Monitoring your microservices on AWS with Terraform and Grafana - basic microservices architecture

Do you have an application in the AWS cloud? Do you have several microservices you would like to monitor? Or maybe you’re starting your new project and looking for some good-looking, well-designed infrastructure? Look no further - you are in the right place!

We’ve spent some time building and managing microservices and cloud-native infrastructure so we provide you with a guide covering the main challenges and proven solutions.

In this series, we describe the following topics:

- How to create a well-designed architecture with microservices and a cloud-config server?

- How to collect metrics and logs in a common dashboard?

- How to secure the entire stack?

Monitoring your microservices - assumptions

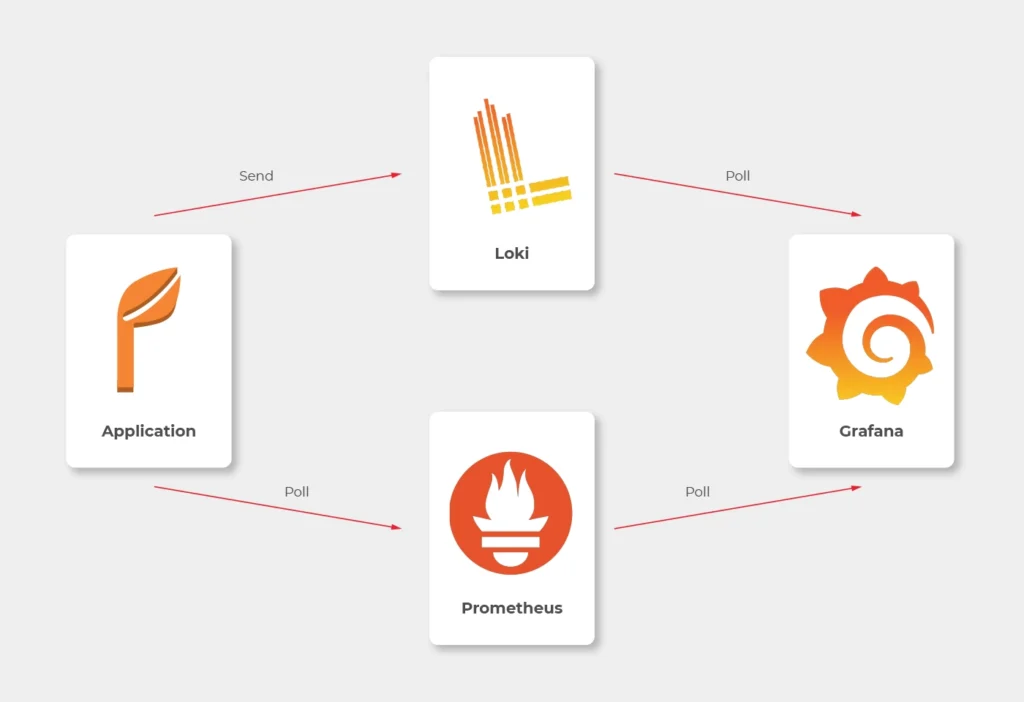

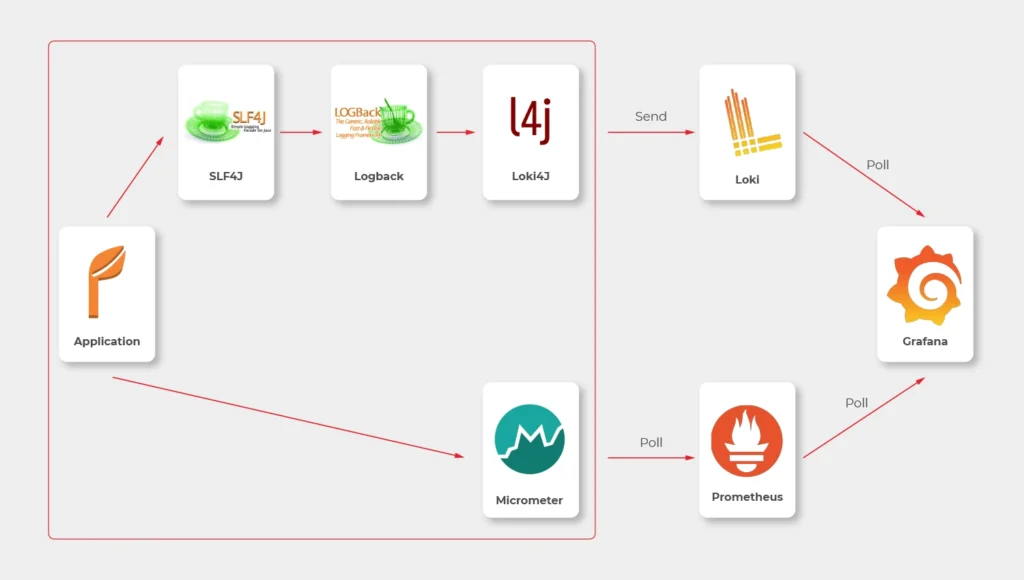

Choosing Grafana for such a project seems obvious, as the tool is powerful, fast, user-friendly, customizable, and easy to maintain. Grafana works perfectly with Prometheus and Loki. Prometheus is a metric sink that collects metrics from multiple sources and sends them to the target monitoring system. Loki does the very same operation for logs. Both collectors are designed to be integrated with Grafana.

