How to get effective computing services: AWS Lambda

In the modern world, we are constantly faced with the need not only to develop applications but also to provide and maintain an environment for them. Writing scalable, fault-tolerant, and responsive programs is hard, and on top of that, you’re expected to know exactly how many servers, CPUs, and how much memory your code will need to run – especially when running in the Cloud. Also, developing cloud native applications and microservice architectures make our infrastructure more and more complicated every time.

So, how not worry about underlying infrastructure while deploying applications? How do get easy-to-use and manage computing services? The answer is in serverless applications and AWS Lambda in particular.

What you will find in this article:

- What is Serverless and what we can use that for?

- Introduction to AWS Lambda

- Role of AWS Lambda in Serverless applications

- Coding and managing AWS Lambda function

- Some tips about working with AWS Lambda function

What is serverless?

Serverless computing is a cloud computing execution model in which the cloud provider allocates machine resources on-demand, taking care of the servers on behalf of their customers. Despite the name, it does not involve running code without servers, because code has to be executed somewhere eventually. The name “serverless computing” is used because the business or person that owns the system does not have to purchase, rent, or provision servers or virtual machines for the back-end code to run on. But with provided infrastructure and management you can focus on only writing code that serves your customers.

Software Engineers will not have to take care of operating system (OS) access control, OS patching, provisioning, right-sizing, scaling, and availability. By building your application on a serverless platform, the platform manages these responsibilities for you.

The main advantages of AWS Serverless tools are :

- No server management – You don’t have to provision or maintain any servers. There is no software or runtime to install or maintain.

- Flexible scaling – You can scale your application automatically.

- High availability – Serverless applications have built-in availability and fault tolerance.

- No idle capacity – You don't have to pay for idle capacity.

- Major languages are supported out of the box - AWS Serverless tools can be used to run Java, Node.js, Python, C#, Go, and even PowerShell.

- Out of the box security support

- Easy orchestration - applications can be built and updated quickly.

- Easy monitoring - you can write logs in your application and then import them to Log Management Tool.

Of course, using Serverless may also bring some drawbacks:

- Vendor lock-in - Your application is completely dependent on a third-party provider. You do not have full control of your application. Most likely, you cannot change your platform or provider without making significant changes to your application.

- Serverless (and microservice) architectures introduce additional overhead for function/microservice calls - There are no “local” operations; you cannot assume that two communicating functions are located on the same server.

- Debugging is more difficult - Debugging serverless functions is possible, but it's not a simple task, and it can eat up lots of time and resources.

Despite all the shortcomings, the serverless approach is constantly growing and becoming capable of more and more tasks. AWS takes care of more and more development and distribution of serverless services and applications. For example, AWS now provides not only Lambda functions(computing service), but also API Gateway(Proxy), SNS(messaging service), SQS(queue service), EventBridge(event bus service), and DynamoDB(NoSql database).

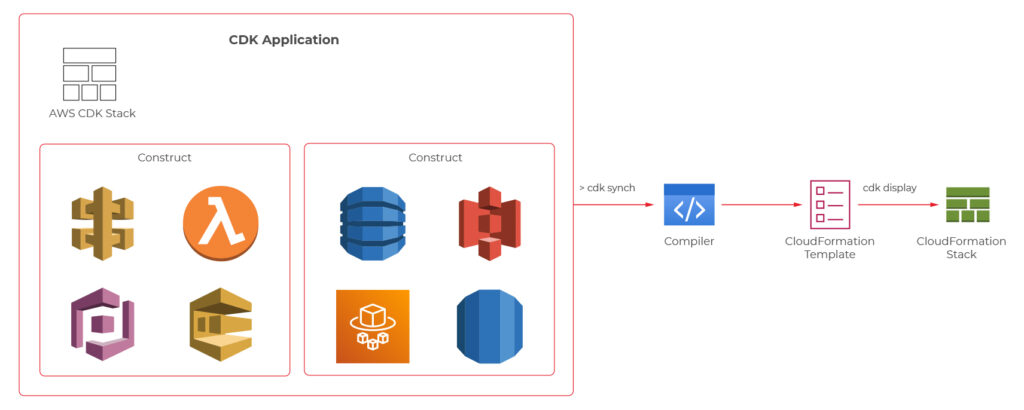

Moreover, AWS provides Serverless Framework which makes it easy to build computing applications using AWS Lambda. It scaffolds the project structure and takes care of deploying functions, so you can get started with your Lambda extremely quickly.

