Train your computer with the Julia programming language - introduction

As the Julia programming language is becoming very popular in building machine learning applications, we explain its advantages and suggest how to leverage them.

Python and its ecosystem have dominated the machine learning world – that’s an undeniable fact. And it happened for a reason. Ease of use and simple syntax undoubtedly contributed to still growing popularity. The code is understandable by humans, and developers can focus on solving an ML problem instead of focusing on the technical nuances of the language. But certainly, the most significant source of technology success comes from community effort and the availability of useful libraries.

In that context, the Python environment really shines. We can google in five seconds a possible solution for a great majority of issues related to the language, libraries, and useful examples, including theoretical and practical aspects of our intelligent application or scientific work. Most of the machine learning related tutorials and online courses are embedded in the Python ecosystem. If some ML or AI algorithm is worth of community’s attention, there is a huge probability that somebody implemented it as a Python open-source library.

Python is also the "Programming Language of the 2020" award winner. The award is given to the programming language that has the highest rise in ratings in a year based on the TIOBE programming community index (a measure of the popularity of programming languages). It is worth noting that the rise of Python language popularity is strongly correlated with the rise of machine learning popularity.

Equipped with such great technology, why still are we eager to waste a lot of our time looking for something better? Except for such reasons as being bored or the fact that many people don’t like snakes (although the name comes from „Monty Python’s Flying Circus”, a python still remains a snake). We think that the answer is quite simple: because we can do it better.

From Python to Julia

To understand that there is a potential to improve, we can go back to the early nineties when Python was created. It was before 3rd wave of artificial intelligence popularity and before the exponential increase in interest in deep learning. Some hard-to-change design decisions that don’t fit modern machine learning approaches were unavoidable. Python is old, it’s a fact, a great advantage, but also a disadvantage. A lot of great and groundbreaking things happened from the times when Python was born.

While Python has dominated the ML world, a great alternative has emerged for anyone who expects more. The Julia Language was created in 2009 by a four-person team from MIT and released in 2012. The authors wanted to address the shortcomings in Python and other languages. Also, as they were scientists, they focused on scientific and numerical computation, hitting a niche occupied by MATLAB, which is very good for that application but is not free and not open source. The Julia programming language combines the speed of C with the ease of use of Python to satisfy both scientists and software developers. And it integrates with all of them seamlessly.