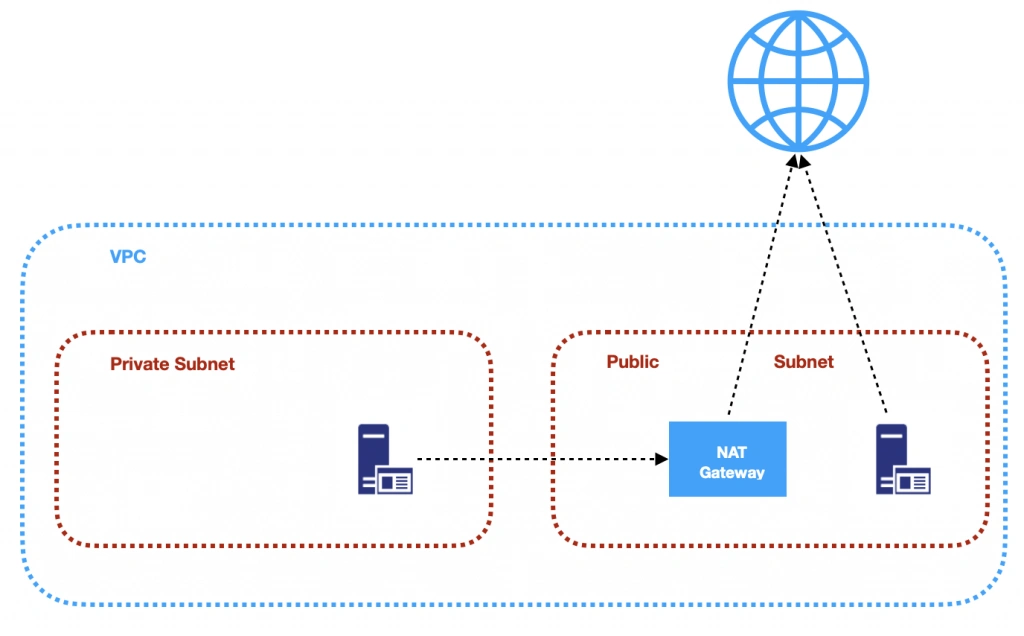

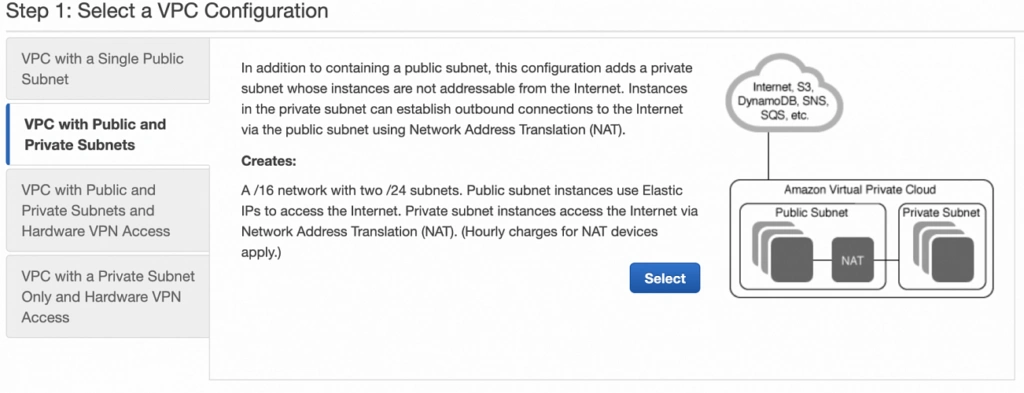

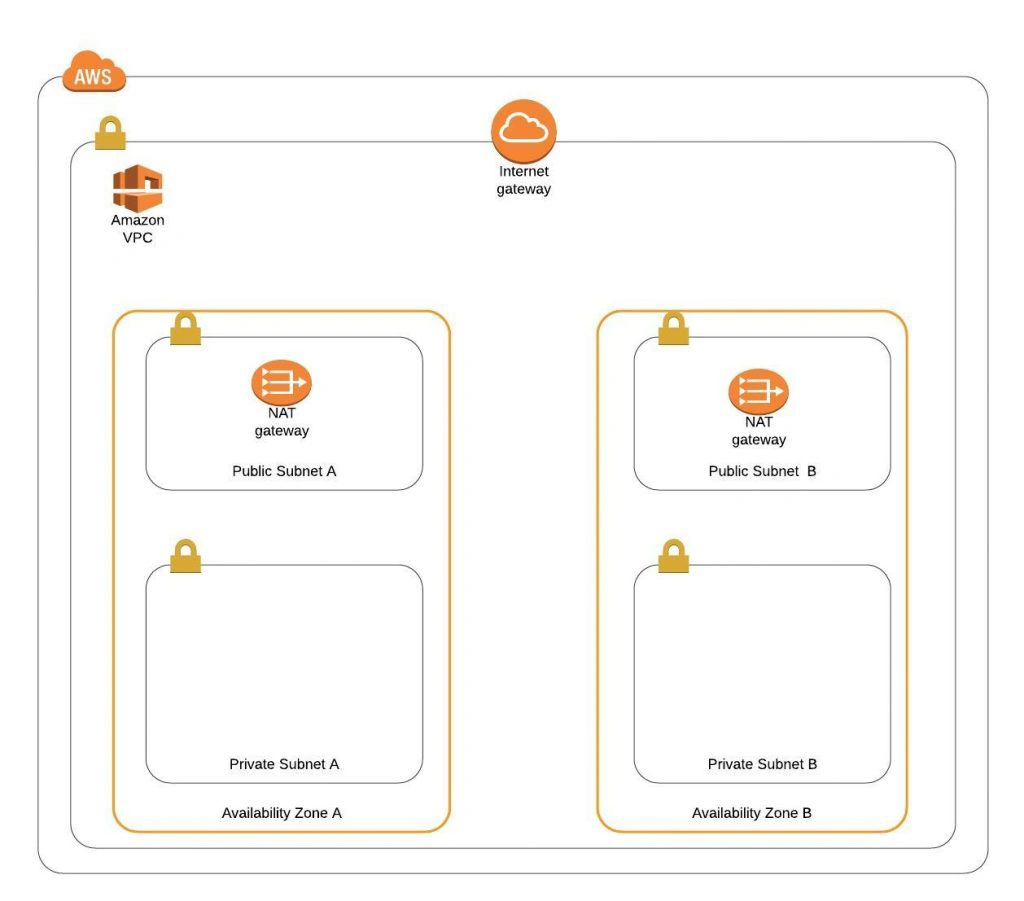

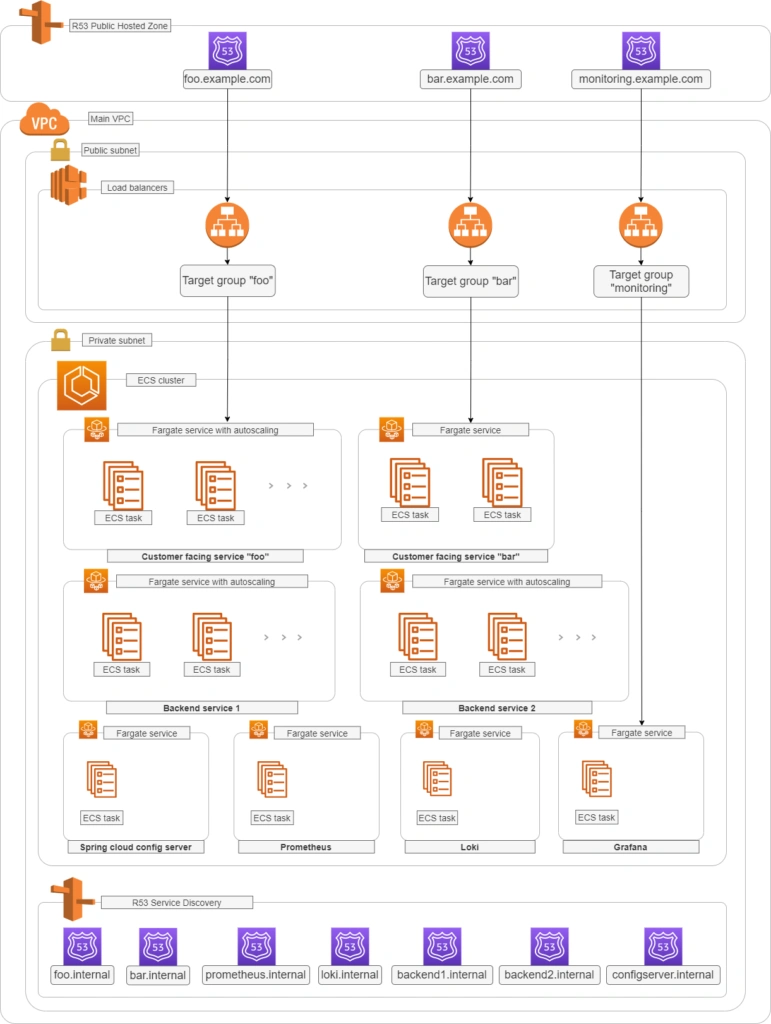

See the diagram below to better understand our architecture:

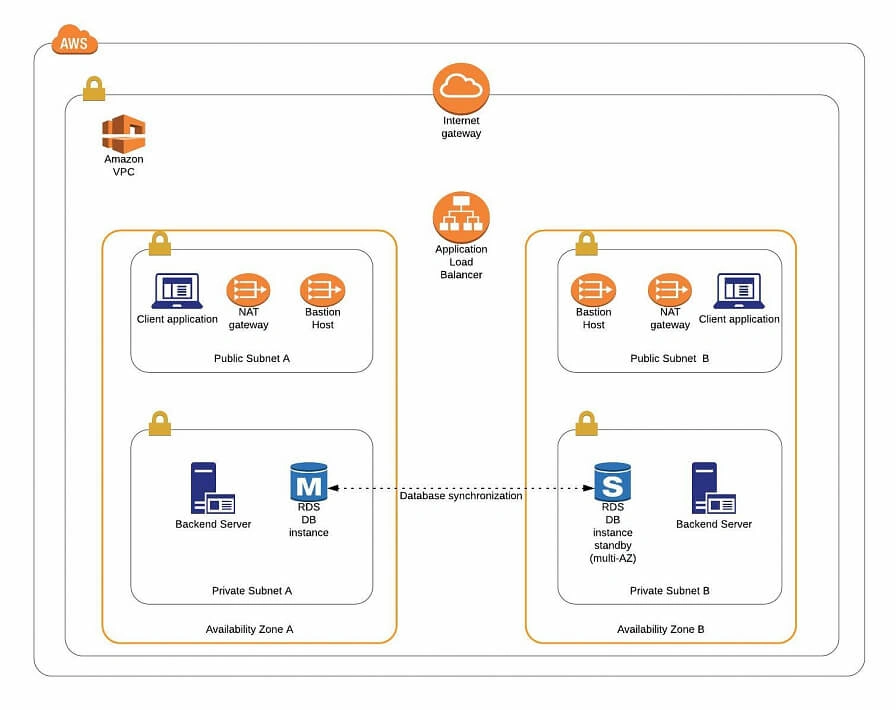

Let’s analyze the diagram for a moment. On the top, there is a publicly visible hosted zone in Route 53, the DNS “entry” to our system, with 3 records: two application services available over the internet and an additional monitoring service for our internal purposes.

Below, there is a main VPC with two subnets: public and private. In the public one, we have load balancers only, and in the private one, there is an ECS cluster. In the cluster, we have few services running using Fargate: two with internet-available APIs, two for internal purposes, one Spring Cloud Config Server, and our monitoring stack: Loki, Prometheus, and Grafana. At the bottom of the diagram, you can also find a Service Discovery service (AWS CloudMap) that creates entries in Route 53, to enable communication inside our private subnet.

Of course, for readability reasons, we omit VPC configuration, services dependencies (RDS, Dynamo, etc.), CI/CD, and all other services around the core. You can follow this guide covering building AWS infrastructure.

