Introduction to Kubernetes security: Container security

Focusing on Kubernetes security, we have to go through container security and their runtimes. All in all, clusters without containers running does not make much sense. Hardening workloads often is much harder than hardening the cluster itself. Let’s start with container configuration.

Basic rules for containers

There are two ways how you can get a container image you want to run. You can build it, or you can use an existing one. If you create your own containers, then you have more control over the process and you have a clear vision of what is inside. But it is now your responsibility to make that image as secure as possible. There are plenty of rules to make your container safer, and here we share the best practices to ensure that.

Minimal image

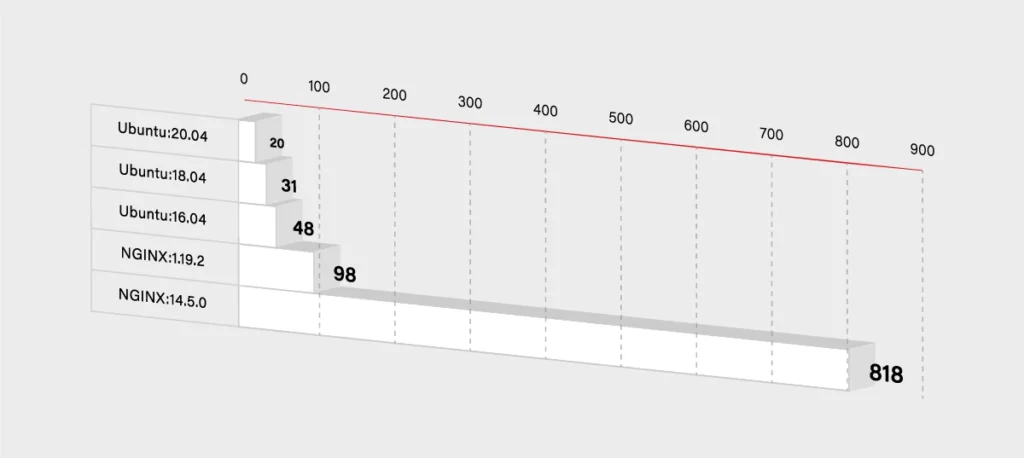

First of all, if you want to start fast, you set some base images with plenty of features built-in. But in the end, it is not a good idea. The larger the base is, the more issues may occur. For example, the nginx image hosted on Docker Hub has 98 known vulnerabilities, and node has more than 800. All of those issues are inherited automatically by your container - unless you mitigate each one in your custom layers. Please take a look at the graph below that shows how the number of those vulnerabilities grows.

So you have to decide if you really need that additional functionality. If not, then you can use some smaller and simpler base images. It will, for sure, lower the number of known vulnerabilities in your container. It should lower the size of the container dramatically as well.

FROM node -> FROM ubuntu

If you really want only your application running in the container, then you can use Docker’s reserved, minimal image scratch:

FROM scratchCOPY hello /CMD [“/hello”]

User vs Root

Another base rule that you should embrace are the privileges inside the container. If you do not specify any, then it uses the root user inside the container. So there is a potential risk that it gets root access on the Docker host. To minimize that threat, you have to use a dedicated user/group in the Docker image. You can use the USER directive for this purpose:

FROM myslq

COPY . /app

RUN chown -R mysql:mysql /app

USER mysql

As you can see in the above example some images have an already defined user, that you can use. In mysql, it is named mysql (what a surprise!). But sometimes you may have to create one on your own:

RUN groupadd -r test && useradd -r -s /bin/false -g test test

WORKDIR /app

COPY . /app

RUN chown -R test:test /app

USER test

Use the specific tag for a base image

Another threat is not so obvious. You may think that the newest version of your base image will be the most secure one. In general, that is true, but it may bring some new risks and issues to your image. If you do not specify a proper version:

FROM ubuntu

Docker will use the latest one. It sounds pretty handy, but in some cases, it may break your build because the version may change between the builds. Just imagine that you are dependent on some package that has been removed in the latest version of the ubuntu image. Another threat is that the latest version may introduce new vulnerabilities that are not yet discovered. To avoid the described issues, it is better to specify the version of your base image:

FROM ubuntu:18.04

If the version is more specific, then there is a lower risk that it will be changed or updated without notice. On the other hand, please note that there is a higher chance that some specific versions will be removed. In that case, it is always a good practice to use the local Docker registry and keep important images mirrored there.