Also, AWS provides the specific framework to build complex serverless applications - Serverless Application Model (SAM). It is an abstraction to support and combine different types of AWS tools - Lambda, DynamoDB API Gateway, etc.

The biggest difference is that Serverless is written to deploy AWS Lambda functions to different providers. SAM on the other hand is an abstraction layer specifically for AWS using not only Lambda but also DynamoDB for storage and API Gateway for creating a serverless HTTP endpoint. Another difference is that SAM Local allows you to run some services, including Lambda functions, locally.

AWS Lambda concept

AWS Lambda is a Function-as-a-Service(FaaS) service from Amazon Web Services. It runs your code on a high-availability compute infrastructure and performs all of the administration of the compute resources, including server and operating system maintenance, capacity provisioning and automatic scaling, code monitoring, and logging.

AWS Lambda has the following conceptual elements:

- Function - A function is a resource that you can invoke to run your code in Lambda. A function has code to process the events that you pass into the function or that other AWS services send to the function. Also, you can add a qualifier to the function to specify a version or alias.

- Execution Environment - Lambda invokes your function in an execution environment, which provides a secure and isolated runtime environment. The execution environment manages the resources required to run your function. The execution environment also provides lifecycle support for the function's runtime. At a high level, each execution environment contains a dedicated copy of function code, Lambda layers selected for your function, the function runtime, and minimal Linux userland based on Amazon Linux.

- Deployment Package - You deploy your Lambda function code using a deployment package. AWS Lambda currently supports either a zip archive as a deployment package or a container image that is compatible with the Open Container Initiative (OCI) specification.

- Layer - A Lambda layer is a .zip file archive that contains libraries, a custom runtime, or other dependencies. You can use a layer to distribute a dependency to multiple functions. With Lambda Layers, you can configure your Lambda function to import additional code without including it in your deployment package. It is especially useful if you have several AWS Lambda functions that use the same set of functions or libraries. For example, in a layer, you can put some common code about logging, exception handling, and security check. A Lambda function that needs the code in there, should be configured to use the layer. When a Lambda function runs, the contents of the layer are extracted into the /opt folder in the Lambda runtime environment. The layer need not be restricted to the language of the Lambda function. Layers also have some limitations: each Lambda function may have only up to 5 layers configured and layer size is not allowed to be bigger than 250MB.

- Runtime - The runtime provides a language-specific environment that runs in an execution environment. The runtime relays invocation events, context information, and responses between Lambda and the function. AWS offers an increasing number of Lambda runtimes, which allow you to write your code in different versions of several programming languages. At the moment of this writing, AWS Lambda natively supports Java, Go, PowerShell, Node.js, C#, Python, and Ruby. You can use runtimes that Lambda provides, or build your own.

- Extension - Lambda extensions enable you to augment your functions. For example, you can use extensions to integrate your functions with your preferred monitoring, observability, security, and governance tools.

- Event - An event is a JSON-formatted document that contains data for a Lambda function to process. The runtime converts the event to an object and passes it to your function code.

- Trigger - A trigger is a resource or configuration that invokes a Lambda function. This includes AWS services that you can configure to invoke a function, applications that you develop, or some event source.

So, what exactly is behind AWS Lambda?