To sum up our assumptions:

- We use an infra-as-a-code approach with Terraform

- There are few Internet-facing services and few for internal purposes in our private subnet

- Internet-facing services are exposed via load balancers in the public subnet

- We use the Fargate launch type for ECS tasks

- Some services can be scaled with ECS auto-scaling groups

- We use Service Discovery to redeploy and scale without manual change of IP’s, URL’s or target groups

- We don’t want to repeat ourselves so we use a Spring Cloud Config Server as a main source of configuration

- We use Grafana to see synchronized metrics and logs

- (what you cannot see on the diagram) We use encrypted communication everywhere - including communication between services in a private subnet

Basic AWS resources

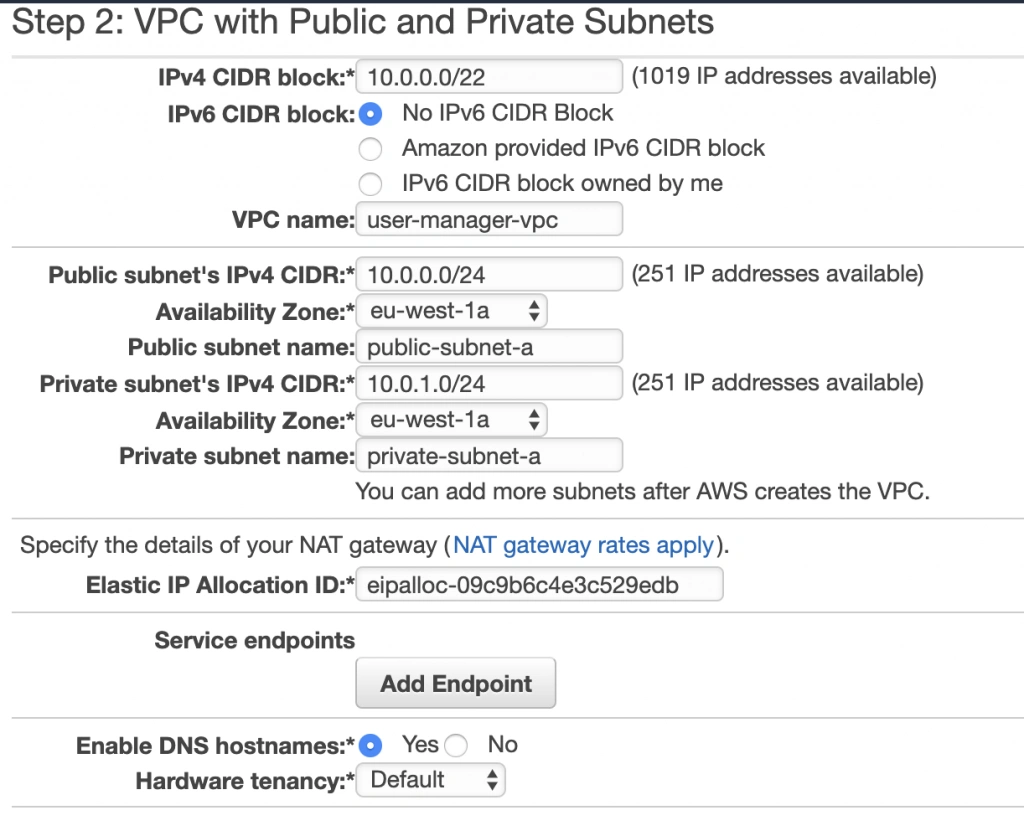

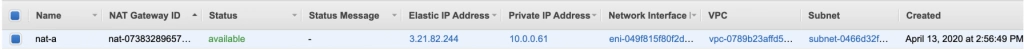

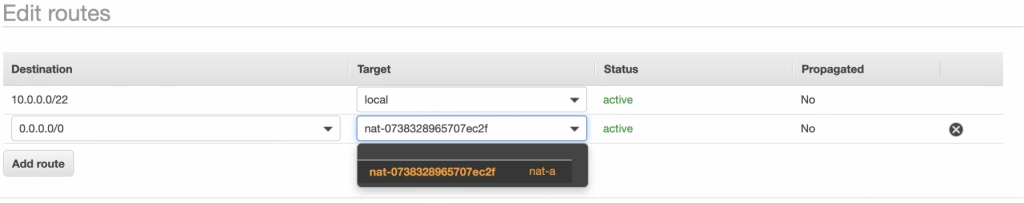

In this article, we assume you have all basic resources already created and correctly configured: VPC, subnets, general security groups, network ACLs, network interfaces, etc. Therefore we’re going to focus on resources visible on the diagram above, crucial from a monitoring point of view.

Let’s create the first common resource:

resource "aws_service_discovery_private_dns_namespace" "namespace_for_environment" {

name = "internal"

vpc = var.vpc_id

}

This is the Service Discovery visible in the lower part of the diagram. We’re going to fill it in a moment.

By the way, above, you can see an example, how we’re going to present listings. You will need to adjust some variables for your needs (like var .vpc_id ). We strongly recommend using Terragrunt to manage dependencies between your Terraform modules, but it’s out of the scope of this paper.

