Capturing objects in closures: Why you’re doing it wrong? – Part 2

Choose your closure context wisely

In the first part of this article , we defined several simple principles of capturing objects in Closures. According to these principles, the closure code associated with a particular instance of a certain type should be considered separately from the code, which is associated either with the global scope or with the type itself. We also came to the conclusion that the pattern with “weakifying” self and “strongifying” inside the closure should be limited to the code which really depends on self while the other code should be executed independently. But let’s take a closer look at such instance-dependent code. The following proves that the situation is not so obvious.

func uploadFile(url: URL, completion: @escaping (Error?) -> Void) {

// Getting file content data from URL

//...

// Creating file info

let fileInfoID = self.databaseController.createRecord(data: fileInfo)

self.remoteFileManager.uploadBinaryData(fileContentData) { [weak self] error in

guard let strongSelf = self else {

completion(UploadError.dataError)

return

}

if error != nil {

strongSelf.databaseController.removeRecord(recordID: fileInfoID)

completion(error)

} else {

// Wait while server will make needed changes to file info

strongSelf.startTrackingOnServer(recordID: fileInfoID,

completion: completion)

}

}

}

The code above creates a record in the database that contains the file info and loads the file to the server. If the upload is successful, the method will notify the server that changes to the file info should be made. Otherwise, in case of an error, we should remove the file info from the database. Both actions depend on self , so neither of them can be performed if the object referenced by self had been deallocated before the completion was called. Therefore, calling the completion at the beginning of the closure with the appropriate error in this case seems to be reasonable.

However, such approach breaks the closure logic. If the error occurs, but self was deallocated before the call closure, we would leave the record about the file that hasn’t been uploaded. Hence, capturing a weak reference to self is not completely correct here. However, since it is obvious that we cannot capture self as a strong reference to prevent a retain cycle – what should be done instead in that case?

Let’s try to separate the required actions from the optional ones. An object referenced by self may be deallocated, but we have to remove the record from the database. With that said, we shouldn’t associate the database with the self object, but rather use it separately:

func uploadFile(url: URL, completion: @escaping (Error?) -> Void) {

// Getting file content data from URL

//...

// Creating file info

let fileInfoID = self.databaseController.createRecord(data: fileInfo)

self.databaseController.uploadBinaryData(fileContentData) { [weak self, databaseController] error in

if error != nil {

databaseController.removeRecord(recordID: fileInfoID)

completion(error)

} else if let strongSelf = self {

// Wait while server will make needed changes to file info

strongSelf.startTrackingOnServer(recordID: fileInfoID, completion: completion)

} else {

databaseController.removeRecord(recordID: fileInfoID)

completion(UploadError.dataError)

