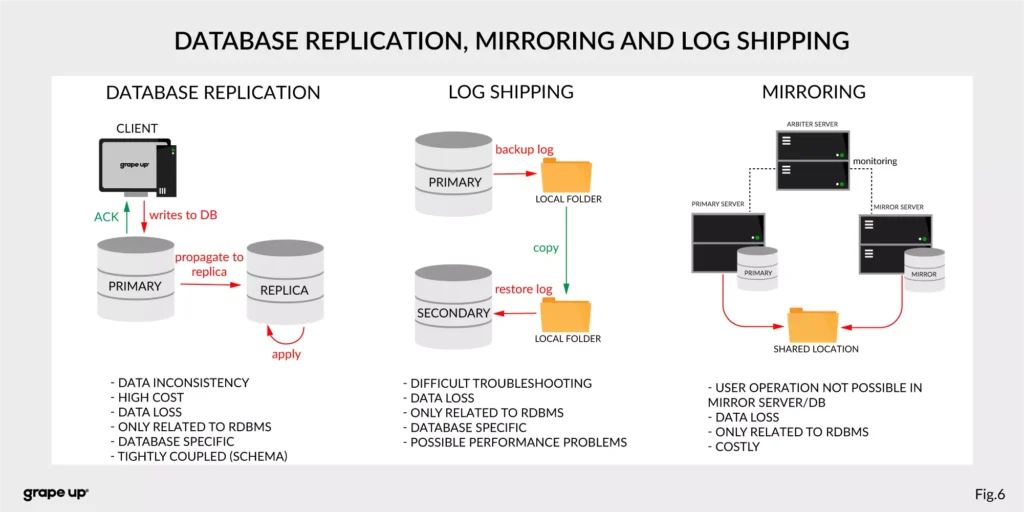

For this complex enterprise data flow scenario, people invented many tools/methods. All to make this enterprise data distribution possible. Unfortunately, as usual, to use them, we have to make some tradeoffs. Here we have a list of them:

- Database replication, Mirroring, and Log Shipping - used to increase the performance of an application (scaling) and backup/recovery.

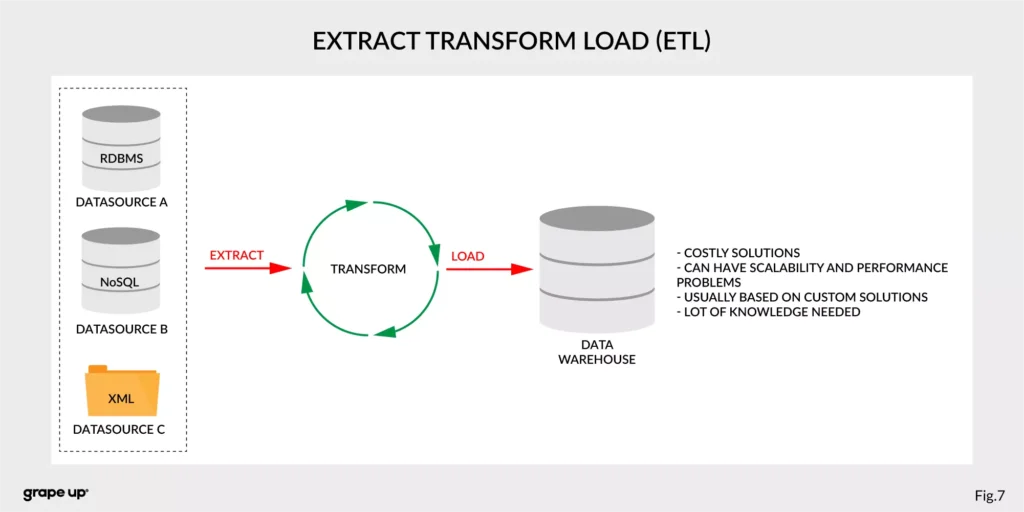

- ETL – Extract, Transform, Load - used to copy data from different sources for analytics/reports.

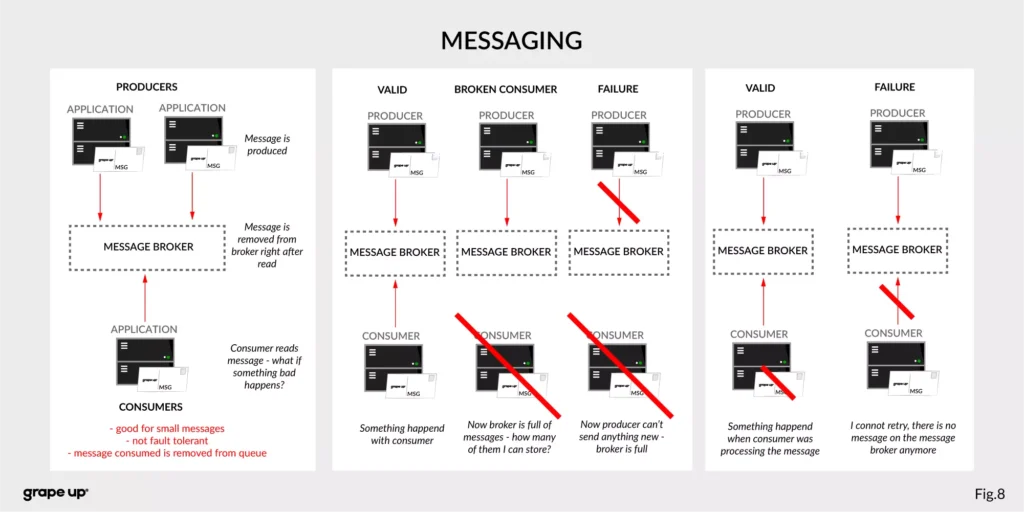

- Messaging systems - provide asynchronous communication between systems.