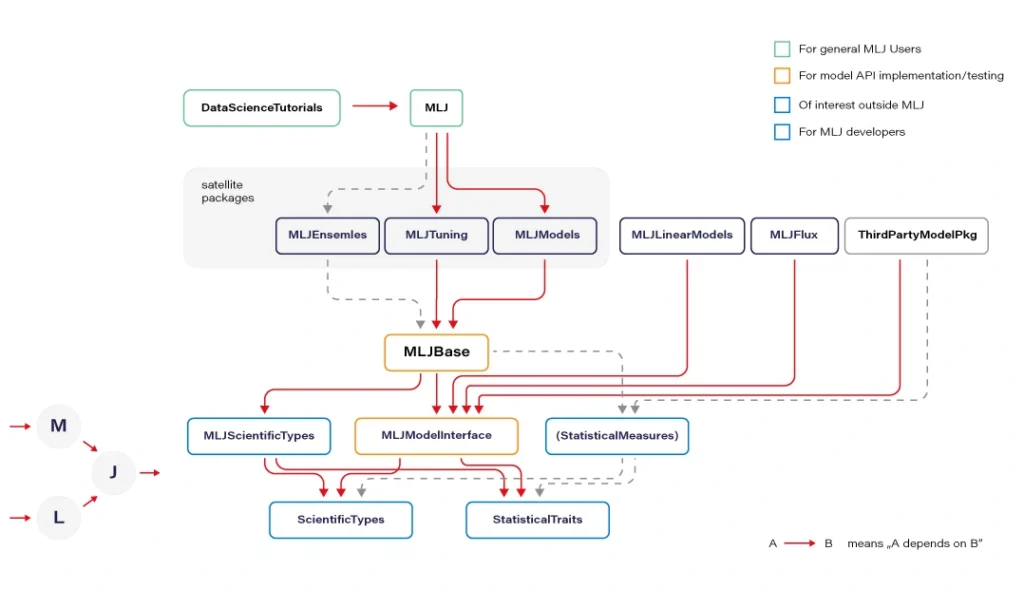

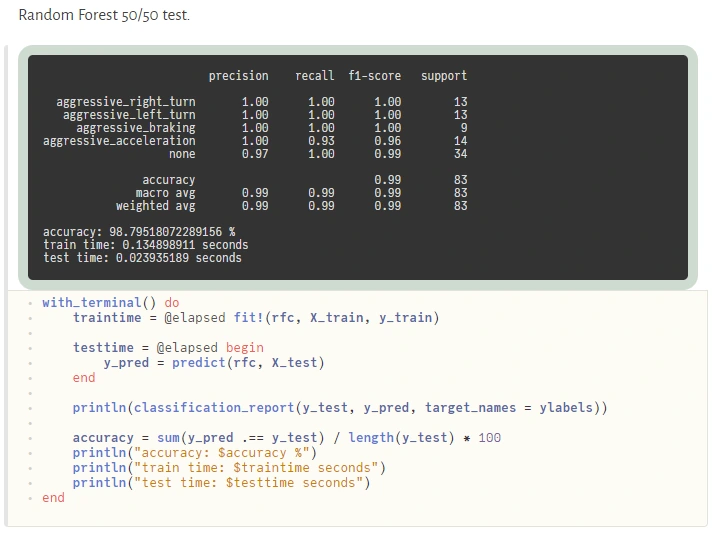

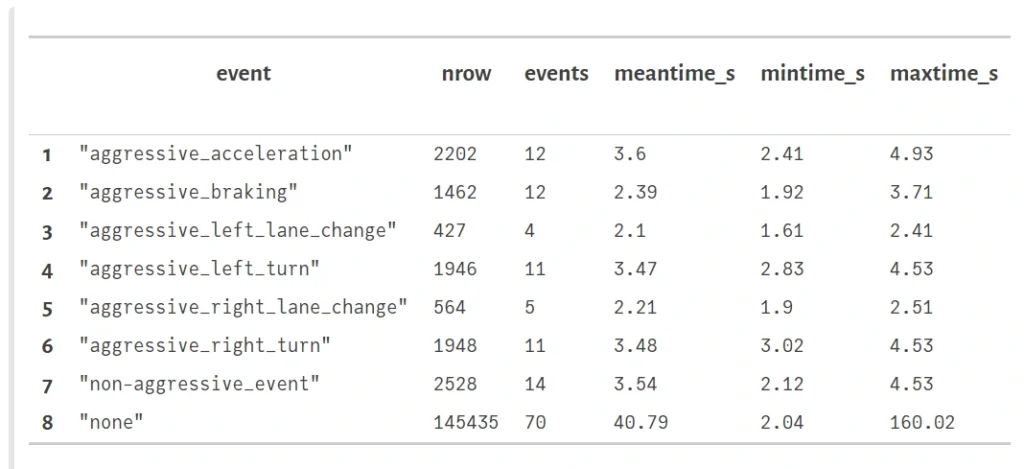

In the following sections, we will show you how the Julia Language can be adapted to every Machine Learning problem . We will cover the core features of the language shown in the context of their usefulness in machine learning and comparison with other languages. A short overview of machine learning tools and frameworks available in Julia is also included. Tools for data preparation, visualization of results, and creating production pipelines also are covered. You will see how easily you can use ML libraries written in other languages like Python, MATLAB, or C/C++ using powerful metaprogramming features of the Julia language. The last part presents how to use Julia in practice, both for rapid prototyping and building cloud-based production pipelines.

The Julia language

Someone said if Python is a premium BMW sedan (petrol only, I guess, eventual hybrid) then Julia is a flagship Tesla. BMW has everything you need, but more and more people are buying Tesla. I can somehow agree with that, and let me explain the core features of the language which makes Julia so special and let her compete for a place in the TIOBE ranking with such great players as LISP, Scala, or Kotlin (31st place in March 2021).

Unusual JIT/AOT complier

Julia uses the LLVM compiler framework behind the scenes to translate very simple and dynamic syntax into machine code. This happens in two main steps. The first step is precompilation, before final code execution, and what may be surprising this it actually runs the code and stores some precompilation effects in the cache. It makes runtime faster but slower building – usually this is an acceptable cost.