}

}

}

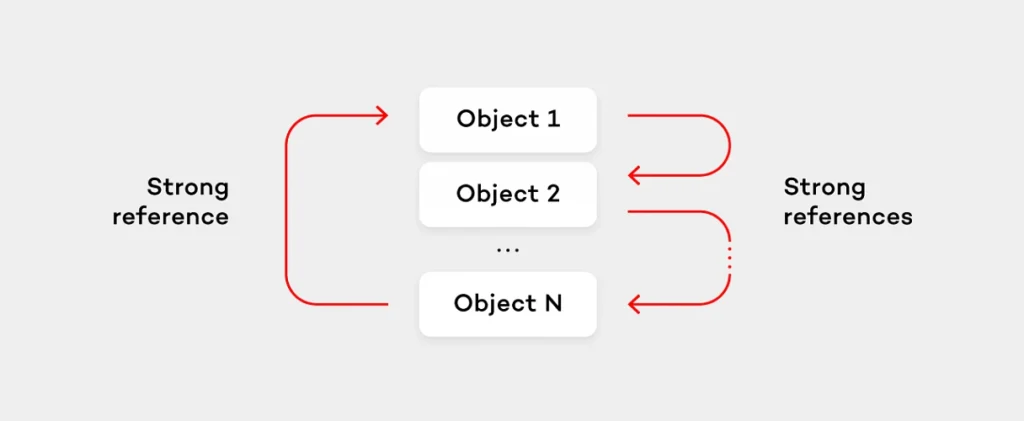

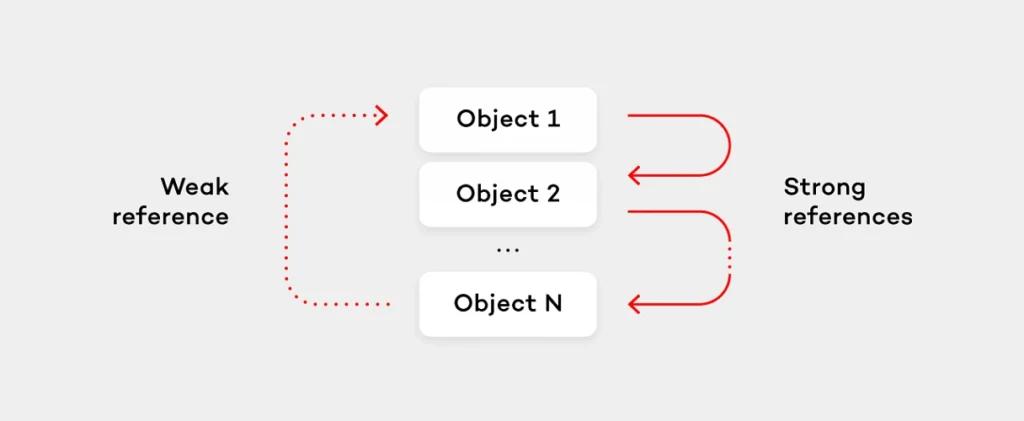

Pay attention to the closure capture list. It is where we explicitly specify the databaseController property. This will create a separate local variable inside the closure with the same name referencing this property. Since we didn’t add any modifier to it, the databaseController is captured by a strong reference. While self is still a weak reference, there won’t be any retain cycle – which is exactly what we need. As a result, the code is now consistent.

We remove the record from the database in case of an error or in case further action cannot be performed because self got deallocated (also treating this case as an error).

So, what is the key difference between this code and the previous one? Previously, we were treating self as the only source of our actions inside the closure. Because of that, the weak reference semantic of self forced all actions to be optional.

By capturing the object as weak reference we’re saying: “Hey, I don’t need to force this object to live until the closure is executed. It may be deallocated before and that’s fine for me”. However, we forgot about one important thing. Namely, it’s not our real intention to make self optional in the closure. Instead, we had to use weak self reference in order not to produce the retain cycle, while some of our actions are required (removing redundant file info from database in case of an error).

Based on this example, we can draw some important conclusions. Even if the object is associated with self (is its property), we should not treat self as a root object from which we take other objects inside the closure to perform calls on them. Instead, the properties of the self object may be captured independently if needed.

Let’s take a look at a more generic, yet clear example.

func uploadFile(url: URL, completion: @escaping (Error?) -> Void) {

// Some preparations

// ...

self.someAsyncAction(parameter) { [weak self] in

guard let strongSelf = self else {

return

}

// ...

// These calls should be performed

strongSelf.someObject.requiredToBeCalled()

strongSelf.someObject.requiredValue = someValue

// While these ones have sense only if self object still exists

strongSelf.otherObject.mayBeCalled()

strongSelf.otherObject.someOptionalValue = someOtherValue

// currentItem represents selected object that is required to be updated

// on closure call. Selection may be change several times before our

// asynchronous action completion

strongSelf.anotherObject.currentItem.someProperty.requiredUpdate()

}

}

According to what we’ve just learned, self should not be used in such way for all calls. Therefore, let’s make some corrections to our code. In this example some calls are required and some are optional. We can safely use self for all optional calls. For each required one we should determine which object needs to be captured by a strong reference from the call chain like the following: strongSelf.oject0.object1...objectN.action() . For the first two calls such principle object is obviously the someObject property. The first one is a call of requiredToBeCalled() method on it.

The second one assigns value to its requiredValue property. Consequently, instead of getting it as a property of self , we should directly capture someObject in the closure. The next two lines manipulate with the otherObject property.

As seen in our example, these calls are optional. Meaning, they may be omitted if the object pointed by self is deallocated (they don’t make sense without self ). The last line is a bit trickier. It has several properties in a call chain. Since the object on which the call is performed is represented by someProperty , we may want to capture it directly. However, the actual value returned by anotherObject.currentItem may (by definition) change. That is, the call to self.anotherObject.currentItem inside the closure may return a different object from the one it was returning before someAsyncAction() was called.

