Cloud development overview for non-cloud developers

Introduction

This article covers basic concepts of web applications that are designed to be run in Cloud environment and are intended for software engineers who are not familiar with Cloud Native development but work with other programming concepts/technologies. The article gives an overview of the basics from the perspective of concepts that are already known to non-cloud developers including mobile and desktop software engineers.

Basic concepts

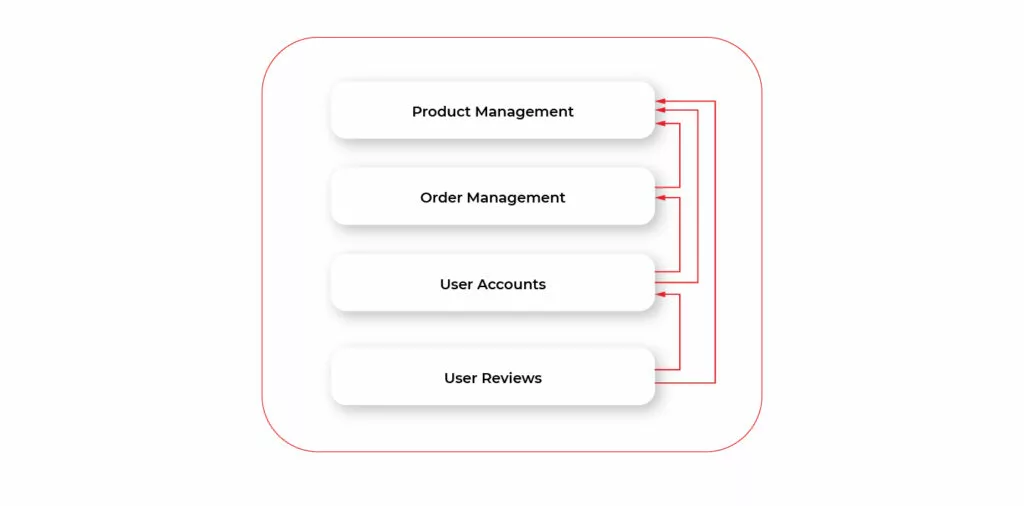

Let’s start with something simple. Let’s imagine that we want to write a web application that allows users to create an account, order the products and write reviews on them. The simplest way is to have our backend app as a single app combining UI and code. Alternatively, we may split it frontend and into the backend, which just provides API.

Let’s focus on the backend part. The whole communication between its components happens inside of a single app, on a code level. From the executable file perspective, our app is a monolithic piece of code: it’s a single file or package. Everything looks simple and clean: the code is split into several logical components, each component has its own layers. The possible overall architecture may look as follows:

But as we try to develop our app we'll quickly figure out that the above approach is not enough in the modern world and modern web environment. To understand what's wrong with the app architecture we need to figure out the key specificity of web apps compared to desktop or mobile apps. Let’s describe quite simple yet very important points. While being obvious to some (even non-web) developers the points are crucial for understanding essential flaws of our app while running in the modern server environment.

Desktop or mobile app runs on the user's device. This means that each user has their own app copy running independently. For web apps, we have the opposite situation. In a simplified way, in order to use our app user connects to a server and utilizes an app instance that runs on that server. So, for web apps, all users are using a single instance of the app. Well, in real-world examples it's not strictly a single instance in most cases because of scaling. But the key point here is that the number of users, in a particular moment of time is way greater than the number of app instances. In consequence, app error or crash has incomparably bigger user impact for web apps. I.e., when a desktop app crashes, only a single user is impacted. Moreover, since the app runs on their device they may just restart the app and continue using it. In case of a web app crash, thousands of users may be impacted. This brings us to two important requirements to consider.