As you can see, we have a lot of problems that we need to take care of to provide correct data flow across an enterprise organization. That is why Apache Kafka was invented. One more time we have to go to the definition of Apache Kafka. It is called a distributed event streaming platform. Now we know what the event is and how event-driven style looks like. So as you probably can guess, event streaming, in our case, means capturing, storing, manipulating, processing, reacting, and routing event streams in real-time. It is based on three main capabilities – publishing/subscribing, storing, and processing. These three capabilities make this tool very successful.

- Publishing/Subscribing provides an ability to read/write to streams of events and even more – you can continuously import/export data from different sources/systems.

- Storing is also very important here. It solves the abovementioned problems in messaging. You can store streams of events for as long as you want without being afraid that something will be gone.

- Processing allows us to process streams in real-time or use history to process them.

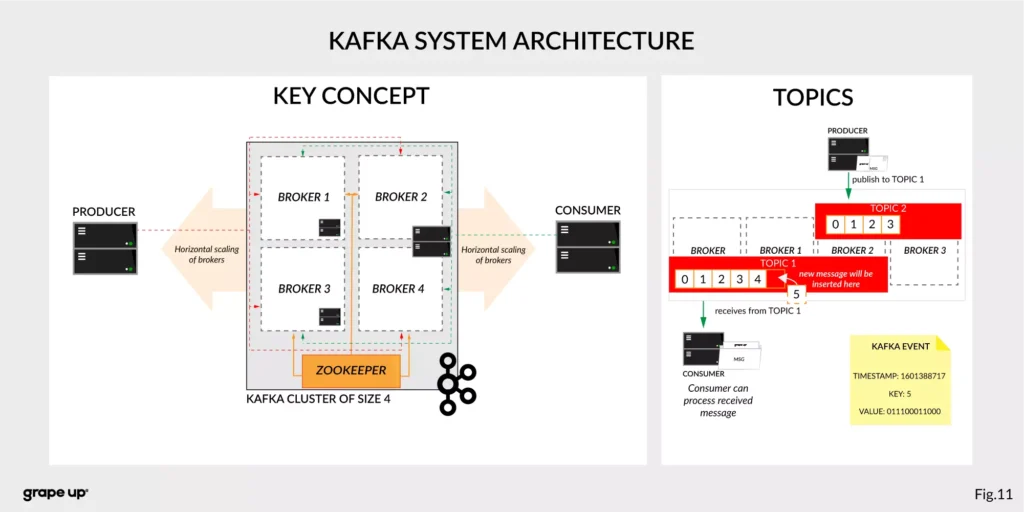

But wait! There is one more word to explain – distributed. Kafka system internally consists of servers and clients. It uses a high-performance TCP Protocol to provide reliable communication between them. Kafka runs as a cluster on one or multiple servers which can be easily deployed in the cloud or on-prem in single or multiple regions. There are also Kafka Connect servers used for integration with other data sources and other Kafka Clusters. Clients that can be implemented in many programming languages have a special role to read/write and process event streams. The whole ecosystem of Kafka is distributed and of course like every distributed system has a lot of challenges regarding node failures, data loss, and coordination.

What are the basic elements of Apache Kafka?

To understand how Apache Kafka works let first explain the basic elements of the Kafka ecosystem.

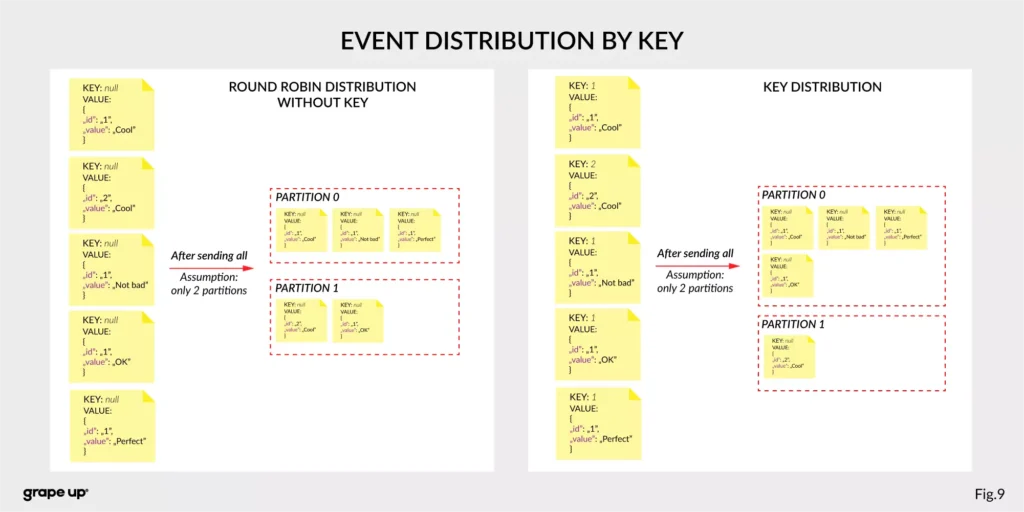

Firstly, we should take a look at the event. It has a key, value, timestamp, and optional metadata headers. A key is used not only for identification, but it is used also for routing and aggregation operations for events with the same key.