Thus, in case of capturing someProperty , we may potentially use an object which is out of date and is returned by some old currentItem , while the actual one will remain unchanged. Of course, for the same reason we should not capture the currentItem object itself. So, the right choice here is the anotherObject property which is the source of the actual currentItem object. After rewriting the example according to our corrections, we will receive the following:

func uploadFile(url: URL, completion: @escaping (Error?) -> Void) {

// Some preparations

// ...

self.someAsyncAction(parameter) { [weak self, someObject, anotherObject] in

// ...

// These calls should be performed

someObject.requiredToBeCalled()

someObject.requiredValue = someValue

// While these ones have sense only if self object still exists

if let strongSelf = self {

strongSelf.otherObject.mayBeCalled()

strongSelf.otherObject.someOptionalValue = someOtherValue

}

// currentItem represents selected object that is required to be updated

// on closure call. Selection may be change several times before our

// asynchronous action completion

anotherObject.currentItem.someProperty.requiredUpdate()

}

}

In general, when we have a call chain as follows self.oject0.object1...objectN.action() to determine which object from the chain should be captured, we should find objectK that conforms to the following rule:

There are two ways of calling our action() inside our closure:

1. Capture self and use it as a root (or source) object (full call chain).

2. Using objectK in closure directly (call subchain) should have exactly the same effect.

That is, if we were to substitute the call chain self.oject0.object1...objectK...objectN.action() (capturing self ) in the closure with the subchain objectK...objectN.action() (capturing objects pointed by objectK at the moment of the closure definition) the effect of the call will be the same. In case there are several objects conforming to this rule, it’s better to choose the one that is the closest to the action (method call or property change). This will avoid redundant dependencies in the closure. For example, if in the call chain self.object0.object1.object2.object3.action() we have object0, object1, object2 conforming to the rule, it’s better to use object2.object3.action() in closure rather than object0.object1.object2.object3.action() since the longest chain means more semantic dependencies - the source of our action will be object0 from which we get the next object1 and so on instead of using object2 directly).

Bring it all together

Let’s now summarize our knowledge about the closure context. In cases where retain cycles may occur, we should be very careful with what we capture inside the closure. We should definitely not use the “weakify” - ”strongify” pattern in all cases as a rule of thumb. There is no “golden rule” here. Instead, we have a set of principles for writing the closure code that we should follow not only to resolve a retain cycle problem, but also to keep the closure implementation consistent. These are the following:

1. Determine the instance that can cause a retain cycle ( self or any other object the capturing of which can cause a retain cycle).

2. The code that is not related to this particular instance should be considered. Such code may perform actions on other objects or even types (including the type of our instance ). Therefore, the code should be executed regardless of whether the instance exists inside the closure or not.

3. For the code which relates to the instance we should define which part of it is optional (may be omitted if instance is deallocated) and which part is required (should be called independently of instance existence).

4. For the optional code we may apply the “weakify” - ”strongify” pattern to the instance . That way, we’ll try to obtain a strong reference to that instance inside the closure using captured weak reference. And we’ll perform optional actions only if it still exists.

5. For performing required code we cannot apply reference to the instance . Instead, for each call chain like instance.property0.property1...propertyN.requiredAction() we need to define what property to use for capturing the corresponding object in the closure. In most cases, however, it’s simple. For instance, in the example mentioned earlier for self.someObject.requiredToBeCalled() call we choose someObject to be captured.

Please note that the proposed solution isn’t only limited to capturing self in closures. The principles listed above may be applied to any object that may cause a retain cycle inside the closure.

But let’s point out that we’re not defining strict rules. There are no such rules when it comes to closure context. What we’ve done here is we deduced some principles based on common use cases of closures. There may be other, much more complicated examples in real code. Sometimes it’s really challenging to choose what objects to retain inside the closure, especially when refactoring existing code. The main goal of this article is to give useful tips on how to deal with the closure context, how to have the right mindset when choosing the objects that should be used inside the closure and a correct reference semantic for them.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.