Also, check and keep in mind the versioning schema for the image - focusing on how alfa, beta, and test images are versioned. Being a test rat for the new features is not really what you would like to do.

See what is inside

The rules described above are only a part of a larger set but some of the most important ones. Especially if you create your own container image. But many times, you have to use images from other teams. It may happen when you simply want to run such an image, or you want to use it as a base image.

In both cases, you are at risk that this external image will bring a lot of issues to your application. If you are not a creator of the container image, then you have to pay even more attention to the security. First of all, you should check a Dockerfile to see how the image is built. Below is an example of the Ubuntu:18.04 image Dockerfile:

FROM scratch

ADD ubuntu-bionic-core-cloudimg-amd64-root.tar.gz /

# verify that the APT lists files do not exist

RUN [ -z "$(apt-get indextargets)" ]

# (see https://bugs.launchpad.net/cloud-images/+bug/1699913)

# a few minor docker-specific tweaks

# see https://github.com/docker/docker/blob/9a9fc01af8fb5d98b8eec0740716226fadb373...

RUN set -xe \

\

(...)

# make systemd-detect-virt return "docker"

# See: https://github.com/systemd/systemd/blob/aa0c34279ee40bce2f9681b496922dedbadfca...

RUN mkdir -p /run/systemd && echo 'docker' > /run/systemd/container

CMD ["/bin/bash"]

Unfortunately, a Dockerfile is often not available, and it is not integrated into the image. You have to use Docker inspect command in order to see what is inside:

$ docker inspect ubuntu:18.04

[

{

"Id": "sha256:d27b9ffc56677946e64c1dc85413006d8f27946eeb9505140b094bade0bfb0cc",

"RepoTags": [

"ubuntu:18.04"

],

"RepoDigests": [

"ubuntu@sha256:e5b0b89c846690afe2ce325ac6c6bc3d686219cfa82166fc75c812c1011f0803"

],

"Parent": "",

"Comment": "",

"Created": "2020-07-06T21:56:11.478320417Z",

(...)

"Config": {

"Hostname": "",

"Domainname": "",

"User": "",

"AttachStdin": false,

"AttachStdout": false,

"AttachStderr": false,

"Tty": false,

"OpenStdin": false,

"StdinOnce": false,

"Env": [

"PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin"

],

"Cmd": [

"/bin/bash"

],

"ArgsEscaped": true,

"Image": "sha256:4f2a5734a710e5466a625e279994892c9dd9003d0504d99c8297b01b7138a663",

"Volumes": null,

"WorkingDir": "",

"Entrypoint": null,

"OnBuild": null,

"Labels": null

},

"Architecture": "amd64",

"Os": "linux",

"Size": 64228599,

"VirtualSize": 64228599,

(…)

}

]

It gives you all detailed information about the image in a JSON format, so you can review what is inside. Finally, you can use docker histor y to see the complete history of how the image was created.

$ docker history ubuntu:18.04 IMAGE CREATED CREATED BY SIZE d27b9ffc5667 13 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) CMD ["/bin/bash"] 0B <missing> 13 days ago /bin/sh -c mkdir -p /run/systemd && echo 'do… 7B <missing> 13 days ago /bin/sh -c set -xe && echo '#!/bin/sh' > /… 745B <missing> 13 days ago /bin/sh -c [ -z "$(apt-get indextargets)" ] 987kB <missing> 13 days ago /bin/sh -c #(nop) ADD file:0b40d881e3e00d68d… 63.2MB

So both commands give you the information similar to the Dockerfile content. But you have to admit that it is pretty complex and not very user-friendly. Fortunately, some tools might help you inspect Docker images. Start with checking out dive

It gives you a good view of each Docker image layer with information on what and where something has changed. The above example shows the layers of Ubuntu:18.04 image and corresponding changes to the files in that layer.