As you can see in the figure below - if the message has no key attached, then data is sent using a round-robin algorithm. The situation is different when the event has a key attached. Then the events always go to the partition which holds this key. It makes sense from the performance perspective. We usually use ids to get information about objects, and in that case, it is faster to get it from the same broker than to look for it on many brokers.

The value, as you can guess, stores the essence of the event. It contains information about the business change that happened in the system.

There are different types of events:

- Unkeyed Event – event in which there is no need to use a key. It describes a single fact of what happened in the system. It could be used for metric purposes.

- Entity Event – the most important one. It describes the state of the business object at a given point in time. It must have a unique key, which usually is related to the id of the business object. They are playing the main role in event-driven architectures.

- Keyed Event – an event with a key but not related to any business entity. The key is used for aggregation and partitioning.

Topics –storage for events. The analogy to a folder in a filesystem, where the topic is like a folder that organizes what is inside. An example name of the topic, which keeps all orders events in the e-commerce system can be “ orders” . Unlike in other messaging systems, the events stay on the topic after reading. It makes it very powerful and fault-tolerant. It also solves a problem when the consumer will process something with an error and would like to process it again. Topics can always have zero, single, and multiple producers and subscribers.

They are divided into smaller parts called partitions. A partition can be described as a “commit log”. Messages can be appended to the log and can be read only in the order from the beginning to the end. Partitions are designed to provide redundancy and scalability. The most important fact is that partitions can be hosted on different servers (brokers), and that gives a very powerful way to scale topics horizontally.

Producer – client application responsible for the creation of new events on Kafka Topic. The producer is responsible for choosing the topic partition. By default, as we mentioned earlier round-robin is used when we do not provide any key. There is also a way of creating custom business mapping rules to assign a partition to the message.

Consumer – client application responsible for reading and processing events from Kafka. All events are being read by a consumer in the order in which they were produced. Each consumer also can subscribe to more than one topic. Each message on the partition has a unique integer identifier ( offset ) generated by Apache Kafka which is increased when a new message arrives. It is used by the consumer to know from where to start reading new messages. To sum up the topic, partition and offset are used to precisely localize the message in the Apache Kafka system. Managing an offset is the main responsibility for each consumer.

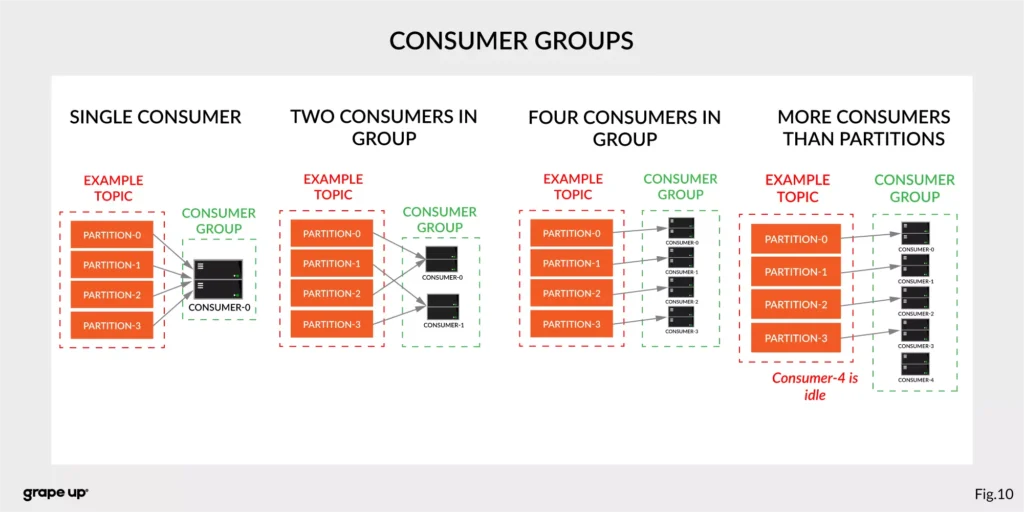

The concept of consumers is easy. But what about the scaling? What if we have many consumers, but we would like to read the message only once? That is why the concept of consumer group was designed. The idea here is when consumer belongs to the same group, it will have some subset of partitions assigned to read a message. That helps to avoid the situation of duplicated reads. In the figure below, there is an example of how we can scale data consumption from the topic. When a consumer is making time-consuming operations, we can connect other consumers to the group, which helps to process faster all new events on the consumer level. We have to be careful though when we have a too-small number of partitions, we would not be able to scale it up. It means if we have more consumers than partitions, they are idle.

