Cloud-native applications: 5 things you should know before you start

Introduction

Building cloud-native applications has become a direction in IT that has already been followed by companies like Facebook, Netflix or Amazon for years. The trend allows enterprises to develop and deploy apps more efficiently by means of cloud services and provides all sorts of run-time platform capabilities like scalability, performance and security. Thanks to this, developers can actually spend more time delivering functionality and speed up Innovation. What else is there that leaves the competition further behind than introducing new features at a global scale according to customer needs? You either keep up with the pace of the changing world or you don’t. The aim of this article is to present and explain the top 5 elements of cloud-native applications.

Why do you need cloud-native applications in the first place?

It is safe to say that the world we live in has gone digital. We communicate on Facebook, watch movies on Netflix, store our documents on Google Drive and at least a certain percentage of us shop on Amazon. It shouldn’t be a surprise that business demands are on a constant rise when it comes to customer expectations. Enterprises need a high-performance IT organization to be on top of this crowded marketplace.

Throughout the last 20 years the world has witnessed an array of developments in technology as well as people & culture. All these improvements took place in order to start delivering software faster. Automation, continuous integration & delivery to DevOps and microservice architecture patterns also serve that purpose. But still, quite frequently teams have to wait for infrastructure to become available, which significantly slows down the delivery line.

Some try to automate infrastructure provisioning or make an attempt towards DevOps. However, if the delivery of the infrastructure relies on a team that works remotely and can’t keep up with your speed, automated infrastructure provisioning will not be of much help. The recent rise of cloud computing has shown that infrastructure can be made available at a nearly infinite scale. IT departments are able to deliver their own infrastructure just as fast as if they were doing their regular online shopping on Amazon. On top of that, cloud infrastructure is simply cost efficient, as it doesn’t need tons of capital investment in advance. It represents a transparent pay-as-you-go model. Which is exactly why this kind of infrastructure has won its popularity among startups or innovation departments where a solution that tries out new products quickly is a golden ticket. So, what IS there to know before you dive in?

The ingredients of cloud-native apps, and what makes them native?

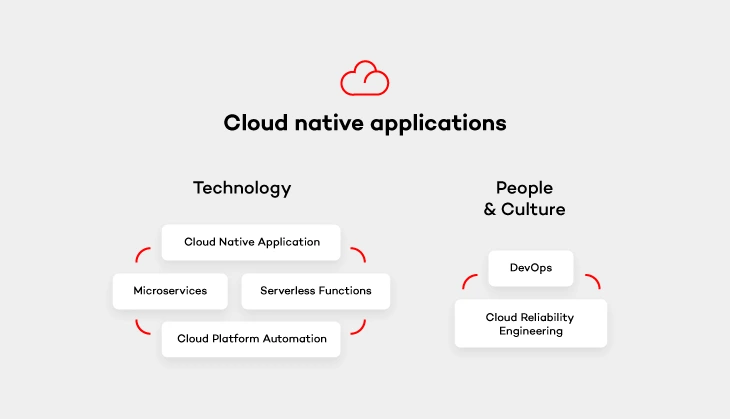

Now that we have explained the need for cloud-native apps, we can still shed a light on the definition, especially because it doesn’t always go hand in hand with its popularity. Cloud native apps are those applications that have been built to live and run in the cloud. If you want to get a better understanding of that it means - I recommend reading on. There are 5 elements divided into 2 categories (excluding the application itself) that are essential for creating cloud native environments.

Cloud platform automation

In other words, the natural habitat in which cloud-native applications live. It provides services that keep the application running, manage security and network. As stated above, the flexibility of such cloud platform and its cost-efficiency thanks to the pay-as-you-go model is perfect for enterprises who don’t want to pay through the nose for infrastructure from the very beginning.

Serverless functions

These small, one-purpose functions that allow you to build asynchronous event-driven architectures by means of microservices. Don’t let the „serverless” part of their name misleads you, though. Your code WILL run on servers. The only difference is that it’s on the cloud provider’s side to handle accelerating instances to run your code and scale out under load. There are plenty of serverless functions out there offered by cloud providers that can be used by cloud-native apps. Services like IoT, Big Data or data storage are built from open-source solutions. It means that you simply don’t have to take care of some complex platform, but rather focus on functionality itself and not have to deal with the pains of installation and configuration.