All those commands and tools should give you more confidence in order to decide whether it is safe to run a certain image.

Scan and sign

Usually, you do not have time to manually inspect images and check whether they are safe or not. Especially when you do not look for some malicious code but check for some well-known threats and vulnerabilities. This also applies when you build a container by yourself. In that case, you are probably sure that there is no malicious application or package installed, but still, you have to use some base image that may introduce some vulnerabilities. So again, there are multiple tools to help developers and operators check images.

The first two of them are focused on scanning images for Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE). All those scanners work pretty similarly – scanning images using external data with known vulnerabilities. It may come from OS vendors or non-OS data like NVD (National Vulnerability Database). Results in most cases, depend on the fact which CVE databases are used and if they are up-to-date. So the final number of detected vulnerabilities may differ for different tools. The scan process itself simply analyzes the contents and creates a history of an image with the mentioned databases.

Below are some results from open source tools Clair created by CoreOS and Trivy developed by Aquasec.

$ clair-scanner ubuntu:18.04

$ clair-scanner ubuntu:18.04

2020/07/22 10:10:02 [INFO] ▶ Start clair-scanner

2020/07/22 10:10:04 [INFO] ▶ Server listening on port 9279

2020/07/22 10:10:04 [INFO] ▶ Analyzing e86dffecb5a4284ee30b1905fef785336d438013826e4ee74a8fe7d65d95ee8f

2020/07/22 10:10:07 [INFO] ▶ Analyzing 7ff84cfee7ab786ad59579706ae939450d999e578c6c3a367112d6ab30b5b9b4

2020/07/22 10:10:07 [INFO] ▶ Analyzing 940667a71e178496a1794c59d07723a6f6716f398acade85b4673eb204156c79

2020/07/22 10:10:07 [INFO] ▶ Analyzing 22367c56cc00ec42fb1d0ca208772395cc3ea1e842fc5122ff568589e2c4e54e

2020/07/22 10:10:07 [WARN] ▶ Image [ubuntu:18.04] contains 39 total vulnerabilities

2020/07/22 10:10:07 [ERRO] ▶ Image [ubuntu:18.04] contains 39 unapproved vulnerabilities

+------------+-----------------------+-------+-------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------+

| STATUS | CVE SEVERITY | PKG | PACKAGE VERSION | CVE DESCRIPTION |

+------------+-----------------------+-------+-------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------+

(...)

+------------+-----------------------+-------+-------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------+

| Unapproved | Medium CVE-2020-10543 | perl | 5.26.1-6ubuntu0.3 | Perl before 5.30.3 on 32-bit platforms allows a heap-based |

| | | | | buffer overflow because nested regular expression |

| | | | | quantifiers have an integer overflow. An application |

| | | | | written in Perl would only be vulnerable to this flaw if |

| | | | | it evaluates regular expressions supplied by the attacker. |

| | | | | Evaluating regular expressions in this fashion is known |

| | | | | to be dangerous since the regular expression engine does |

| | | | | not protect against denial of service attacks in this |

| | | | | usage scenario. Additionally, the target system needs a |

| | | | | sufficient amount of memory to allocate partial expansions |

| | | | | of the nested quantifiers prior to the overflow occurring. |

| | | | | This requirement is unlikely to be met on 64bit systems.] |

| | | | | http://people.ubuntu.com/~ubuntu-security/cve/CVE-2020-10543 |

+------------+-----------------------+-------+-------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------+

| Unapproved | Medium CVE-2018-11236 | glibc | 2.27-3ubuntu1 | stdlib/canonicalize.c in the GNU C Library (aka glibc |

| | | | | or libc6) 2.27 and earlier, when processing very |

| | | | | long pathname arguments to the realpath function, |

| | | | | could encounter an integer overflow on 32-bit |

| | | | | architectures, leading to a stack-based buffer |

| | | | | overflow and, potentially, arbitrary code execution. |

| | | | | http://people.ubuntu.com/~ubuntu-security/cve/CVE-2018-11236 |

(...)