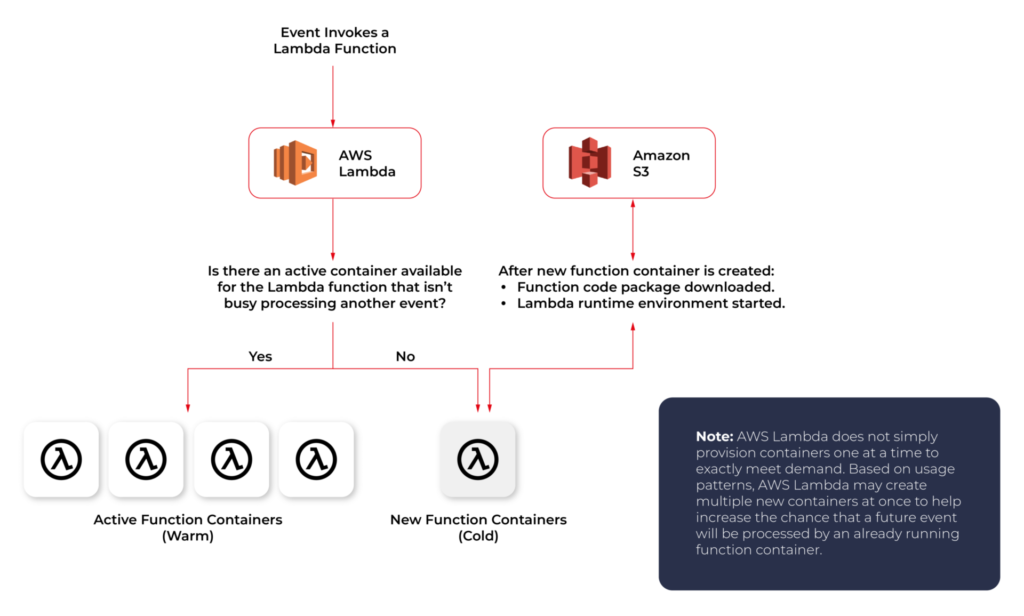

From an infrastructure standpoint, every AWS Lambda is part of a container running Amazon Linux (referenced as Function Container). The code files and assets you create for your AWS Lambda are called Function Code Package and are stored on an S3 bucket managed by AWS. Whenever a Lambda function is triggered, the Function Code Package is downloaded from the S3 bucket to the Function container and installed on its Lambda runtime environment. This process can be easily scaled, and multiple calls for a specific Lambda function can be performed without any trouble by the AWS infrastructure.

The Lambda service is divided into two control planes. The control plane is a master component responsible for making global decisions about provisioning, maintaining, and distributing a workload. A second plane is a data plane that controls the Invoke API that runs Lambda functions. When a Lambda function is invoked, the data plane allocates an execution environment to that function, chooses an existing execution environment that has already been set up for that function, then runs the function code in that environment.