Microservices architecture pattern

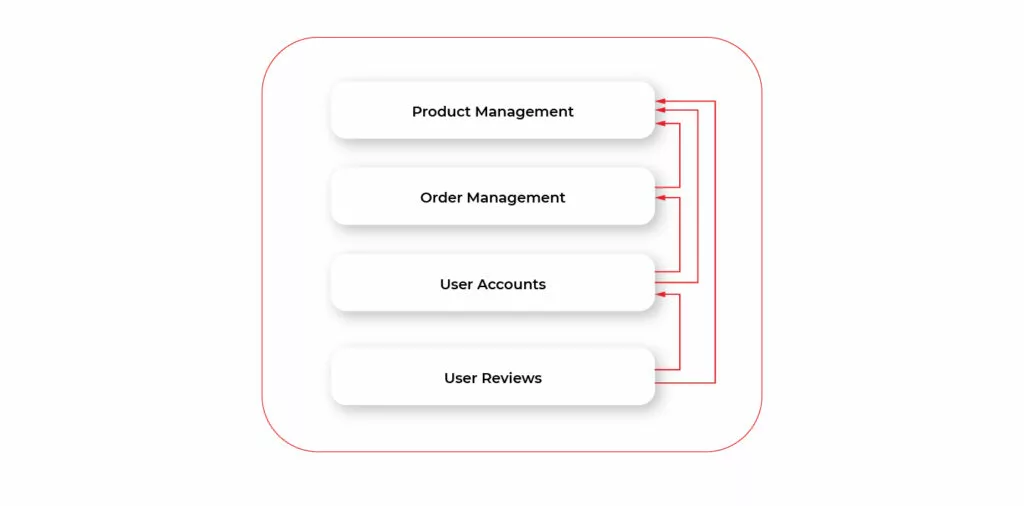

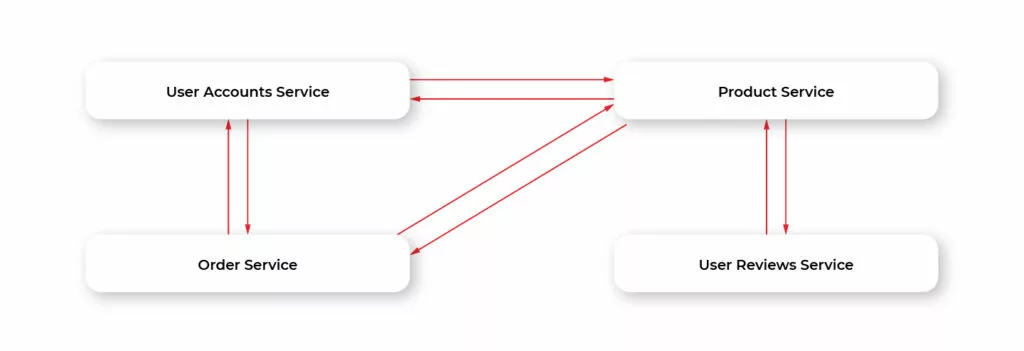

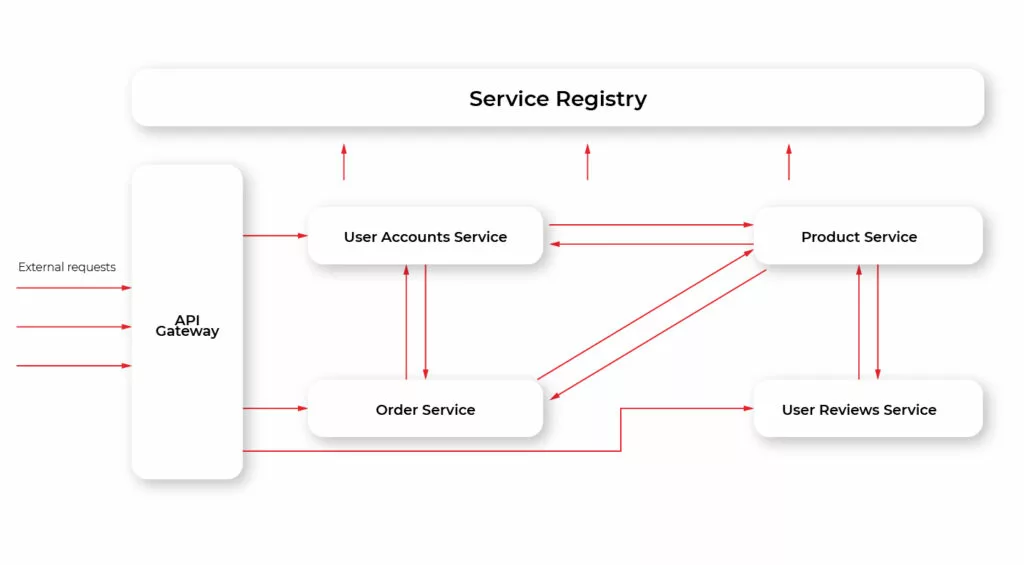

Architecture pattern aims to provide self-contained software products which implement one type of a single-purpose function that can be developed, tested and deployed separately to speed up the product’s time to market. Which is equal to what cloud-native apps offer.

Once you get down to designing microservices, remember to do it in a way so that they can run cloud native. Most likely, you will come across one of the biggest challenges when it comes to the ability to run your app in a distributed environment across application instances. Luckily, there are these 12-factor app design principles which you can follow with a peaceful mind. These principles will help design such microservices that can run cloud native.

DevOps culture

The journey with cloud-native applications comes not only with a change in technology, but also with a culture change. Following DevOps principles is essential for cloud-native apps . Therefore, getting the whole software delivery pipeline to work automatically will only be possible if development and operation teams cooperate closely together. Development engineers are those who are in charge of getting the application to run on the cloud platform. While operations engineers handle development, operations and automation of that platform.

Cloud reliability engineering

And last but not least – cloud reliability engineering that comes from Google’s Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) concept. It is based on approaching the platform administration in the same way as software engineering. As stated by Ben Treynor , VP of Engineering at Google „Fundamentally, it’s what happens when you ask a software engineer to design an operations function (…). So SRE is fundamentally doing work that has historically been done by an operations team, but using engineers with software expertise, and banking on the fact that these engineers are inherently both predisposed to, and have the ability to, substitute automation for human labor.”

Treynor also claims that the roles of many operations teams nowadays are similar. But the way SRE teams work is significantly different because of several reasons. SRE people are software engineers with software development abilities and are characterized by proclivity. They have enough knowledge about programming languages, data structures, algorithms and performance. The result? They can create software that is more effective.

Summary

Cloud- native applications are one of the reasons why big players such as Facebook or Amazon stay ahead of the competition. The article sums up the most important factors that comprise them. Of course, the process of building cloud native apps goes far beyond choosing the tools. The importance of your team (People & Culture) can never be stressed enough. So what are the final thoughts? Advocate DevOps and follow Google’s Cloud Engineering principles to make your company efficient and your platform more reliable. You will be surprised at how fast cloud-native will help your organization become successful.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.