+------------+-----------------------+-------+-------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------+

| Unapproved | Low CVE-2019-18276 | bash | 4.4.18-2ubuntu1.2 | An issue was discovered in disable_priv_mode in shell.c |

| | | | | in GNU Bash through 5.0 patch 11. By default, if Bash is |

| | | | | run with its effective UID not equal to its real UID, it |

| | | | | will drop privileges by setting its effective UID to its |

| | | | | real UID. However, it does so incorrectly. On Linux and |

| | | | | other systems that support "saved UID" functionality, |

| | | | | the saved UID is not dropped. An attacker with command |

| | | | | execution in the shell can use "enable -f" for runtime |

| | | | | loading of a new builtin, which can be a shared object that |

| | | | | calls setuid() and therefore regains privileges. However, |

| | | | | binaries running with an effective UID of 0 are unaffected. |

| | | | | http://people.ubuntu.com/~ubuntu-security/cve/CVE-2019-18276 |

+------------+-----------------------+-------+-------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------+

As mentioned above, both results are subtly different, but it is okay. If you investigate issues reported by Trivy, you will see duplicates, and in the end, both results are the same. But it is not the rule, and usually, they differ.

Based on the above reports, you should be sure if it is safe to use that particular image or not. By inspecting the image, you ensure what is running there, and thanks to the scanner, you are guaranteed about any known CVE. But it is important to underline that those vulnerabilities have to be known. In case of some new threats, you should schedule a regular scan, e.g., every week. In some of the Docker registries, this can be very easily configured, or you can use your CI/CD to run scheduled pipelines. It is also a good idea to send some notification in case of any High Severity vulnerability is found.

Active image scanning

All the above methods are passive, which means they do not actively scan or verify a running container. It was just a static analysis and scan of the image. If you want to be super secure, then you can simply add this live runtime scanner. An example of such a tool is Falco . It is an open-source project started by SysDig and now developed as CNCF Incubating Project. An extremely useful advantage provided by Falco comes to scanning for any abnormal behavior in your container. Besides, it has a built-in analyzer for Kubernetes Audit events. So taking both features together, this is a quite powerful tool to analyze and keep an eye on running containers in real-time. Below there is a quick setup of Falco with the Kubernetes cluster.

First of all, you have to run Falco. You can, of course, deploy it on Kubernetes or use the standalone version. Per the documentation, the most secure way is to run it separated from the Kubernetes cluster to provide isolation in case of a hacker attack. For testing purposes, we will do it in a different way and deploy it onto Kubernetes using Helm .

The setup is quite simple. First, we have to add the helm repository with a falco chart and simply install it. Please note that nginx pod is used for testing purposes and is not a part of Falco.

$ helm repo add falcosecurity https://falcosecurity.github.io/charts

$ helm repo update

$ helm install falco falcosecurity/falco

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

falco-qq8zx 1/1 Running 0 23m

falco-t5glj 1/1 Running 0 23m

falco-w2krg 1/1 Running 0 23m

nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg 1/1 Running 0 25m

And that is it. Now let’s test that. Falco comes with already predefined rules, so we can, for example, try to exec into some pod and view sensitive data from files. We will use the mentioned nginx pod.

$ kubectl exec -it nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg /bin/bash

root@nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg:/# echo "Knock, knock!"

Knock, knock!

root@nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg:/# cat /etc/shadow > /dev/null

root@nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg:/# exit

Now we should check the logs from the falco pod which runs on the same node as our nginx.

$ kubectl logs falco-w2krg

* Setting up /usr/src links from host

* Running falco-driver-loader with: driver=module, compile=y...

* Unloading falco module, if present

(...)

17:07:53.445726385: Notice A shell was spawned in a container with an attached terminal (user=root k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc shell=bash parent=runc cmdline=bash terminal=34816 container_id=b17be5f70cdc image=<NA>) k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc

17:08:39.377051667: Warning Sensitive file opened for reading by non-trusted program (user=root program=cat command=cat /etc/shadow file=/etc/shadow parent=bash gparent=<NA> ggparent=<NA> gggparent=<NA> container_id=b17be5f70cdc image=<NA>) k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc

Great, there are nice log messages about exec and reading sensitive file incidents with some additional information. The good thing is that you can easily add your own rules.