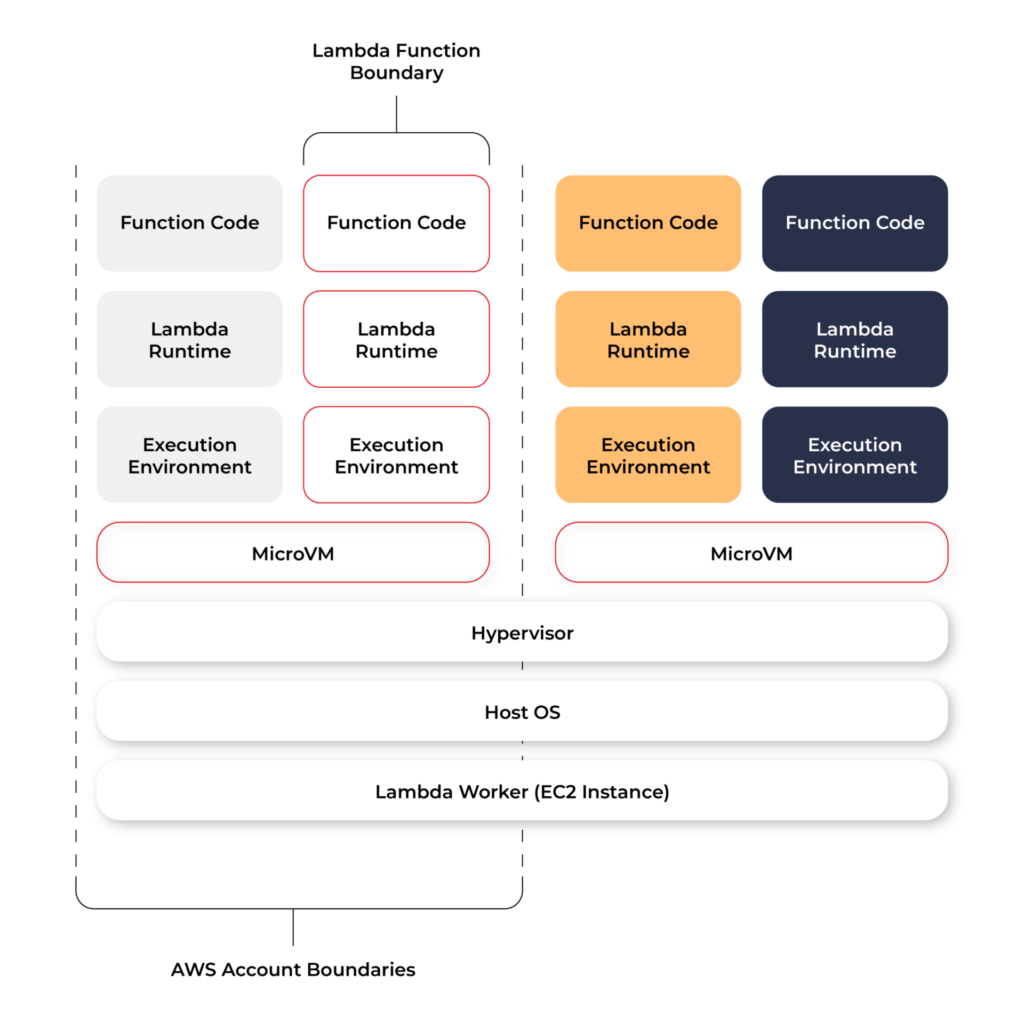

Each function runs in one or more dedicated execution environments that are used for the lifetime of the function and then destroyed. Each execution environment hosts one concurrent invocation but is reused in place across multiple serial invocations of the same function. Execution environments run on hardware virtualized virtual machines (microVMs). A micro VM is dedicated to an AWS account but can be reused by execution environments across functions within an account. MicroVMs are packed onto an AWS-owned and managed hardware platform (Lambda Workers). Execution environments are never shared across functions and microVMs are never shared across AWS accounts.

Even though Lambda execution environments are never reused across functions, a single execution environment can be reused for invoking the same function, potentially existing for hours before it is destroyed.

Each Lambda execution environment also includes a writeable file system, available at /tmp . This storage is not accessible to other execution environments. As with the process state, files are written to /tmp remain for the lifetime of the execution environment.

Cold start VS Warm start

When you call a Lambda Function, it follows the steps described above and executes the code. After finishing the execution, the Lambda Container stays available for a few minutes, before being terminated. This is called a Cold Start.

If you call the same function and the Lambda Container is still available (haven’t been terminated yet), AWS uses this container to execute your new call. This process of using active function containers is called Warm Container and it increases the response speed of your Lambda.

Role of AWS Lambda in serverless applications

There are a lot of use cases you can use AWS Lambda for, but there are killer cases for which Lambda is best suited:

- Operating serverless back-end

The web frontend can send requests to Lambda functions via API Gateway HTTPS endpoints. Lambda can handle the application logic and persist data to a fully-managed database service (RDS for relational, or DynamoDB for a non-relational database).

- Working with external services

If your application needs to request services from an external provider, there's generally no reason why the code for the site or the main application needs to handle the details of the request and the response. In fact, waiting for a response from an external source is one of the main causes of slowdowns in web-based services. If you hand requests for such things as credit authorization or inventory checks to an application running on AWS Lambda, your main program can continue with other elements of the transaction while it waits for a response from the Lambda function. This means that in many cases, a slow response from the provider will be hidden from your customers, since they will see the transaction proceeding, with the required data arriving and being processed before it closes.

- Near-realtime notifications

Any type of notifications, but particularly real-time, will find a use case with serverless Lambda. Once you create an SNS, you can set triggers that fire under certain policies. You can easily build a Lambda function to check log files from Cloudtrail or Cloudwatch. Lambda can search in the logs looking for specific events or log entries as they occur and send out notifications via SNS. You can also easily implement custom notification hooks to Slack or another system by calling its API endpoint within Lambda.

- Scheduled tasks and automated backups

Scheduled Lambda events are great for housekeeping within AWS accounts. Creating backups, checking for idle resources, generating reports, and other tasks which frequently occur can be implemented using AWS Lambda.

- Bulk real-time data processing

There are some cases when your application may need to handle large volumes of streaming input data, and moving that data to temporary storage for later processing may not be an adequate solution.If you send the data stream to an AWS Lambda application designed to quickly pull and process the required information, you can handle the necessary real-time tasks.

- Processing uploaded S3 objects

By using S3 object event notifications, you can immediately start processing your files by Lambda, once they land in S3 buckets. Image thumbnail generation with AWS Lambda is a great example for this use case, the solution will be cost-effective and you don’t need to worry about scaling up - Lambda will handle any load.

AWS Lambda limitations

AWS Lambda is not a silver bullet for every use case. For example, it should not be used for anything that you need to control or manage at the infrastructure level, nor should it be used for a large monolithic application or suite of applications.

