How to automate operationalization of Machine Learning apps - an introduction to Metaflow

In this article, we briefly highlight the features of Metaflow, a tool designed to help data scientists operationalize machine learning applications.

Introduction to machine learning operationalization

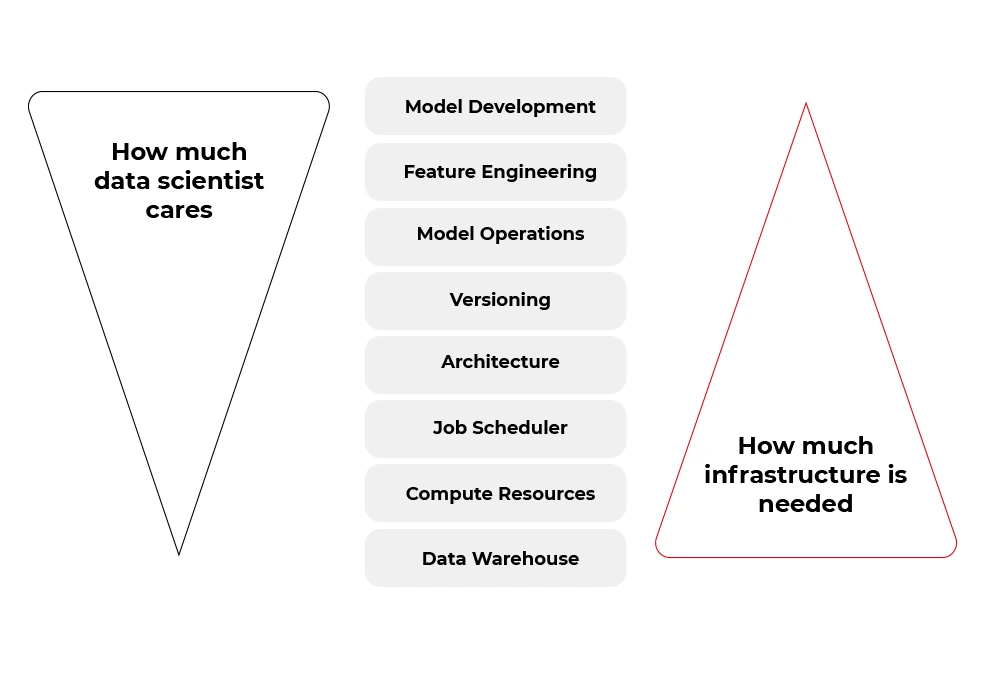

Data-driven projects become the main area of focus for a fast-growing number of companies. The magic has started to happen a couple of years ago thanks to sophisticated machine learning algorithms, especially those based on deep learning. Nowadays, most companies want to use that magic to create software with a breeze of intelligence. In short, there are two kinds of skills required to become a data wizard:

Research skills - understood as the ability to find typical and non-obvious solutions for data-related tasks, specifically extraction of knowledge from data in the context of a business domain. This job is typically done by data scientists but is strongly related to machine learning, data mining, and big data.

Software engineering skills - because the matter in which these wonderful things can exist is software. No matter what we do, there are some rules of the modern software development process that help a lot to be successful in business. By analogy with intelligent mind and body, software also requires hardware infrastructure to function.

People tend to specialize, so over time, a natural division has emerged between those responsible for data analysis and those responsible for transforming prototypes into functional and scalable products. That shouldn't be surprising, as creating rules for a set of machines in the cloud is a far different job from the work of a data detective.

Fortunately, many of the tasks from the second bucket (infrastructure and software) can be automated. Some tools aim to boost the productivity of data scientists by allowing them to focus on the work of a data detective rather than on the productionization of solutions. And one of these tools is called Metaflow.

If you want to focus more on data science , less on engineering, but be able to scale every aspect of your work with no pain, you should take a look at how is Metaflow designed.