$ cat custom_rule.yaml

customRules:

example-rules.yaml: |-

- rule: shell_in_container

desc: notice shell activity within a container

condition: container.id != host and proc.name = bash

output: TEST shell in a container (user=%user.name)

priority: WARNING

To apply them you have to update the helm chart again.

$ helm install falco -f custom_rule.yaml falcosecurity/falco

$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

falco-7qnn8 1/1 Running 0 6m21s

falco-c54nl 1/1 Running 0 6m3s

falco-k859g 1/1 Running 0 6m11s

nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg 1/1 Running 0 45m

Now we can repeat the procedure and see if there is something more in the logs.

$ kubectl exec -it nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg /bin/bash

root@nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg:/# echo "Knock, knock!"

Knock, knock!

root@nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg:/# cat /etc/shadow > /dev/null

root@nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg:/# exit

$ kubectl logs falco-7qnn8

* Setting up /usr/src links from host

* Running falco-driver-loader with: driver=module, compile=yes, download=yes

* Unloading falco module, if present

(...)

17:33:35.547831851: Notice A shell was spawned in a container with an attached terminal (user=root k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc shell=bash parent=runc cmdline=bash terminal=34816 container_id=b17be5f70cdc image=<NA>) k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc

17:33:35.551194695: Warning TEST shell in a container (user=root) k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc

(...)

17:33:40.327820806: Warning Sensitive file opened for reading by non-trusted program (user=root program=cat command=cat /etc/shadow file=/etc/shadow parent=bash gparent=<NA> ggparent=<NA> gggparent=<NA> container_id=b17be5f70cdc image=<NA>) k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc k8s.ns=default k8s.pod=nginx-6db489d4b7-6pvjg container=b17be5f70cdc

You can see a new message is there. You can add more rules and customize falco to your needs. We encourage setting up gRPC and then using falco-exporter to integrate it with Prometheus to easily monitor any security incident. In addition, you may also configure falco to support Kubernetes audit events.

Is it enough? You have inspected and scanned your image. You deployed a runtime scanner to keep an eye on the running containers. But none of those methods guarantee that the image you have just pulled or started is the same you wanted to run. What if someone injected there some malicious code and you did not notice? In order to defend against such an attack, you have to somehow securely and confidently identify the image. There has to be some tool that guarantees us such confidence… and there is one!

The UpdateFramework and Notary

The key element that helps and in fact solves many of those concerns is The Update Framework (TUF) that describes the update system as “secure” if:

- “it knows about the latest available updates in a timely manner,

- any files it downloads are the correct files, and,

- no harm results from checking or downloading files.”

(source: https://theupdateframework.github.io/security.html )

There are four principles defined by the framework that make it almost impossible to make a successful attack on such an update system.

1. The first principle is responsibility separation. In other words, there are a few different roles defined (that are used by e.g., the user or server) that are able to do different actions and use different keys for that purpose.

2. The next one is the multi-signature trust. This simply says that you need a fixed number of signatures which has to come together to perform certain actions, e.g., two developers using their keys to agree that a specific package is valid.

3. The third principle is explicit and implicit revocation. Explicit means that some parties come together and revoke another key, whereas implicit is when e.g., after some time, the repository may automatically revoke signing keys.

4. The last principle is to minimize individual key and role risks. As it says, the goal is to minimize the expected damage which can be defined by the probability of the event happening and its impact. So if there is a root role with a high impact on the system, the key it uses is kept offline.

The idea of TUF is to create and manage a set of metadata (signed by corresponding roles) that provide general information about the valid state of the repository at a specified time.

The next question is: How can Docker use this update framework, and what does it mean to you and me? First of all, Docker already uses it in the Content Trust, which definition seems to answer our first question about image correctness. As per documentation:

“Content trust provides the ability to use digital signatures for data sent to and received from remote Docker registries. These signatures allow client-side verification of the integrity and publisher of specific image tags.”