The second step occurs in runtime. The compiler generates code just before execution based on runtime types and static code analysis. This is not how traditional just-in-time compilers work e.g., in Java. In “pure” JIT the compiler is not invoked until after a significant number of executions of the code to be compiled. In that context, we can say that Julia works in much the same way as C or C++. That’s why some people call Julia compiler a just-ahead-of-time compiler, and that’s why Julia can run near as fast as C in many cases while remaining a dynamic language like Python. And this is just awesome.

Read-eval-print loop

Read-eval-print loop (REPL) is an interactive command line that can be found in many modern programming languages. But in the case of Julia, the REPL can be used as the real heart of the entire development process. It lets you manage virtual environments, offers a special syntax for the package manager, documentation, and system shell interactions, allows you to test any part of your code, the language, libraries, and many more.

Friendly syntax

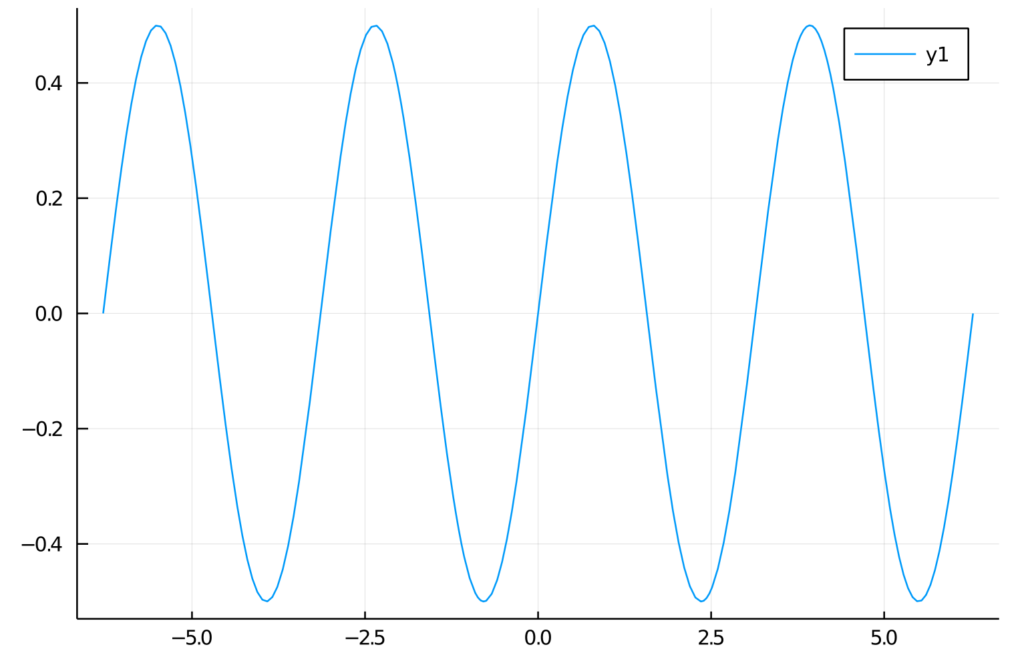

The syntax is similar to MATLAB and Python but also takes the best of other languages like LISP. Scientists will appreciate that Unicode characters can be used directly in source code, for example, this equation: f(X,u,σᵀ∇u,p,t) = -λ * sum(σᵀ∇u.^2)

is a perfectly valid Julia code. You may notice how cool it can be in terms of machine learning. We use these symbols in machine learning related books and articles, why not use them in source code?

Optional typing

We can think of Julia as dynamically typed but using type annotation syntax, we can treat variables as being statically typed, and improve performance in cases where the compiler could not automatically infer the type. This approach is called optional typing and can be found in many programming languages. In Julia however, if used properly, can result in a great boost of performance as this approach fits very well with the way Julia compiler works.

A ‘Glue’ language

Julia can interface directly with external libraries written in C, C++, and Fortran without glue code. Interface with Python code using PyCall library works so well that you can seamlessly use almost all the benefits of great machine learning Python ecosystem in Julia project as if it were native code! For example, you can write:

np = pyimport(numpy)

and use numpy in the same way you do with Python using Julia syntax. And you can configure a separate miniconda Python interpreter for each project and set up everything with one command as with Docker or similar tools. There are bindings to other languages as well e.g., Java, MATLAB, or R.