- Reliability and testability

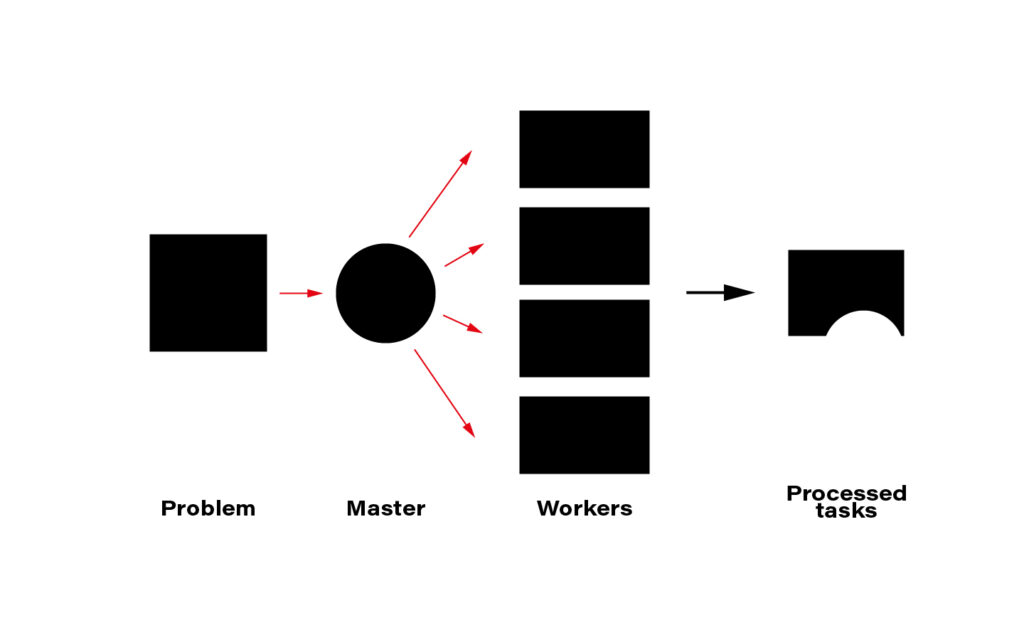

Since all the code is placed in a single (physical) app our changes to one component during development of the new features may impact any other existing app component. Hence, after implementing a single feature we have to retest the whole app. If we have some bug in our new code that leads to a crash, once the app crashes it becomes unavailable to all the users. Before we figure out the crash we have some downtime when users cannot use the app. Moreover to prevent further crashes we have to roll back to a previous app version. And if we delivered some fixes/updates along with the new feature we’ll lose those improvements. - Scalability

Consider the number of users is increased during a short period. In case of our example app, this may happen due to, e.g., discounts or new attractive products coming in. It quickly turns out that one app instance running is not enough. We have too many requests and app “times out” requests it cannot handle. We may just increase the number of running instances of the app. Hence, each instance will independently handle user orders. But after a closer look, it turns out that we actually don’t need to scale the whole app. The only part of the app that needs to handle more requests is creating and storing orders for a particular product. The rest of the app doesn’t need to be scaled. Scaling other components will result in unneeded memory growth. But since all the components are contained in a monolith (single binary) we can only scale all of them at once by launching new instances.

The other thing to consider is network latency which adds important limitations compared to mobile or desktop apps. Even though the UI layer itself runs directly in the browser (javascript), any heavy computation or CRUD operation requires http call. Since such network calls are relatively slow (compared to interactions between components in code) we should optimize the way we work with data and some server-side computations.

Let’s try to address the issues we described above.

