5 concourse CI tips: How to speed up your builds and pipeline development

With ever-growing IT projects, automation is nowadays a must-have. From building source code and testing to versioning and deploying, CI/CD tools were always the anonymous team member, who did the job no developer was eager to do. Today, we will take a look at some tips regarding one of the newest tools - Concourse CI. First, we will speed up our Concourse jobs, then we’ll ease the development of the new pipelines for our projects.

Aggregate your steps

By default, Concourse tasks in a job are executed separately. This is perfectly fine for small Concourse jobs that last a minute or two. It also works well at the beginning of the project, as we just want to get the process running. But at some point, it would be nice to optimize our builds.

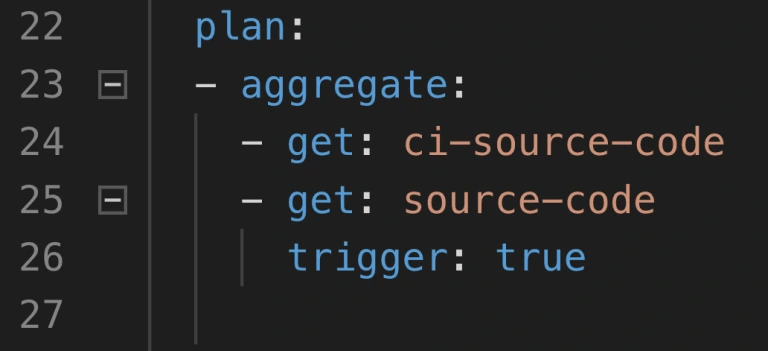

The simplest way to save time is to start using the aggregate keyword. It runs all the steps declared inside of it in parallel. This leads to time-savings in both - script logic execution and in the overhead that occurs when starting the next task.

Neat, so where can we use it? There are 2 main parts of a job where the aggregation is useful:

1. Resource download and upload.

2. Tests execution.

Get and put statements are ideal targets because download and upload of resources are usually completely independent. Integration tests, contract tests, dependency vulnerabilities tests, and alike are also likely candidates if they don’t interfere with one another. Project build tasks? Probably not, because those are usually sequential and we require their output to proceed.

How much time can aggregating save? Of course, it depends. Assuming we can’t aggregate steps that build and test our code, we do get the advantage of simultaneous upload and download of our resources as well as we get less visible step-to-step overhead. We usually save up to two, maybe even three minutes. The largest saving we got was from over half an hour to below ten minutes. Most of the saved time came from running test-related tasks in parallel.

Use docker images with built-in tools

This improvement is trickier to implement but yields a noticeable build time gains. Each task runs in a container, and the image for that container has a certain set of tools available. At some point in the project comes a time where no available image has the tool required. First thing developers do is they download that tool manually or install it using a package manager as a part of the task execution. This means that the tool is fetched every time the task runs. On top of that, the console output is flooded with tool installation logs.

The solution is to prepare a custom container image that already has everything needed for a task to complete. This requires some knowledge not directly related to Concourse, but for example to Docker. With a short dockerfile and a couple of terminal commands, we get an image with the tools we need.

1. Create dockerfile.

2. Inside of the file, install or copy your tools using RUN or COPY commands.

3. Build the image using docker build.

4. Tag and push the image to the registry.

5. Change image_resource part in your Concourse task to use the new image.

That’s it, no more waiting for tools to install each time! We could even create a pipeline to build and push the image for us.

Create pipelines from a template

Moving from time-saving measures to developer convenience tips, here’s one for bigger projects. Those usually have a certain set of similar build pipelines with the only differences being credentials, service names, etc. - parameters that are not hardcoded in the pipeline script and are injected at execution time from a source like CredHub. This is typical for Cloud Foundry and Kubernetes web projects with microservices. With a little bit of creativity, we could get a bash or python script to generate those pipelines from a single template file.

First, we need to have a template file. Take one of your existing pipeline specifications and substitute parameter names with their pipeline agnostic version. Our script needs to loop over a pipeline names list, substitute generic parameter names with proper pipeline related ones that are available in Credhub and then set the pipeline in Concourse with the fly CLI.

The second part of the equation here is a Concourse job that watches for changes in the template file in a Git repository and starts the pipeline generation script. With this solution, we have to change only one file to get all pipelines updated, and on top of that, a commit to pipeline repository is sufficient to trigger the update.

Log into a task container to debug issues

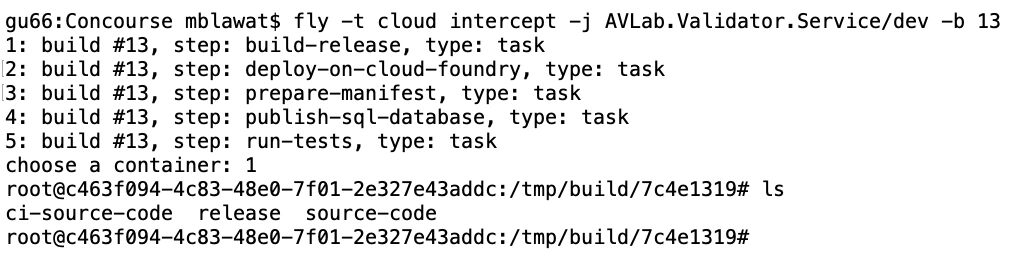

When debugging Concourse task failures, the main source of information on failure is the console. A quick glance at the output is enough to solve most of the problems. Other issues may require a quick peek into the environment of an unsuccessful task. We can do that with fly intercept command.

Fly intercept allows us to log into a container that executed a specific task in a specific job run. Inside we can see the state of the container when task finished and can try to find the root of failure. There may be an empty environment variable - we forgot to set the proper param in a yml file. The resource has a different structure inside of it - we need to change the task script or the resource structure. When the work is done, don’t forget to log out of the container. Oh, and don’t wait too long! Those containers can be disposed of by Concourse at any time.

Use Visual Studio Code Concourse add-on

The last thing I want to talk about is the Concourse CI Pipeline Editor for Visual Studio Code. It’s a plugin that offers suggestions, documentation popups, and error checking for Concourse yml files. If you use the pipeline template and generation task from the previous tip, then any syntax error in your template will be discovered as late as the update task updating the pipelines from the template. That’s because you won’t run fly set-pipeline yourself. Fixing such issue requires a new commit in the pipeline repository.

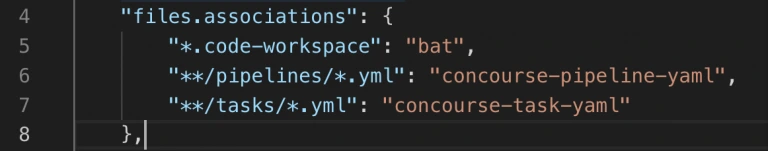

With the plugin, any unused resource or a typo in property name will be detected immediately. Add-on will also help you write new pieces of automation code by suggesting keywords and showing available values for Concourse commands. The only action required is to update the files.associations section in the settings. We use separate directories for pipelines and tasks, so we have set it up as follows:

Conclusion

And that’s it! We hope you have found at least one tip useful and will use it in your project. Aggregate is an easy one to implement, and it’s good to have a habit of aggregating steps from the start. Custom images and pipeline templates are beneficial in bigger projects where they help keep CI less clunky. Finally, fly intercept and the VSC add-on are just extra tools to save time during the pipeline development.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.