Your services without monitoring

Internet-facing services

Now let’s start with the first application. We need something to monitor.

resource "aws_route53_record" "foo_entrypoint" {

zone_id = var.zone_environment_id

name = "foo"

type = "A"

set_identifier = "foo.example.com"

alias {

name = aws_lb.foo_ecs_alb.dns_name

zone_id = aws_lb.foo_ecs_alb.zone_id

evaluate_target_health = true

}

latency_routing_policy {

region = var.default_region

}

}

This is an entry for Route53 to access the internet-facing “foo” service. We’ll use it to validate a TLS certificate later.

resource "aws_lb" "foo_ecs_alb" {

name = "foo"

internal = false

load_balancer_type = "application"

security_groups = [

aws_security_group.alb_sg.id

]

subnets = var.vpc_public_subnet_ids

}

resource "aws_lb_target_group" "foo_target_group" {

name = "foo"

port = 8080

protocol = "HTTP"

target_type = "ip"

vpc_id = var.vpc_id

health_check {

port = 8080

protocol = "HTTP"

path = "/actuator/health"

matcher = "200"

}

depends_on = [

aws_lb.foo_ecs_alb

]

}

resource "aws_lb_listener" "foo_http_listener" {

load_balancer_arn = aws_lb.foo_ecs_alb.arn

port = "8080"

protocol = "HTTP"

default_action {

type = "forward"

target_group_arn = aws_lb_target_group.foo_target_group.arn

}

}

resource "aws_security_group" "alb_sg" {

name = "alb-sg"

description = "Inet to ALB"

vpc_id = var.vpc_id

ingress {

protocol = "tcp"

from_port = 8080

to_port = 8080

cidr_blocks = [

"0.0.0.0/0"

]

}

egress {

protocol = "-1"

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

cidr_blocks = [

"0.0.0.0/0"

]

}

}

OK, what do we have so far?

Besides the R53 entry, we’ve just created a load balancer, accepting traffic on 8080 port and transferring it to the target group called foo_target_group . We use a default Spring Boot " /actuator/health " health check endpoint (you need to have spring-boot-starter-actuator dependency in your pom) and a security group allowing ingress traffic to reach the load balancer and all egress traffic from the load balancer.

Now, let’s create the service.

resource "aws_ecr_repository" "foo_repository" {

name = "foo"

}

resource "aws_ecs_task_definition" "foo_ecs_task_definition" {

family = "foo"

network_mode = "awsvpc"

requires_compatibilities = ["FARGATE"]

cpu = "512"

memory = "1024"

execution_role_arn = var.ecs_execution_role_arn

container_definitions = <<TASK_DEFINITION

[

{

"cpu": 512,

"image": "${aws_ecr_repository.foo_repository.repository_url}:latest",

"memory": 1024,

"memoryReservation" : 512,

"name": "foo",

"networkMode": "awsvpc",

"essential": true,

"environment" : [

{ "name" : "SPRING_CLOUD_CONFIG_SERVER_URL", "value" : "configserver.internal" },

{ "name" : "APPLICATION_NAME", "value" : "foo" }

],

"portMappings": [

{

"containerPort": 8080,

"hostPort": 8080

}

]

}

]

TASK_DEFINITION

}

resource "aws_ecs_service" "foo_service" {

name = "foo"

cluster = var.ecs_cluster_id

task_definition = aws_ecs_task_definition.foo_ecs_task_definition.arn

desired_count = 2

launch_type = "FARGATE"

network_configuration {

subnets = var.vpc_private_subnet_ids

security_groups = [

aws_security_group.foo_lb_to_ecs.id,

aws_security_group.ecs_ecr_security_group.id,

aws_security_group.private_security_group.id

]

}

service_registries {

registry_arn = aws_service_discovery_service.foo_discovery_service.arn

}

load_balancer {

target_group_arn = aws_lb_target_group.foo_target_group.arn

container_name = "foo"

container_port = 8080

}

depends_on = [aws_lb.foo_ecs_alb]

}

You can find just three resources above, but a lot of configuration. The first one is easy - just an ECR for the image of your application. Then we have a task definition. Please pay attention to environment variables SPRING_CLOUD_CONFIG_SERVER_URL - this is an address of our config server inside our internal Service Discovery domain. The third one is an ECS service.