A Review of Metaflow

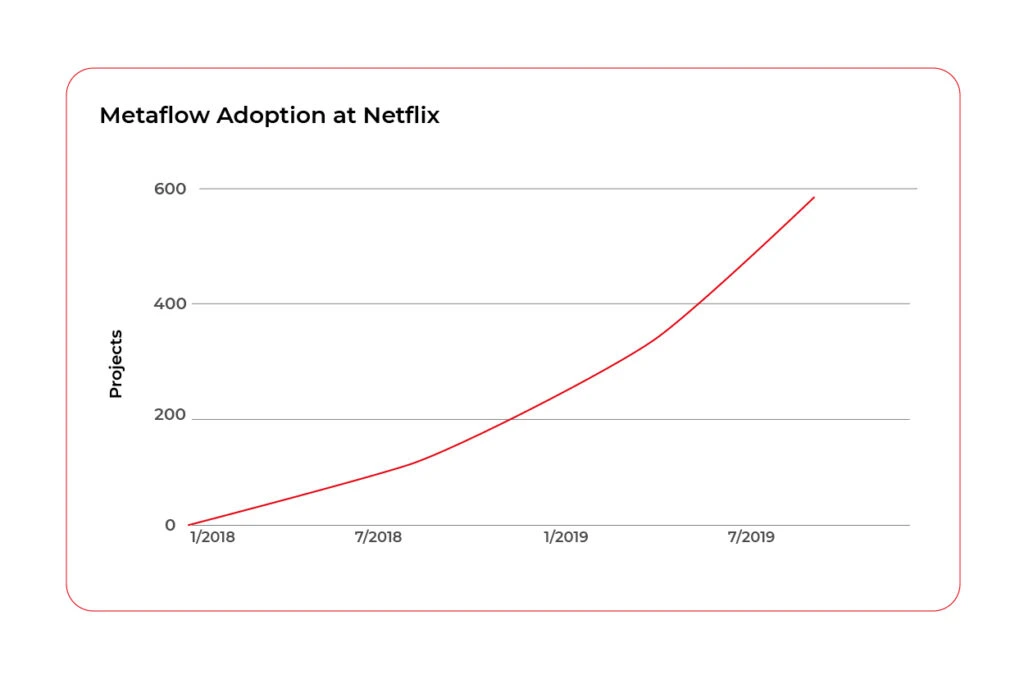

Metaflow is a framework for building and managing data science projects developed by Netflix. Before it was released as an open-source project in December 2019, they used it to boost the productivity of their data science teams working on a wide variety of projects from classical statistics to state-of-the-art deep learning.

The Metaflow library has Python and R API, however, almost 85% of the source code from the official repository (https://github.com/Netflix/metaflow) is written in Python. Also, separate documentation for R and Python is available.

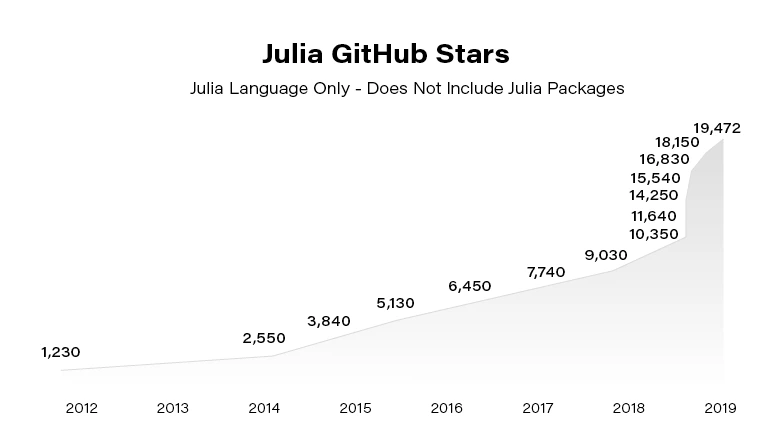

At the time this article is written (July 2021), the official repository of the Metaflow has 4,5 k stars, above 380 forks, and 36 contributors, so it can be assumed as a mature framework.