Lambda comes with a number of “limitations”, which is good to keep in mind when architecting a solution.

There are some “hard limitations” for the runtime environment: the disk space is limited to 500MB, memory can vary from 128MB to 3GB and the execution timeout for a function is 15 minutes. Package constraints like the size of the deployment package (250MB) and the number of file descriptors (1024) are also defined as hard limits.

Similarly, there are “limitations” for the requests served by Lambda: request and response body synchronous event payload can be a maximum of 6 MB while an asynchronous invocation payload can be up to 256KB. At the moment, the only soft “limitation”, which you can request to be increased, is the number of concurrent executions, which is a safety feature to prevent any accidental recursive or infinite loops from going wild in the code. This would throttle the number of parallel executions.

All these limitations come from defined architectural principles for the Lambda service:

- If your Lambda function is running for hours, it should be moved to EC2 rather than Lambda.

- If the deployment package jar is greater than 50 MB in size, it should be broken down into multiple packages and functions.

- If the request payloads exceed the limits, you should break them up into multiple request endpoints.

It all comes down to preventing deploying monolithic applications as Lambda functions and designing stateless microservices as a collection of functions instead. Having this mindset, the “limitations” make complete sense.

AWS Lambda examples

Let’s now take a look at some AWS Lambda examples. We will start with a dummy Java application and how to create, deploy and trigger AWS Lambda. We will use AWS Command Line Interface(AWS CLI) to manage functions and other AWS Lambda resources.

Basic application

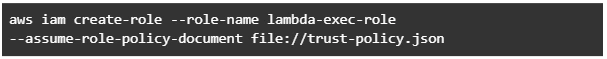

Let’s get started by creating the Lambda function and needed roles for Lambda execution.

This trust policy allows Lambda to use the role's permissions by giving the service principal lambda.amazonaws.com permission to call the AWS Security Token Service AssumeRole action. The content of trust-policy.json is the following:

Then let’s attach some permissions to the created role. To add permissions to the role, use the attach-policy-to-role command. Start by adding the AWSLambdaBasicExecutionRole managed policy.

Function code

As an example, we will create Java 11 application using Maven.

For Java AWS Lambda provides the following libraries:

- com.amazonaws:aws-lambda-java-core – Defines handler method interfaces and the context object that the runtime passes to the handler. This is a required library.

- com.amazonaws:aws-lambda-java-events – Different input types for events from services that invoke Lambda functions.

- com.amazonaws:aws-lambda-java-log4j2 – An appender library for Apache Log4j 2 that you can use to add the request ID for the current invocation to your function logs.

Let’s add Java core library to Maven application:

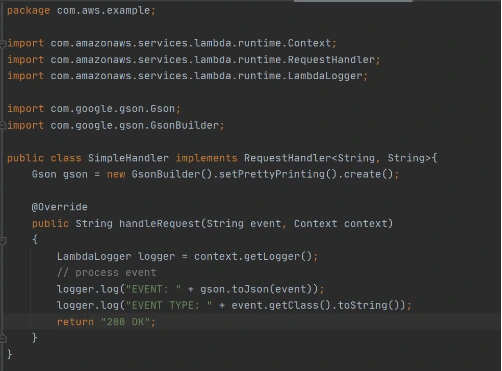

Then we need to add a Handler class which will be an entry point for our function. For Java function this Handler class should implement com.amazonaws.services.lambda.runtime.RequestHandler interface. It’s also possible to set generic input and output types.

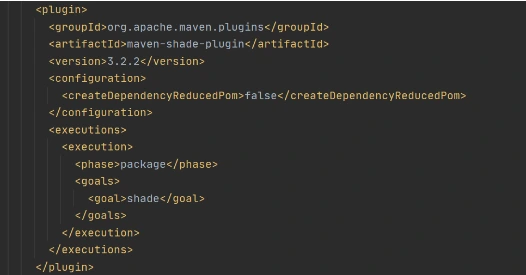

Now let’s create a deployment package from the source code. For Lambda deployment package should be either .zip or .jar. To build a jar file with all dependencies let’s use maven-shade-plugin .

After running mvn package command, the resulting jar will be placed into target folder. You can take this jar file and zip it.

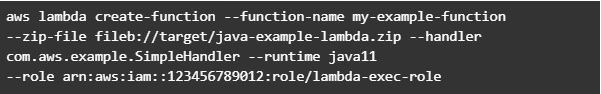

Now let’s create Lambda function from the generated deployment package.