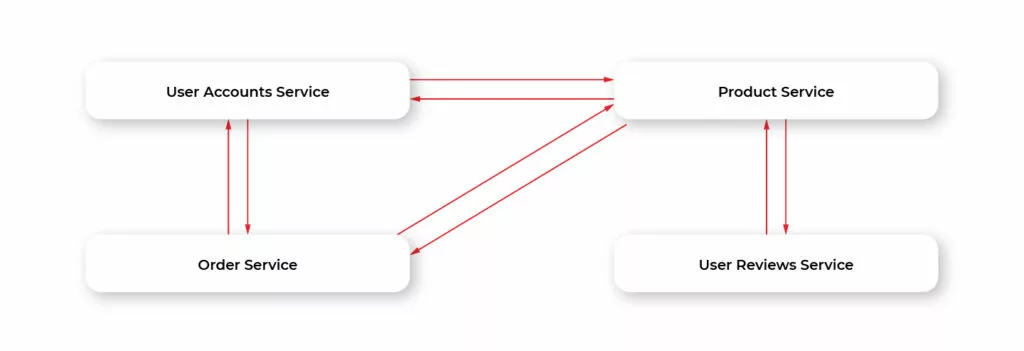

Microservices

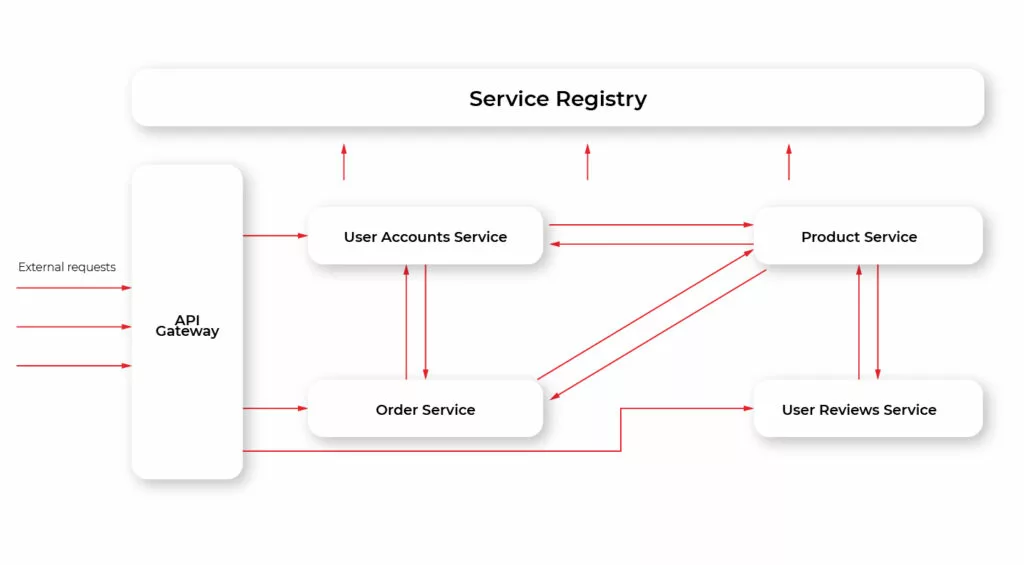

Let’s make a simple step and split our app into a set of smaller apps called microservices. The diagram below illustrates the general architecture of our app rethinks using microservices.

This helps us solve the problems of monolithic apps and has some additional advantages.

• Implementing a new feature (component) results in adding a new service or modifying the existing one. This reduces the complexity of the development and increases testability. If we have a critical bug we will simply disable that service while the other app parts will still work (excluding the parts that require interaction with the disabled service) and contain any other changes/fixes not related to the new feature.

• When we need to scale the app we may do it only for a particular component. E.g., if a number of purchases increase we may increment the number of running instances of Order Service without touching other ones.

• Developers in a team can work fully independently while developing separate microservices. We’re also not limited by a single language. Each microservice may be written in a different language.

• Deployment becomes easier. We may update and deploy each microservice independently. Moreover, we can use different server/cloud environments for different microservices. Each service can use its own third-party dependency services like a database or message broker.

Besides its advantages, microservice architecture brings additional complexity that is driven by the nature of microservice per se: instead of a single big app, we now have multiple small applications that have to communicate with each other through a network environment.

In terms of desktop apps, we may bring up here the example of inter-process communication, or IPC. Imagine that a desktop app is split into several smaller apps, running independently on our machine. Instead of calling methods of different app modules within a single binary we now have multiple binaries. We have to design a protocol of communication between them (e.g., based on OS native IPC API), we have to consider the performance of such communication, and so on. There may be several instances of a single app running at the same time on our machine. So, we should find out a way to determine the location of each app within the host OS.

The described specificity is very similar to what we have with microservices. But instead of running on a single machine microservice apps run in a network which adds even more complexity. On the other hand, we may use already existing solutions, like http for communicating between services (which is how microservices communicate in most cases) and RESTful API on top of it.

The key thing to understand here is that all the basic approaches described below are introduced mainly to solve the complexity resulting from splitting a single app into multiple microservices.

Locating microservices

Each microservice that calls API of another microservice (often called client service) should know its location. In terms of calling REST API using http the location consists of address and port. We can hardcode the location of the callee in the caller configuration files or code. But the problem is that can be instantiated, restarted, or moved independently of each other. So, hardcoding is not a solution as if the callee service location is changed the caller will have to be restarted or even recompiled. Instead, we may use Service Registry pattern.