Julia supports metaprogramming

One of Julia's biggest advantages is Lisp-inspired metaprogramming. A very powerful characteristic called homoiconicity explained by a famous sentence: “code is data and data is code” allows Julia programs to generate other Julia programs, and even modify their own code. This approach to metaprogramming gives us so much flexibility, and that’s how developers do magic in Julia.

Functional style

Julia is not an object-oriented language. Something like a model.fit() function call is possible (Julia is very flexible) but not common in Julia. Instead, we write fit(model) , and it's not about the syntax, but it is about the organization of all code in our program (modules, multiple dispatches, functions as a first-class citizen, and many more).

Parallelization and distributed computing

Designed with ML in mind, Julia focusses on the scientific computing domain and its needs like parallel, distributed intensive computation tasks. And the syntax is very easy for local or remote parallelism.

Disadvantages

Well, it might be good if the compiler wasn't that slow, but it keeps getting better. Sometimes REPL could be faster, but again it’s getting better, and it depends on the host operating system.

Conclusion

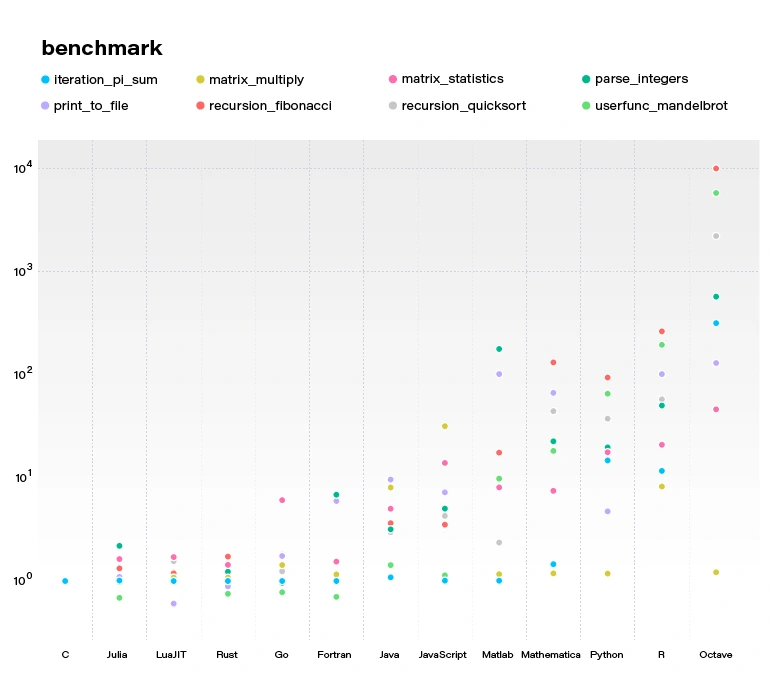

By concluding this section, we would like to demonstrate a benchmark comparing several popular languages and Julia. All language benchmarks should be treated not too seriously, but they still give an approximate view of the situation.

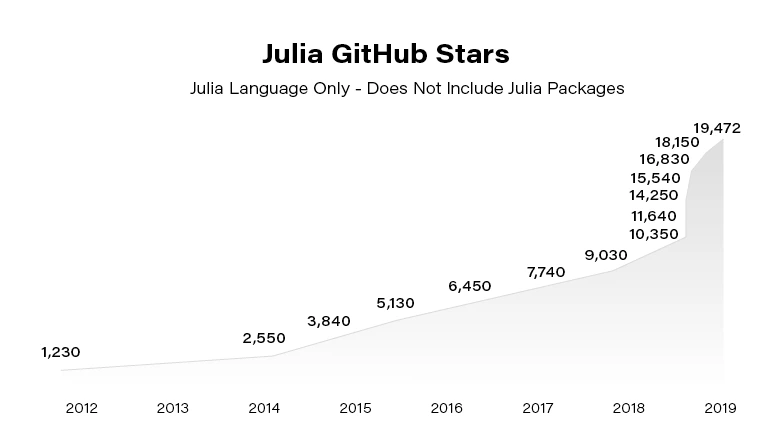

Julia becomes more and more popular. Since the 2012 launch, Julia has been downloaded over 25,000,000 times as of February 2021, up by 87% in a year.

In the next article, we focus on using Julia in building Machine Learning models. You can also check our guide to getting started with the language .

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.