But you can ask – what will happen when we add a new consumer to the existing and running group? The process of switching ownership from one consumer to another is called “rebalance.” It is a small break from receiving messages for the whole group. The idea of choosing which partition goes to which consumer is based on the coordinator election problem.

Broker – is responsible for receiving and storing produced events on disk, and it allows consumers to fetch messages by a topic, partition, and offset. Brokers are usually located in many places and joined in a cluster . See the figure below.

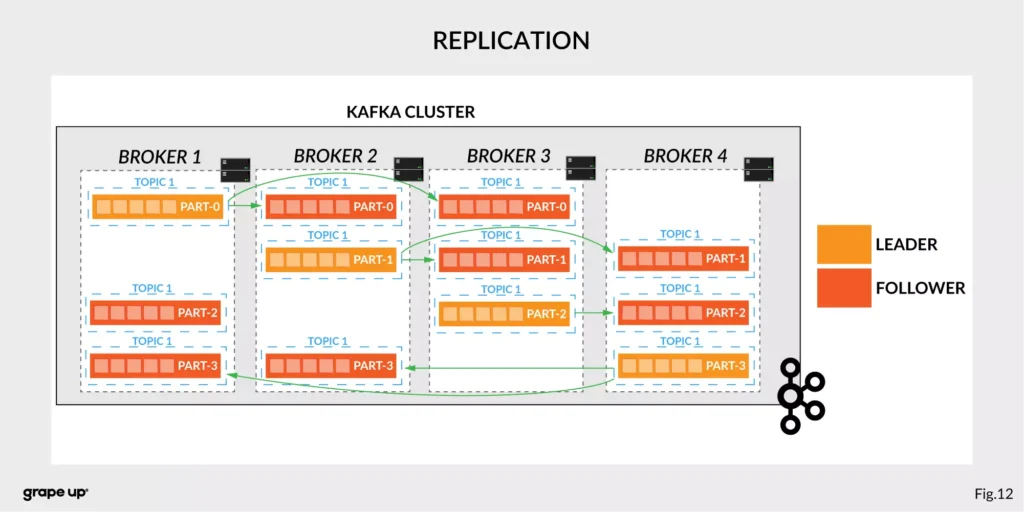

Like in every distributed system, when we use brokers we need to have some coordination. Brokers, as you can see, can be run on different servers (also it is possible to run many on a single server). It provides additional complexity. Each broker contains information about partitions that it owns. To be secure, Apache Kafka introduced a dedicated replication for partitions in case of failures or maintenance. The information about how many replicas do we need for a topic can be set for every topic separately. It gives a lot of flexibility. In the figure below, the basic configuration of replication is shown. The replication is based on the leader-follower approach.

Everything is great! We have found all advantages of using Kafka in comparison to more traditional approaches. Now it is time to say something when to use it.

When to use Apache Kafka?

Apache Kafka provides a lot of use cases. It is widely used in many companies, like Uber, Netflix, Activision, Spotify, Slack, Pinterest, Coursera, LinkedIn, etc. We can use it as a:

- Messaging system – it can be a good alternative to the existing messaging systems. It has a lot of flexibility in configuration, better throughput, and low end-to-end latency.

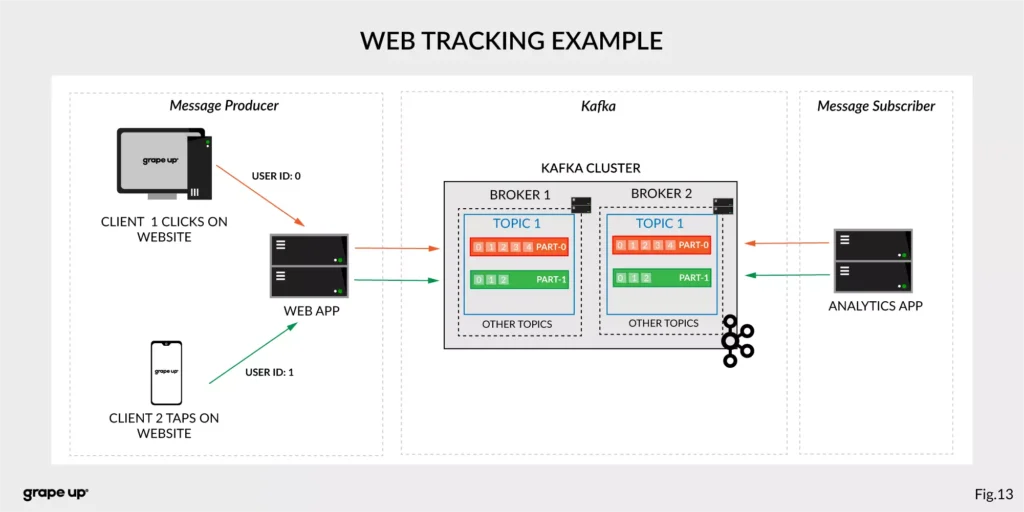

- Website Activity tracking – it was the original use case for Kafka. Activity tracking on the website generates a high volume of data that we have to process. Kafka provides real-time processing for event-streams, which can be sometimes crucial for the business.