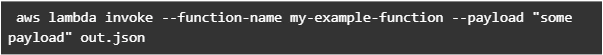

Once Lambda function is deployed we can test it. For that let’s use invoke-command.

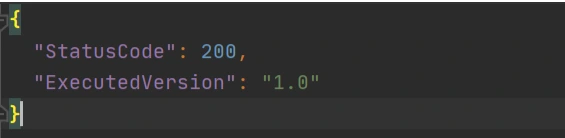

out.json means the filename where the content will be saved. After invoking Lambda you should be able to see a similar result in your out.json :

More complicated example

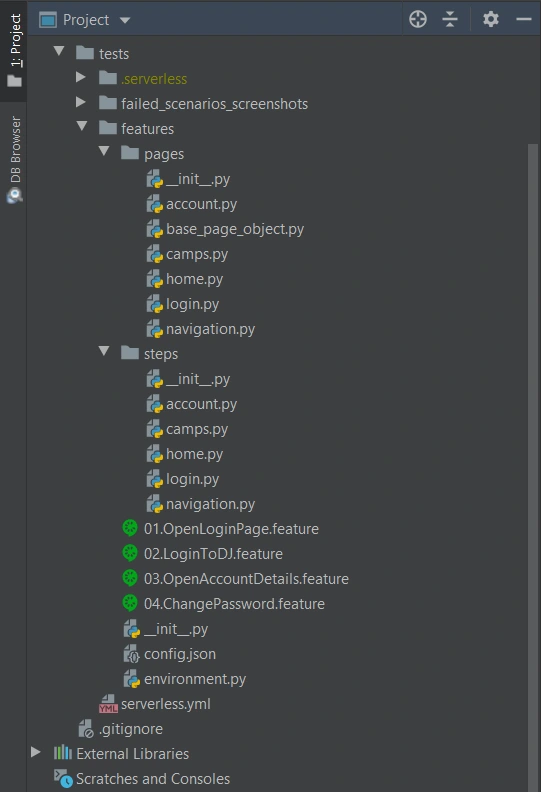

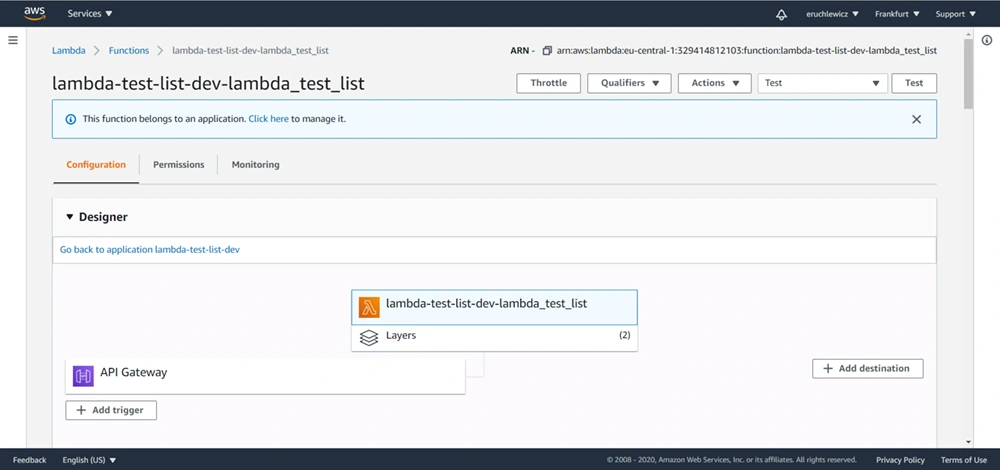

Now let’s take a look at a more complicated application that will show the integration between several AWS services. Also, we will show how Lambda Layers can be used in function code. Let’s create an application with API Gateway as a proxy, two Lambda functions as some back-end logic, and DynamoDB as data storage. One Lambda will be intended to save a new record into the database. The second Lambda will be used to retrieve an object from the database by its identifier.

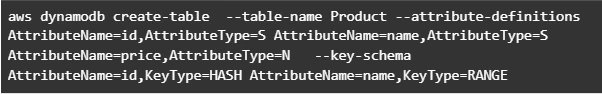

Let’s start by creating a table in DynamoDB. For simplicity, we’ll add just a couple of fields to that table.