As you can see, it uses some magic of ECS Fargate - automatically registering new tasks in a Service Discovery ( service_registries section) and a load balancer ( load_balancer section). We just need to wait until the load balancer is created ( depends_on = [aws_lb.foo_ecs_alb] ). If you want to add some autoscaling, this is the right place to put it in. You’re also ready to push your application to the ECR if you already have one. We’re going to cover the application's important content later in this article. The ecs_execution_role_arn is just a standard role with AmazonECSTaskExecutionRolePolicy , allowed to be assumed by ECS and ecs-tasks.

Let’s discuss security groups now.

resource "aws_security_group" "foo_lb_to_ecs" {

name = "allow_lb_inbound_foo"

description = "Allow inbound Load Balancer calls"

vpc_id = var.vpc_id

ingress {

from_port = 8080

protocol = "tcp"

to_port = 8080

security_groups = [aws_security_group.foo_alb_sg.id]

}

}

resource "aws_security_group" "ecs_to_ecr" {

name = "allow_ecr_outbound"

description = "Allow outbound traffic for ECS task, to ECR/docker hub"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

egress {

from_port = 443

to_port = 443

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

egress {

from_port = 53

to_port = 53

protocol = "udp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

egress {

from_port = 53

to_port = 53

protocol = "tcp"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}

resource "aws_security_group" "private_inbound" {

name = "allow_inbound_within_sg"

description = "Allow inbound traffic inside this SG"

vpc_id = var.vpc_id

ingress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

self = true

}

egress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

self = true

}

}

As you can see, we use three groups - all needed. The first one allows the load balancer located in the public subnet to call the task inside the private subnet. The second one allows our ECS task to poll its image from the ECR. The last one allows our services inside the private subnet to talk to each other - such communication is allowed by default, only if you don’t attach any specific group (like the load balancer’s one), therefore we need to explicitly permit this communication.

There is just one piece needed to finish the “foo” service infrastructure - the service discovery service entry.

resource "aws_service_discovery_service" "foo_discovery_service" {

name = "foo"

description = "Discovery service name for foo"

dns_config {

namespace_id = aws_service_discovery_private_dns_namespace.namespace_for_environment.id

dns_records {

ttl = 100

type = "A"

}

}

}

It creates a “foo” record in an “internal” zone. So little and yet so much. The important thing here is - this is a multivalue record, which means it can cover 1+ entries - it provides basic, equal-weight autoscaling during normal operation but Prometheus can dig out from such a record each IP address separately to monitor all instances.

Now some good news - you can simply copy-paste the code of all resources with names prefixed with “foo_” and create “bar_” clones for the second, internet-facing service in the project. This is what we love Terraform for.

Backend services (private subnet)

This part is almost the same as the previous one, but we can simplify some elements.

resource "aws_ecr_repository" "backend_1_repository" {

name = "backend_1"

}

resource "aws_ecs_task_definition" "backend_1_ecs_task_definition" {

family = "backend_1"

network_mode = "awsvpc"

requires_compatibilities = ["FARGATE"]

cpu = "512"

memory = "1024"

execution_role_arn = var.ecs_execution_role_arn

container_definitions = <<TASK_DEFINITION

[

{

"cpu": 512,

"image": "${aws_ecr_repository.backend_1_repository.repository_url}:latest",

"memory": 1024,

"memoryReservation" : 512,

"name": "backend_1",

"networkMode": "awsvpc",

"essential": true,

"environment" : [

{ "name" : "_JAVA_OPTIONS", "value" : "-Xmx1024m -Xms512m" },

{ "name" : "SPRING_CLOUD_CONFIG_SERVER_URL", "value" : "configserver.internal" },

{ "name" : "APPLICATION_NAME", "value" : "backend_1" }

],

"portMappings": [

{

"containerPort": 8080,

"hostPort": 8080

}

]

}

]

TASK_DEFINITION

}

resource "aws_ecs_service" "backend_1_service" {

name = "backend_1"

cluster = var.ecs_cluster_id

task_definition = aws_ecs_task_definition.backend_1_ecs_task_definition.arn

desired_count = 1

launch_type = "FARGATE"

network_configuration {

subnets = var.vpc_private_subnet_ids

security_groups = [

aws_security_group.ecs_ecr_security_group.id,

aws_security_group.private_security_group.id

]

}

service_registries {

registry_arn = aws_service_discovery_service.backend_1_discovery_service.arn

}

}

resource "aws_service_discovery_service" "backend_1_discovery_service" {

name = "backend1"

description = "Discovery service name for backend 1"

dns_config {

namespace_id = aws_service_discovery_private_dns_namespace.namespace_for_environment.id

dns_records {

ttl = 100

type = "A"

}

}

}

As you can see, all resources related to the load balancer are gone. Now, you can copy the code about creating the backend_2 service.