Figure 13 presents a simple use case for web tracking. The web application has a button that generates an event after each click. It is used for real-time analytics. Clients' events that are gathered on TOPIC 1. Partitioning is using user-id so client 1 events (user-id = 0) are stored in partition 0 and client 2 (user-id = 1) are stored in partition 1. The record is appended and offset is incremented on a topic. Now, a subscriber can read a message, and present new data on a dashboard or even use older offset to show some statistics.

- Log aggregation – it can be used as an alternative to existing log aggregation solutions. It gives a cleaner way of organizing logs in form of the event streams and what is more, gives a very easy and flexible way to gather logs from many different sources. Comparing to other tools is very fast, durable, and has low end-to-end latency.

- Stream processing – is a very flexible way of processing data using data pipelines. Many users are aggregating, enriching, and transforming data into new topics. It is a very quick and convenient way to process all data in real-time.

- Event sourcing – is a system design in which immutable events are stored as a single source of truth about the system. A typical use case for event sourcing can be found in bank systems when we are loading the history of transactions. The transaction is represented by an immutable event which contains all data describing what exactly happened in our account.

- Commit log – it can be used as an external commit-log for distributed systems. It has a lot of mechanisms that are useful in this use case (like log-compaction, replication, etc.)

Summary

Apache Kafka is a powerful tool used by leading tech enterprises. It offers a lot of use cases, so if we want to use a reliable and durable tool for our data, we should consider Kafka. It provides a loose coupling between producers and subscribers, making our enterprise architecture clean and open to changes. We hope you enjoyed this basic introduction to Apache Kafka and you will try to dig deeper into how it works after this article.

Looking for guidance on implementing Kafka or other event-driven solutions?

Get in touch with us to discuss how we can help.

Sources:

- kafka.apache.org/intro

- confluent.io/blog/journey-to-event-driven-part-1-why-event-first-thinking-changes-everything/

- hackernoon.com/by-2020-50-of-managed-apis-projected-to-be-event-driven-88f7041ea6d8

- ably.io/blog/the-realtime-api-family/

- confluent.io/blog/changing-face-etl/

- infoq.com/articles/democratizing-stream-processing-kafka-ksql-part2/

- cqrs.nu/Faq

- medium.com/analytics-vidhya/apache-kafka-use-cases-e2e52b892fe1

- confluent.io/blog/transactions-apache-kafka/

- martinfowler.com/articles/201701-event-driven.html

- pluralsight.com/courses/apache-kafka-getting-started#

- jaceklaskowski.gitbooks.io/apache-kafka/content/kafka-brokers.html

Bellemare, Adam. Building event-driven microservices: leveraging distributed large-scale data . O'Reilly Media, 2020.

Narkhede, Neha, et al. Kafka: the Definitive Guide: Real-Time Data and Stream Processing at Scale . O'Reilly Media, 2017.

Stopford, Ben. Designing Event-Driven Systems, Concepts and Patterns for Streaming Services with Apache Kafka , O'Reilly Media, 2018.

How to build real-time notification service using Server-Sent Events (SSE)

Most of the communication on the Internet comes directly from the clients to the servers. The client usually sends a request, and the server responds to that request. It is known as a client-server model, and it works well in most cases. However, there are some scenarios in which the server needs to send messages to the clients. In such cases, we have a couple of options: we can use short and long polling, webhooks, websockets, or event streaming platforms like Kafka. However, there is another technology, not popularized enough, which in many cases, is just perfect for the job. This technology is the Server-Sent Events (SSE) standard.

Learn more about services provided by Grape Up

You are at Grape Up blog, where our experts share their expertise gathered in projects delivered for top enterprises. See how we work.

Enabling the automotive industry to build software-defined vehicles

Empowering insurers to create insurance telematics platforms

Providing AI & advanced analytics consulting

What are Server-Sent Events?