(source: https://docs.docker.com/engine/security/trust/content_trust )

To be more precise, Content Trust does not use TUF directly. Instead, it uses Notary, a tool created by Docker, which is an opinionated implementation of TUF. It keeps the TUF principles, so there are five roles (with corresponding keys), same as TUF defined, so we have:

· a root role – it uses the most important key that is used to sign the root metadata, which specifies other roles, so it is strongly advised to keep it secure offline;

· a snapshot role – this role signs snapshot metadata that contains information about file names, sizes, hashes of other (root, target and delegation) metadata files, so it ensures users about their integrity. It can be held by owner/admin or Notary service itself;

· a timestamp role – using timestamp key Notary signs metadata file which guarantee the freshness of the trusted collection, because of short expiration time. Due to that fact it is kept by Notary service to automatically regenerate when it is outdated;

· a targets role – it uses the targets key to sign the targets metadata file, with information about files in the collection (filenames, sizes and corresponding hashes) and it should be used to verify the integrity of the files inside the collection. The other usage of the targets key is to delegate trust to other peers using delegation roles.

· a delegation role – which is pretty similar to the targets role but instead of the whole content of the repository those keys ensure integrity of some (or sometimes all) of the actual content. They also can be used to delegate trust to other collaborators via lower level delegation roles.

All this metadata can be pulled or pushed to the Notary service. There are two components in the Notary service – server and signer. The server is responsible for storing the metadata (those files generated by the TUF framework underneath) for trusted collections in an associated database, generating the timestamp metadata, and the most important validating any uploaded metadata.

Notary signer stores private keys (this way they are not kept in the Notary server) and in case of a request from the Notary server it signs metadata for it. In addition, there is a Notary CLI that helps you to manage trusted collections and supports Content Trust with additional functionality. The basic interaction between client, server, and service can be described as: When the client wants to upload new metadata, after authentication (if required) metadata is validated by the server, which generates timestamp metadata (and sometimes snapshot based on what has changed) and sends it to the Notary signer for signing. After that server stores the client metadata, timestamp, and snapshot metadata which ensures that client files are the most recent and valid.

Let’s check how it works. First, run an unsigned image with Docker Content Trust (DCT) disabled. Everything works fine, so we can simply run our image v1:

$ docker run mirograpeup/hello:v1

Unable to find image 'mirograpeup/hello:v1' locally

v1: Pulling from mirograpeup/hello

Digest: sha256:be202781edb5aa6c322ec19d04aba6938b46e136a09512feed26659fb404d637

Status: Downloaded newer image for mirograpeup/hello:v1

Hello World folks!!!

Now we can check how it goes with DCT enabled. First, let’s see what happens when we want to run v2 (which is not signed as well):

$ export DOCKER_CONTENT_TRUST=1

$ docker run mirograpeup/hello:v2

docker: Error: remote trust data does not exist for docker.io/mirograpeup/hello: notary.docker.io does not have trust data for docker.io/mirograpeup/hello.

apiVersion: v1

See 'docker run --help'.

The error above is obvious – we did not specify the trust data/signatures for that image, so it fails to run. To sign the image, you have to push it to the remote repository.

$ docker push mirograpeup/hello:v2

The push refers to repository [docker.io/mirograpeup/hello]

c71acc1231cb: Layer already exists

v2: digest: sha256:be202781edb5aa6c322ec19d04aba6938b46e136a09512feed26659fb404d637 size: 524

Signing and pushing trust metadata

Enter passphrase for root key with ID 1d3d9a4:

Enter passphrase for new repository key with ID 5a9ff85:

Repeat passphrase for new repository key with ID 5a9ff85:

Finished initializing "docker.io/mirograpeup/hello"

Successfully signed docker.io/mirograpeup/hello:v2

For the first time, docker will ask you for the corresponding passphrases for the root key and repository if needed. After that, your image is signed, and we can check again if v1 or v2 can run.

$ docker run mirograpeup/hello:v1

docker: No valid trust data for v1.

See 'docker run --help'.

$ docker run mirograpeup/hello:v2

Hello World folks!!!