So far, so good. We have created 4 services, but none will start without the config server yet.

Config server

The infrastructure for the config server is similar to the backed services described above. It simply needs to know all other services’ URLs. In the real-world scenario, the configuration may be stored in a git repository or in the DB, but it’s not needed for this article, so we’ve used a native config provider, with all config files stored locally.

We would like to dive into some code here, but there is not much in this module yet. To make it just working, we only need this piece of code:

@SpringBootApplication

@EnableConfigServer

public class CloudConfigServer {

public static void main(String[] arguments) {

run(CloudConfigServer.class, arguments);

}

}

and few dependencies.

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-config-server</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-security</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-web</artifactId>

</dependency>

We also need some extra config in the pom.xml file.

<parent>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-starter-parent</artifactId>

<version>2.4.2</version>

</parent>

<dependencyManagement>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-dependencies</artifactId>

<version>2020.0.1</version>

<type>pom</type>

<scope>import</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

</dependencyManagement>

<build>

<plugins>

<plugin>

<groupId>org.springframework.boot</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-boot-maven-plugin</artifactId>

</plugin>

</plugins>

</build>

That’s basically it - you have your own config server. Now, let’s put some config inside. The Structure of the server is as follows.

config_server/

├─ src/

│ ├─ main/

│ ├─ java/

│ ├─ com/

│ ├─ example/

│ ├─ CloudConfigServer.java

│ ├─ resources/

│ ├─ application.yml (1)

│ ├─ configforclients/

│ ├─ application.yml (2)

As there are two files called application.yml we’ve added numbers (1), (2) at the end of lines to distinguish them. So the application.yml (1) file is there to configure the config server itself. Its content is as follows:

server:

port: 8888

spring:

application:

name: spring-cloud-config-server

profiles:

include: native

cloud:

config:

server:

native:

searchLocations: classpath:/configforclients

management:

endpoints:

web:

exposure:

include: health

With the “native” configuration, the entire classpath:/ and classpath:/config are taken as a configuration for remote clients. Therefore, we need this line:

spring.cloud.config.server.native.searchLocations: classpath:/configforclients to distinguish the configuration for the config server itself and for the clients. The client’s configuration is as follows:

address:

foo: ${FOO_URL:http://localhost:8080}

bar: ${BAR_URL:http://localhost:8081}

backend:

one: ${BACKEND_1_URL:http://localhost:8082}

two: ${BACKEND_2_URL:http://localhost:8083}

management:

endpoints:

web:

exposure:

include:health

spring:

jackson:

default-property-inclusion: non_empty

time-zone: Europe/Berlin

As you can see, all service discovery addresses are here, so they can be used by all clients. We also have some common configurations, like Jackson-related, and one important for the infra - to expose health checks for load balancers.

If you use Spring Boot Security (I hope you do), you can disable it here - it will make accessing the config server simpler, and, as it’s located in the private network and we’re going to encrypt all endpoints in a moment - you don’t need it. Here is an additional file to disable it.

@Configuration

@EnableWebSecurity

public class WebSecurityConfig extends WebSecurityConfigurerAdapter {

@Override

public void configure(WebSecurity web) throws Exception {

web.ignoring().antMatchers("/**");

getHttp().csrf().disable();

}

}

Yes, we know, it's strange to use @EnableWebSecurity to disable web security, but it’s how it works. Now, let’s configure clients to read those configurations.

Config clients

First of all, we need two dependencies.

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-starter-bootstrap</artifactId>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.springframework.cloud</groupId>

<artifactId>spring-cloud-starter-config</artifactId>

</dependency>

We assume you have all Spring-Boot related dependencies already in place.

As you can see, we need to use bootstrap, so instead of the application.yml file, we’re going to use bootstrap.yml(which is responsible for loading configuration from external sources):

main:

banner-mode: 'off'

cloud:

config:

uri: ${SPRING_CLOUD_CONFIG_SERVER:http://localhost:8888}

There are only two elements here. We use the first one just to show you that some parameters simply cannot be set using the config server. In this example, main.banner-mode is being read before accessing the config server, so if you want to disable the banner (or change it) - you need to do it in each application separately. The second property - cloud.config.uri - is obviously a pointer to the config server. As you can see, we use a fallback value to be able to run everything both in AWS and local machines.

Now, with this configuration, you can really start every service and make sure that everything works as expected.

Monitoring your microservices - conclusion

That was the easy part. Now you have a working application, exposed and configurable. We hope you can tweak and adjust it for your own needs. In the next part we’ll dive into a monitoring topic.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.