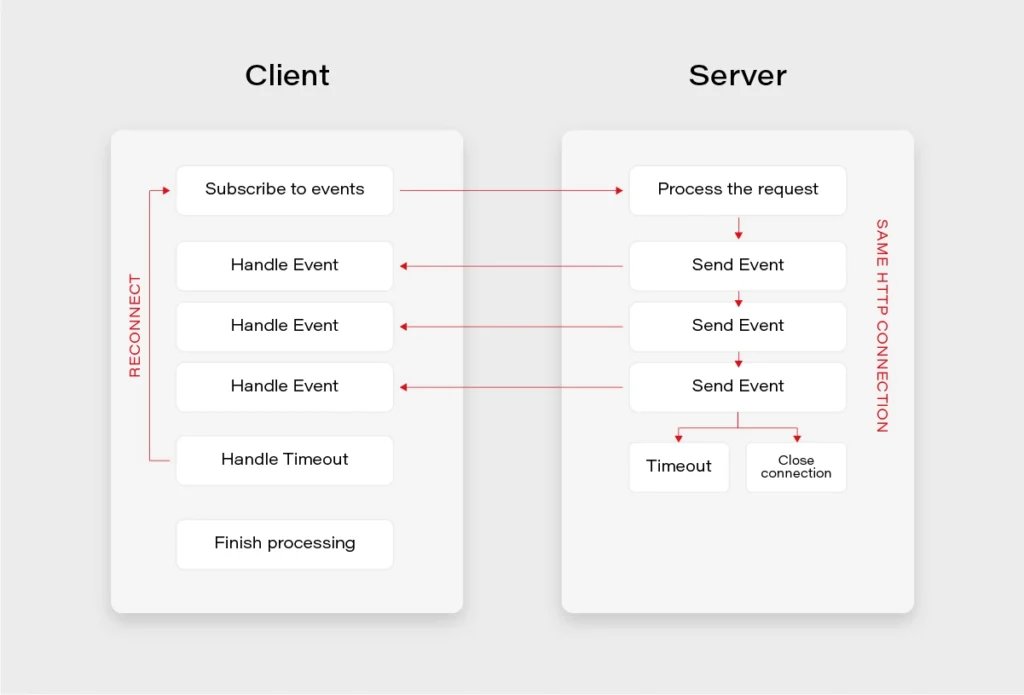

SSE definition states that it is an http standard that allows a web application to handle a unidirectional event stream and receive updates whenever the server emits data. In simple terms, it is a mechanism for unidirectional event streaming.

Browsers support

It is currently supported by all major browsers except Internet Explorer.

Message format

The events are just a stream of UTF-8 encoded text data in a format defined by the Specification. The important aspect here is that the format defines the fields that the SSE message should have, but it does not mandate a specific type for the payload, leaving the freedom of choice to the users.

{

"id": "message id <optional>",

"event": "event type <optional>",

"data": "event data –plain text, JSON, XML… <mandatory>"

}

SSE Implementation

For the SSE to work, the server needs to tell the client that the response’s content-type is text/eventstream . Next, the server receives a regular HTTP request, and leaves the HTTP connection open until no more events are left or until the timeout occurs. If the timeout occurs before the client receives all the events it expects, it can use the built-in reconnection mechanism to reestablish the connection.

Simple endpoint (Flux):

The simplest implementation of the SSE endpoint in Spring can be achieved by:

- Specifying the produced media type as text/event-stream,

- Returning Flux type, which is a reactive representation of a stream of events in Java.

@GetMapping(path = "/stream-flux", produces = MediaType.TEXT_EVENT_STREAM_VALUE)

public Flux<String> streamFlux() {

return Flux.interval(Duration.ofSeconds(1))

.map(sequence -> "Flux - " + LocalTime.now().toString());

ServerSentEvent class:

Spring introduced support for SSE specification in version 4.2 together with a ServerSentEvent class. The benefit here is that we can skip the text/event-stream media type explicit specification, as well as we can add metadata such as id or event type.

@GetMapping("/sse-flux-2")

public Flux<ServerSentEvent> sseFlux2() {

return Flux.interval(Duration.ofSeconds(1))

.map(sequence -> ServerSentEvent.builder()

.id(String.valueOf(sequence))

.event("EVENT_TYPE")

.data("SSE - " + LocalTime.now().toString())

.build());

}

SseEmitter class:

However, the full power of SSE comes with the SseEmitter class. It allows for asynchronous processing and publishing of the events from other threads. What is more, it is possible to store the reference to SseEmitter and retrieve it on subsequent client calls. This provides a huge potential for building powerful notification scenarios.

@GetMapping("/sse-emitter")

public SseEmitter sseEmitter() {

SseEmitter emitter = new SseEmitter();

Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor().execute(() -> {

try {

for (int i = 0; true; i++) {

SseEmitter.SseEventBuilder event = SseEmitter.event()

.id(String.valueOf(i))

.name("SSE_EMITTER_EVENT")

.data("SSE EMITTER - " + LocalTime.now().toString());

emitter.send(event);

Thread.sleep(1000);

}

} catch (Exception ex) {

emitter.completeWithError(ex);

}

});

return emitter;

}

Client example:

Here is a basic SSE client example written in Javascript. It simply defines an EventSource and subscribes to the message event stream in two different ways.

// Declare an EventSource

const eventSource = new EventSource('http://some.url');

// Handler for events without an event type specified

eventSource.onmessage = (e) => {

// Do something - event data etc will be in e.data

};

// Handler for events of type 'eventType' only

eventSource.addEventListener('eventType', (e) => {

// Do something - event data will be in e.data,

// message will be of type 'eventType'

});

SSE vs. Websockets

When it comes to SSE, it is often compared to Websockets due to usage similarities between both of the technologies.

- Both are capable of pushing data to the client,

- Websockets are bidirectional – SSE unidirectional,

- In practice, everything that can be done with SSE, and can also be achieved with Websockets,

- SSE can be easier,

- SSE is transported over a simple HTTP connection,

- Websockets require full duplex-connection and servers to handle the protocol,

- Some enterprise firewalls with packet inspection have trouble dealing with Websockets – for SSE that’s not the case,

- SSE has a variety of features that Websockets lack by design, e.g., automatic reconnection, event ids,

- Only Websockets can send both binary and UTF-8 data, SSE is limited to UTF-8,

- SSE suffers from a limitation to the maximum number of open connections (6 per browser + domain). The issue was marked as Won’t fix in Chrome and Firefox.

Use Cases:

Notification Service Example:

A controller providing a subscribe to events and a publish events endpoints.