“Metaflow is built for data scientists, not just for machines”

That sentence got attention when you visit the official website of the project ( https://metaflow.org/ ). Indeed, these are not empty words. Metaflow takes care of versioning, dependency management, computing resources, hyperparameters, parallelization, communication with AWS stack, and much more. You can truly focus on the core part of your data-related work and let Metaflow do all these things using just very expressive decorators.

Metaflow - core features

The list below explains the key features that make Metaflow such a wonderful tool for data scientists, especially for those who wish to remain ignorant in other areas.

- Abstraction over infrastructure. Metaflow provides a layer of abstraction over the hardware infrastructure available, cloud stack in particular. That’s why this tool is sometimes called a unified API to the infrastructure stack.

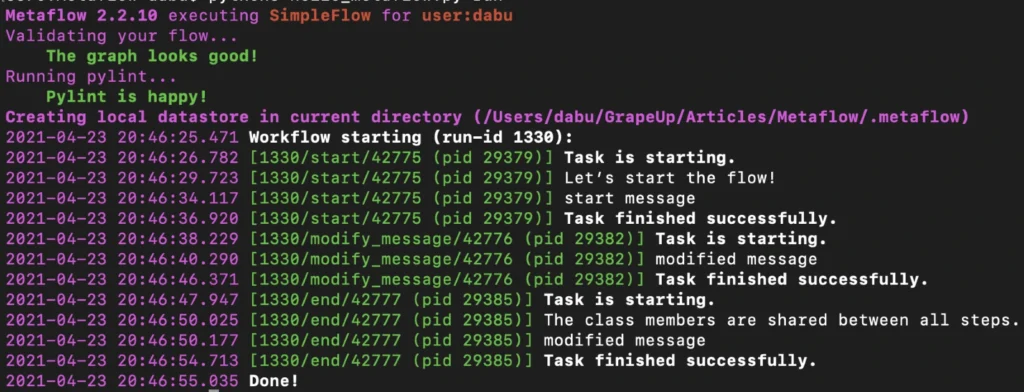

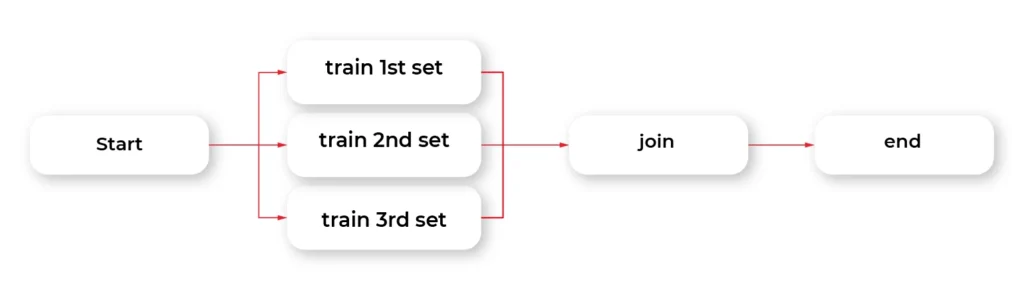

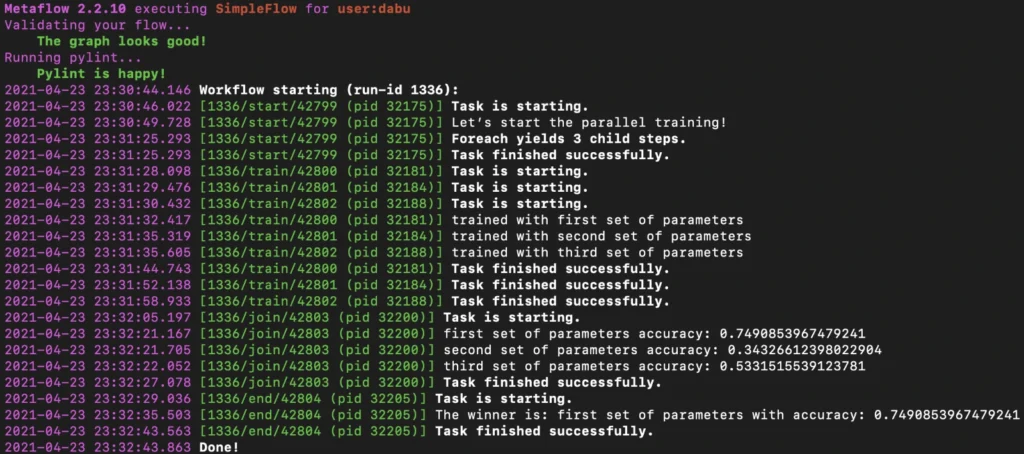

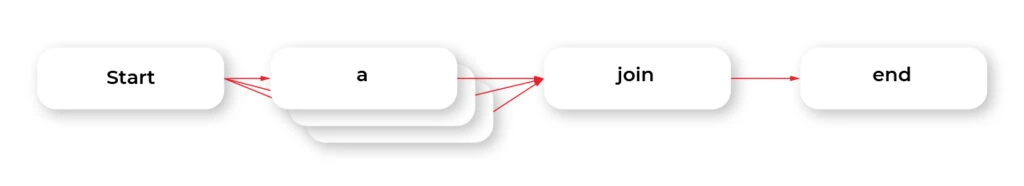

- Data pipeline organization. The framework represents the data flow as a directed acyclic graph. Each node in the graph, also called step, contains some code to run wrapped in a function with @step decorator.

@step

def get_lat_long_features(self):

self.features = coord_features(self.data, self.features)

self.next(self.add_categorical_features)

The nodes on each level of the graph can be computed in parallel, but the state of the graph between levels must be synchronized and stored somewhere (cached) – so we have very good asynchronous data pipeline architecture.