So it works well. You can see that it is not allowed to run unsigned images when DCT is enabled and that during the push all the signing process is done automatically. In the end, even though the process itself is a little bit complicated, you can very easily push images to the Docker repository and be sure that it is always the image you intended to run. One drawback of the DCT is that it is not supported in Kubernetes by default. You are able to work around that with admission plugins but it requires additional work.

Registry

We spoke a lot about containers security and how to run them without a headache. But besides that, you have to secure your container registry. First of all, you need to decide whether to use a hosted (e.g., Docker Hub) or on-prem registry.

One good thing about a hosted registry is that it should support (at least Docker Hub does) the Docker Content Trust by default and you just have to enable that on the client side. If you want that to be supported in the on-prem registry then you have to deploy the Notary server and configure that properly on the client side.

On the other hand, the Docker Hub does not provide image scanning and in the on-prem registries, it is usually a standard to provide such ability. Plus in most cases, those solutions support more than one image scanner. So you can choose which scanner you want to run. In some cases, like in Harbor, you are allowed to configure automatically scheduled tests and you can set up some notifications if needed. So it is a very nice thing that the on-prem registry is not worse and sometimes offers more than a free Docker Hub registry which comes with few limitations.

In addition, you have much more control over the on-prem registry. You can have a super-admin account and see all the images and statistics. But you have to maintain it and make sure it will be always up and running. Still, many companies prevent use of external registries - so in that case, you have no choice.

Whatever you choose, always make sure to use TLS communication. If your on-prem registry uses self-signed or signed by company root CA, certificates, then you have to configure Docker in Kubernetes properly. You can specify the insecure-registries option in the Docker daemon, but it may end up with fallback to HTTP which is not what we tried to prevent in the first place. A more secure option is to provide the certificates to the Docker daemon:

cp domain.crt /etc/docker/certs.d/mydomain.com:5000/ca.crt

Private registry

Also, if you want to use a private registry, you will have to provide the credentials or cache (manually load) the image to each worker node. Please note to force cached images to be used you need to block the imagePullPolicy: Always . When it comes to providing credentials, you basically have two options.

Configure Nodes

Prepare the proper docker config.json:

{

"auths": {

"https://index.docker.io/v1/": {

"username": "xxxxxxxx"

"password": "xxxxxxxx"

"email": "xxxxxxxx"

"auth": "<base64-encoded-‘username:password’>"

}

}

}

And copy that to each worker node to the kubelet configuration directory. It is usually /var/lib/kubelet, so for a single worker it would be:

$ scp config.json root@worker-node:/var/lib/kubelet/config.json

Use ImagePullSecrets

The easiest way is to use the built-in mechanism in the Kubernetes secrets:

kubectl create secret docker-registry <secret-name> \

--docker-server=<your-registry-server> \

--docker-username=<your-name> \

--docker-password=<your-password> \

--docker-email=<your-email>

or you may create a secret by providing a YAML file with the base64 encoded docker config.json:

{

"auths": {

"https://index.docker.io/v1/": {

"username": "xxxxxxxx"

"password": "xxxxxxxx"

"email": "xxxxxxxx"

"auth": "<base64-encoded-‘username:password’>"

}

}

}

secret.yml (please note the type has to be kubernetes.io/dockerconfigjson and the data should be placed under .dockerconfigjson):

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: <secret-name>

namespace: <namespace-name>

data:

.dockerconfigjson: <base64-encoded-config-json-file>

type: kubernetes.io/dockerconfigjson

Adding the above secret, you have to keep in mind that it works only in the specified namespace, and anyone in that namespace may be able to read that. So you have to be careful who is allowed to use your namespace/cluster. Now, if you want to use this secret, you simply have to put it in the Pod spec imagePullSecrets property:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: private-reg

spec:

containers:

- name: private-reg-container

image: <your-private-image>

imagePullSecrets:

- name: <your-secret-name>

Container security checks

If you want to be even more secure than you can run some additional tests to check your setup. In that case, the Docker security is the thing you want to check. In order to do that, you can use Docker Bench Security. It will scan your runtime to find any issues or insecure configurations. The easiest way is to run it as a pod inside your cluster. You have to mount a few directories from the worker node and run this pod as root, so make sure you know what you are doing. The below example shows how the Pod is configured if your worker runs on Ubuntu (there are some different mount directories needed on different operating systems).

cat docker-bench.yml

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: docker-bench

spec:

hostPID: true

hostIPC: true

hostNetwork: true

securityContext:

runAsUser: 0

containers:

- name: docker-bench

image: docker/docker-bench-security

securityContext:

privileged: true

capabilities:

add: ["AUDIT_CONTROL"]

volumeMounts:

- name: etc

mountPath: /etc

readOnly: true

- name: libsystemd

mountPath: /lib/systemd/system

readOnly: true

- name: usrbincontainerd

mountPath: /usr/bin/containerd

readOnly: true

- name: usrbinrunc

mountPath: /usr/bin/runc

readOnly: true

- name: usrlibsystemd

mountPath: /usr/lib/systemd

readOnly: true

- name: varlib

mountPath: /var/lib

readOnly: true

- name: dockersock

mountPath: /var/run/docker.sock

readOnly: true

volumes:

- name: etc

hostPath:

path: /etc

- name: libsystemd

hostPath:

path: /lib/systemd/system

- name: usrbincontainerd

hostPath:

path: /usr/bin/containerd

- name: usrbinrunc

hostPath:

path: /usr/bin/runc

- name: usrlibsystemd

hostPath:

path: /usr/lib/systemd

- name: varlib

hostPath:

path: /var/lib

- name: dockersock

hostPath:

path: /var/run/docker.sock

type: Socket

kubectl apply -f docker-bench.yml

kubectl logs docker-bench -f

# ------------------------------------------------------------------------------

# Docker Bench for Security v1.3.4

#

# Docker, Inc. (c) 2015-

#

# Checks for dozens of common best-practices around deploying Docker containers in production.

# Inspired by the CIS Docker Community Edition Benchmark v1.1.0.

# ------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Initializing Sun Sep 13 22:41:02 UTC 2020

[INFO] 1 - Host Configuration

[WARN] 1.1 - Ensure a separate partition for containers has been created

[NOTE] 1.2 - Ensure the container host has been Hardened

[INFO] 1.3 - Ensure Docker is up to date

[INFO] * Using 18.09.5, verify is it up to date as deemed necessary

[INFO] * Your operating system vendor may provide support and security maintenance for Docker

[INFO] 1.4 - Ensure only trusted users are allowed to control Docker daemon

[INFO] * docker:x:998

[WARN] 1.5 - Ensure auditing is configured for the Docker daemon

[WARN] 1.6 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - /var/lib/docker

[WARN] 1.7 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - /etc/docker

[WARN] 1.8 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - docker.service

[INFO] 1.9 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - docker.socket

[INFO] * File not found

[WARN] 1.10 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - /etc/default/docker

[INFO] 1.11 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - /etc/docker/daemon.json

[INFO] * File not found

[INFO] 1.12 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - /usr/bin/docker-containerd

[INFO] * File not found

[INFO] 1.13 - Ensure auditing is configured for Docker files and directories - /usr/bin/docker-runc

[INFO] * File not found

[INFO] 2 - Docker daemon configuration

[WARN] 2.1 - Ensure network traffic is restricted between containers on the default bridge

[PASS] 2.2 - Ensure the logging level is set to 'info'

[WARN] 2.3 - Ensure Docker is allowed to make changes to iptables

[PASS] 2.4 - Ensure insecure registries are not used

[PASS] 2.5 - Ensure aufs storage driver is not used

[INFO] 2.6 - Ensure TLS authentication for Docker daemon is configured

(...)

After completing these steps, you can check the logs from the Pod to see the full output from Docker Bench Security and act on any warning you see there. The task is quite demanding but gives you the most secure Docker runtime. Please note sometimes you have to leave a few warnings in order to keep everything working. Then you still have an option to provide more security using Kubernetes configuration and resources, but this is a topic for a separate article.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.