@Slf4j

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/events")

@RequiredArgsConstructor

public class EventController {

public static final String MEMBER_ID_HEADER = "MemberId";

private final EmitterService emitterService;

private final NotificationService notificationService;

@GetMapping

public SseEmitter subscribeToEvents(@RequestHeader(name = MEMBER_ID_HEADER) String memberId) {

log.debug("Subscribing member with id {}", memberId);

return emitterService.createEmitter(memberId);

}

@PostMapping

@ResponseStatus(HttpStatus.ACCEPTED)

public void publishEvent(@RequestHeader(name = MEMBER_ID_HEADER) String memberId, @RequestBody EventDto event) {

log.debug("Publishing event {} for member with id {}", event, memberId);

notificationService.sendNotification(memberId, event);

}

}

A service for sending the events:

@Service

@Primary

@AllArgsConstructor

@Slf4j

public class SseNotificationService implements NotificationService {

private final EmitterRepository emitterRepository;

private final EventMapper eventMapper;

@Override

public void sendNotification(String memberId, EventDto event) {

if (event == null) {

log.debug("No server event to send to device.");

return;

}

doSendNotification(memberId, event);

}

private void doSendNotification(String memberId, EventDto event) {

emitterRepository.get(memberId).ifPresentOrElse(sseEmitter -> {

try {

log.debug("Sending event: {} for member: {}", event, memberId);

sseEmitter.send(eventMapper.toSseEventBuilder(event));

} catch (IOException | IllegalStateException e) {

log.debug("Error while sending event: {} for member: {} - exception: {}", event, memberId, e);

emitterRepository.remove(memberId);

}

}, () -> log.debug("No emitter for member {}", memberId));

}

}

To sum up, Server-Sent Events standard is a great technology when it comes to a unidirectional stream of data and often can save us a lot of trouble compared to more complex approaches such as Websockets or distributed streaming platforms.

A full notification service example implemented with the use of Server-Sent Events can be found on my github: https://github.com/mkapiczy/server-sent-events

If you're looking to build a scalable, real-time notification system or need expert guidance on modern software solutions, Grape Up can help . Our engineering teams help enterprises design, develop, and optimize their software infrastructure.

Get in touch to discuss your project and see how we can support your business.

Sources:

- https://www.baeldung.com/spring-server-sent-events

- https://www.w3.org/TR/eventsource/

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/5195452/websockets-vs-server-sent-events-eventsource

- https://www.telerik.com/blogs/websockets-vs-server-sent-events

- https://simonprickett.dev/a-look-at-server-sent-events/

How to build hypermedia API with Spring HATEOAS

Have you ever considered the quality of your REST API? Do you know that there are several levels of REST API? Have you ever heard the term HATEOAS? Or maybe you wonder how to implement it in Java? In this article, we answer these questions with the main emphasis on the HATEOAS concept and the implementation of that concept with the Spring HATEOAS project.

Learn more about services provided by Grape Up

You are at Grape Up blog, where our experts share their expertise gathered in projects delivered for top enterprises. See how we work.

Enabling the automotive industry to build software-defined vehicles

Empowering insurers to create insurance telematics platforms

Providing AI & advanced analytics consulting

What is HATEOAS?

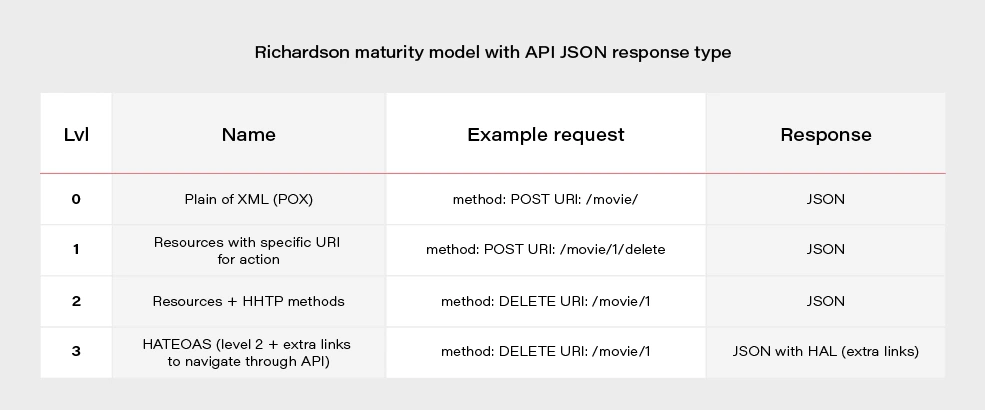

H ypermedia A s T he E ngine O f A pplication S tate - is one of the constraints of the REST architecture. Neither REST nor HATEOAS is any requirement or specification. How you implement it depends only on you. At this point, you may ask yourself - how RESTful your API is without using HATEOAS? This question is answered by the REST maturity model presented by Leonard Richardson. This model consists of four levels, as set out below:

- Level 0

The API implementation uses the HTTP protocol but does not utilize its full capabilities. Additionally, unique addresses for resources are not provided. - Level 1

We have a unique identifier for the resource, but each action on the resource has its own URL. - Level 2

We use HTTP methods instead of verbs describing actions, e.g., DELETE method instead of URL .../delete - Level 3

The term HATEOAS has been introduced. Simply speaking, it introduces hypermedia to resources. That allows you to place links in the response informing about possible actions, thereby adding the possibility to navigate through API.