To put it simply, Service Registry is a separate application that holds a table that maps a service id to its location. Each service is registered in Service Registry on startup and deregistered on shutdown. When client service needs to discover another service it gets the location of that service from the registry. So, in this model, each microservice doesn’t know the concrete location of its callee services but just their ids. Hence, if a certain service changes its location after restart the registry is updated and its client services will be able to get this new location.

Service discovery using a Service registry may be done in two ways.

1. Client-side service discovery. Service gets the location of other services by directly querying the registry. Then calls discovered the service’s API by sending a request to that location. In this case, each service should know the location of the Service Registry. Thus, its address and port should be fixed.

2. Server-side service discovery. Service may send API call requests along with service id to a special service called Router. Router retrieves the actual location of the target service and forwards the request to it. In this case, each service should know the location of the Router.

Communicating with microservices

So, our application consists of microservices that communicate. Each has its own API. The client of our microservices (e.g., frontend or mobile app) should use that API. But such usage becomes complicated even for several microservices. Another example, in terms of desktop interprocess communication, imagines a set of service apps/daemons that manage the file system. Some may run constantly in the background, some may be launched when needed. Instead of knowing details related to each service, e.g., functionality/interface, the purpose of each service, whether or not it runs, we may use a single facade daemon, that will have a consistent interface for file system management and will internally know which service to call.

Referring back to our example with the e-shop app consider a mobile app that wants to use its API. We have 5 microservices, each has its own location. Remember also, that the location can be changed dynamically. So, our app will have to figure out to which services particular

requests should be sent. Moreover, the dynamically changing location makes it almost impossible to have a reliable way for our client mobile app to determine the address and port of each service.

The solution is similar to our previous example with IPC on the desktop. We may deploy one service at a fixed known location, that will accept all the requests from clients and forward each request to the appropriate microservice. Such a pattern is called API Gateway.

Below is the diagram demonstrating how our example microservices may look like using Gateway:

Additionally, this approach allows unifying communication protocol. That is, different services may use different protocols. E.g., some may use REST, some AMQP, and so on. With API Gateway these details are hidden from the client: the client just queries the Gateway using a single protocol (usually, but not necessarily REST) and then the Gateway translates those requests into the appropriate protocol a particular microservice uses.

Configuring microservices

When developing a desktop or mobile app we have several devices the app should run on during its lifecycle. First, it runs on the local device (either computer or mobile device/simulator in case of mobile app) of the developers who work on the app. Then it’s usually run on some dev device to perform unit tests as part of CI/CD. After that, it’s installed on a test device/machine for either manual or automated testing. Finally, after the app is released it is installed on users’ machines/devices. Each type of device

(local, dev, test, user) implies its own environment. For instance, a local app usually uses dev backend API that is connected to dev database. In the case of mobile apps, you may even develop using a simulator, that has its own specifics, like lack or limitation of certain system API. The backend for the app’s test environment has DB with a configuration that is very close to the one used for the release app. So, each environment requires a separate configuration for the app, e.g., server address, simulator specific settings, etc. With a microservices-based web app, we have a similar situation. Our microservices usually run in different environments. Typically they are dev, test, staging, and production. Hardcoding configuration is no option for our microservices, as we typically move the same app package from one environment to another without rebuilding it. So, it’s natural to have the configuration external to the app. At a minimum, we may specify a configuration set per each environment inside the app. While such an approach is good for desktop/mobile apps it has provides a limitation for a web app. We typically move the same app package/file from one environment to another without recompiling it. A better approach is to externalize our configuration. We may store configuration data in database or external files that are available to our microservices. Each microservice reads its configuration on startup. The additional benefit of such an approach is that when the configuration is updated the app may read it on the fly, without the need for rebuilding and/or redeploying it.

Choosing cloud environment

We have our app developed with a microservices approach. The important thing to consider is where would we run our microservices. We should choose the environment that allows us to take advantage of microservice architecture. For cloud solutions, there are two basic types of environment: Infrastructure as a Service, or IaaS, and Platform as a Service, or PaaS. Both have ready-to-use solutions and features that allow scalability, maintainability, reliability which require much effort to achieve on on-premises. and Each of them has advantages compared to traditional on-premises servers.

Summary

In this article, we’ve described key features of microservices architecture for the cloud-native environment. The advantages of microservices are:

- app scalability;

- reliability;

- faster and easier development

- better testability.

To fully take advantage of microservice architecture we should use IaaS or PasS cloud environment type.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.