This approach facilitates debugging, enhances the performance of the pipeline, and allows us completely separate the steps so that we can run one step locally and the next one in the cloud if, for instance, the step requires solving large matrices. The disadvantage of that approach is that salient failures may happen without proper programming discipline.

- Versioning. Tracking versions of our machine learning models can be a challenging task. Metaflow can help here. The execution of each step of the graph (data, code, and parameters) is hashed and stored, and you can access logged data later, using client API.

- Containerization. Each step is run in a separate environment. We can specify conda libraries in each container using

@condadecorator as shown below. It can be a very useful feature under some circumstances.

@conda(libraries={"scikit-learn": "0.19.2"})

@step

def fit(self):

...

- Scalability. With the help of

@batchand@resourcesdecorators, we can simply command AWS Batch to spawn a container on ECS for the selected Metaflow step. If individual steps take long enough, the overhead of spawning the containers should become irrelevant.

@batch(cpu=1, memory=500)

@step

def hello(self):

...

- Hybrid runs. We can run one step locally and another compute-intensive step on the cloud and swap between these two modes very easily.

- Error handling. Metaflow’s

@retrydecorator can be used to set the number of retries if the step fails. Any error raised during execution can be handled by@catchdecorator. The@timeoutdecorator can be used to limit long-running jobs especially in expensive environments (for example with GPGPUs).

@catch(var="compute_failed")

@retry

@step

def statistics(self):

...