Most projects these days are written using level 2. If we would like to go for the perfect RESTful API, we should consider HATEOAS.

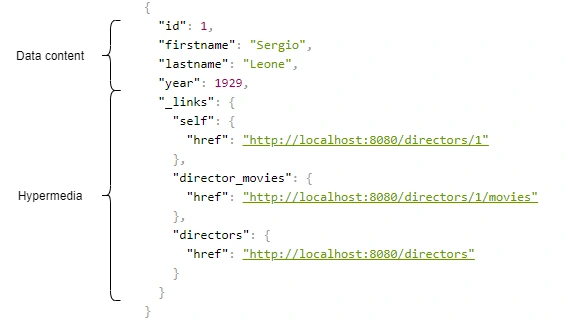

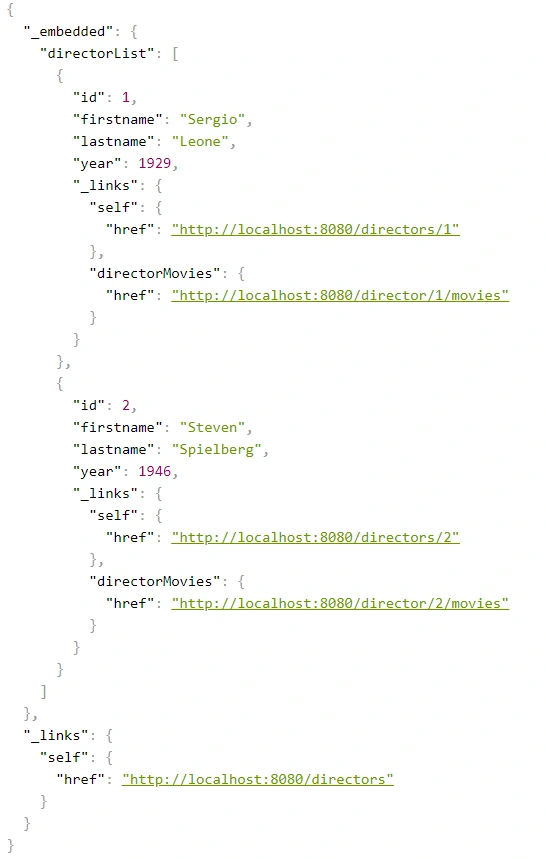

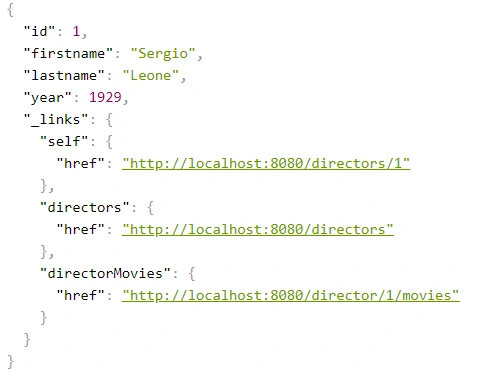

Above, we have an example of a response from the server in the form of JSON+HAL. Such a resource consists of two parts: our data and links to actions that are possible to be performed on a given resource.

Spring HATEOAS 1.x.x

You may be asking yourself how to implement HATEOAS in Java? You can write your solution, but why reinvent the wheel? The right tool for this seems to be the Spring Hateoas project. It is a long-standing solution on the market because its origins date back to 2012, but in 2019 we had a version 1.0 release. Of course, this version introduced a few changes compared to 0.x. They will be discussed at the end of the article after presenting some examples of using this library so that you better understand what the differences between the two versions are. Let’s discuss the possibilities of the library based on a simple API that returns us a list of movies and related directors. Our domain looks like this:

@Entity

public class Movie {

@Id

@GeneratedValue

private Long id;

private String title;

private int year;

private Rating rating;

@ManyToOne

private Director director;

}

@Entity

public class Director {

@Id

@GeneratedValue

@Getter

private Long id;

@Getter

private String firstname;

@Getter

private String lastname;

@Getter

private int year;

@OneToMany(mappedBy = "director")

private Set<Movie> movies;

}

We can approach the implementation of HATEOAS in several ways. Three methods represented here are ranked from least to most recommended.

But first, we need to add some dependencies to our Spring Boot project:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-hateoas</artifactId>

</dependency>

Ok, now we can consider implementation options.

Entity extends RepresentationModel with links directly in Controller class

Firstly, extend our entity models with RepresentationModel.

public class Movie extends RepresentationModel<Movie>

public class Director extends RepresentationModel<Director>

Then, add links to RepresentationModel within each controller. The example below returns all directors from the system. By adding two links to each director - to himself and to the entire collection. A link is also added to the collection. The key elements of this code are two methods with static imports:

-

linkTo() -

methodOn()

@GetMapping("/directors")

public ResponseEntity<CollectionModel<Director>> getAllDirectors() {

List<Director> directors = directorService.getAllDirectors();

directors.forEach(director -> {

director.add(linkTo(methodOn(DirectorController.class).getDirectorById(director.getId())).withSelfRel());

director.add(linkTo(methodOn(DirectorController.class).getDirectorMovies(director.getId())).withRel("directorMovies"));

});