- Namespaces. An isolated production namespace helps to keep production results separate from experimental runs of the same project running concurrently. This feature is very useful in bigger projects where more people is involved in development and deployment processes.

from metaflow import Flow, namespace

namespace("user:will")

run = Flow("PredictionFlow").latest_run

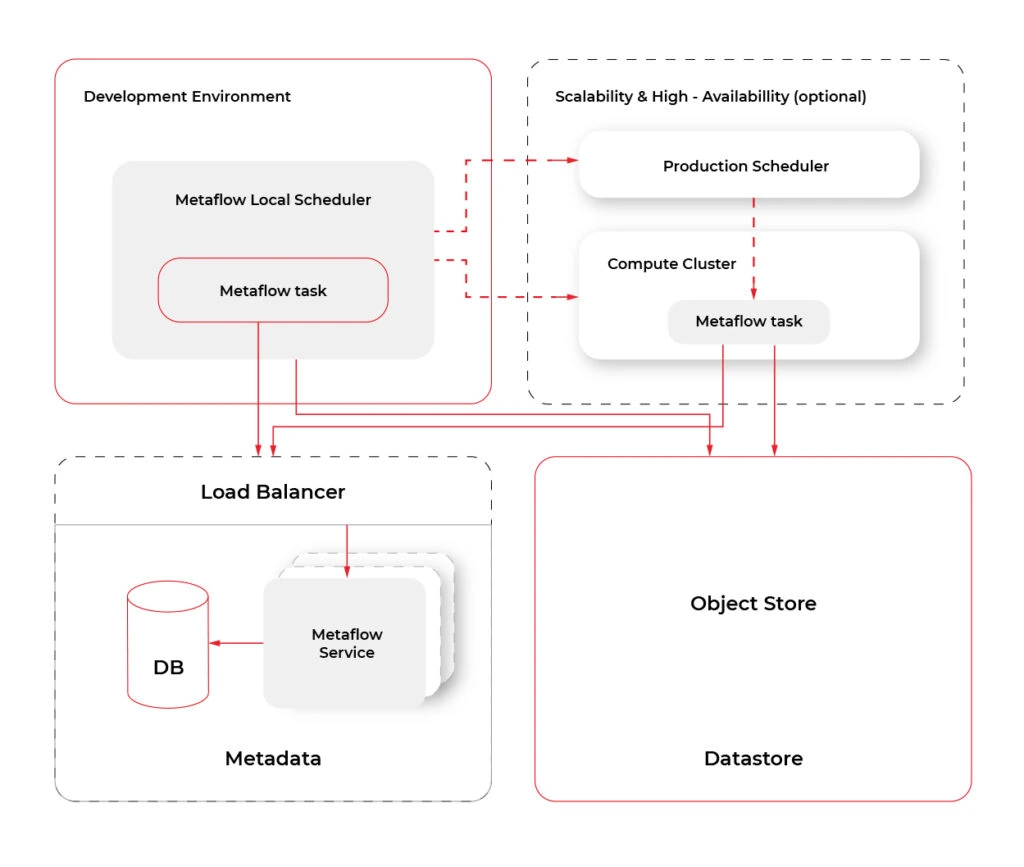

- Cloud Computing . Metaflow, by default, works in the local mode . However, the shared mode releases the true power of Metaflow. At the moment of writing, Metaflow is tightly and well coupled to AWS services like CloudFormation, EC2, S3, Batch, DynamoDB, Sagemaker, VPC Networking, Lamba, CloudWatch, Step Functions and more. There are plans to add more cloud providers in the future. The diagram below shows an overview of services used by Metaflow.

Metaflow - missing features

Metaflow does not solve all problems of data science projects. It’s a pity that there is only one cloud provider available, but maybe it will change in the future. Model serving in production could be also a really useful feature. Competitive tools like MLFlow or Apache AirFlow are more popular and better documented. Metaflow lacks a UI that would make metadata, logging, and tracking more accessible to developers. All this does not change the fact that Metaflow offers a unique and right approach, so just cannot be overlooked.

Conclusions

If you think Metaflow is just another tool for MLOps , you may be surprised. Metaflow offers data scientists a very comfortable workflow abstracting them from all low levels of that stuff. However, don't expect the current version of Metaflow to be perfect because Metaflow is young and still actively developed. However, the foundations are solid, and it has proven to be very successful at Netflix and outside of it many times.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.