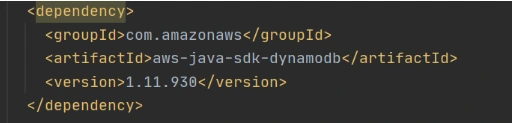

Now let’s create a Java module where some logic with database operations will be put. Dependencies to AWS DynamoDB SDK should be added to the module.

Now let’s add common classes and models to work with the database. This code will be reused in both lambdas.

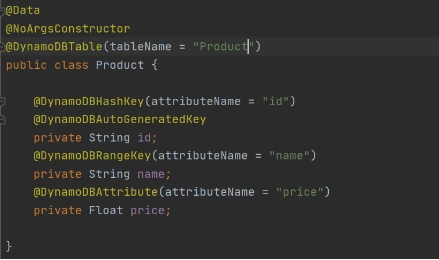

Model entity object:

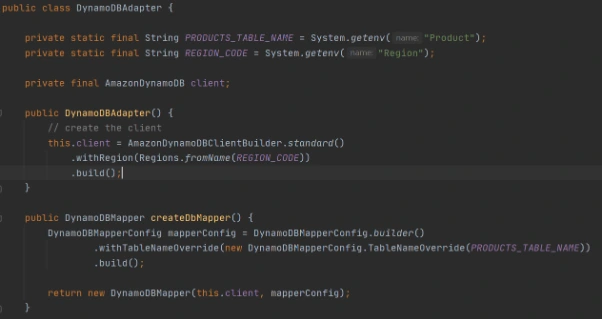

Adapter class to DynamoDB client.

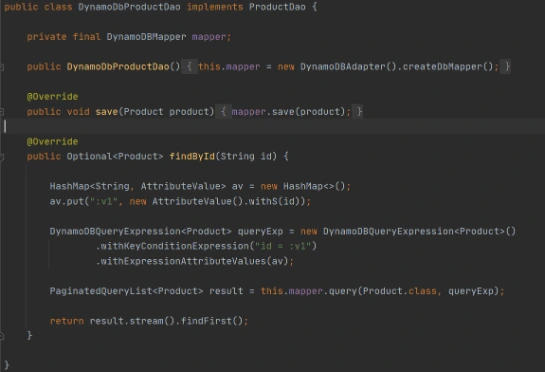

Implementation of DAO interface to provide needed persistent operations.

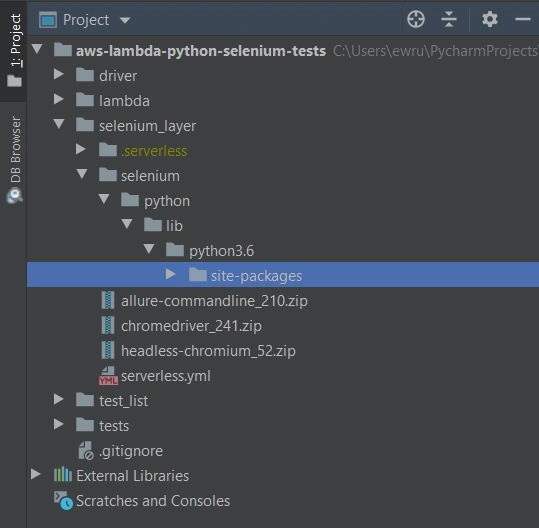

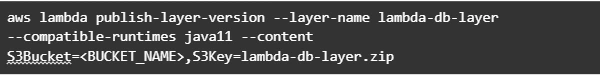

Now let’s build this module and package it into a jar with dependencies. From that jar, a reusable Lambda Layer will be created. Compress fat jar file as a zip archive and publish it to S3. After doing that we will be able to create a Lambda Layer.

Layer usage permissions are managed on the resource. To configure a Lambda function with a layer, you need permission to call GetLayerVersion on the layer version. For functions in your account, you can get this permission from your user policy or from the function's resource-based policy. To use a layer in another account, you need permission on your user policy, and the owner of the other account must grant your account permission with a resource-based policy.

Function code

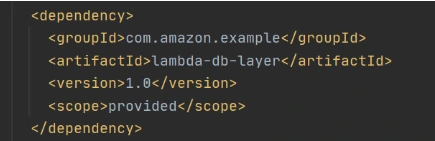

Now let’s add this shared dependency to both Lambda functions. To do that we need to define a provided dependency in pom.xml.

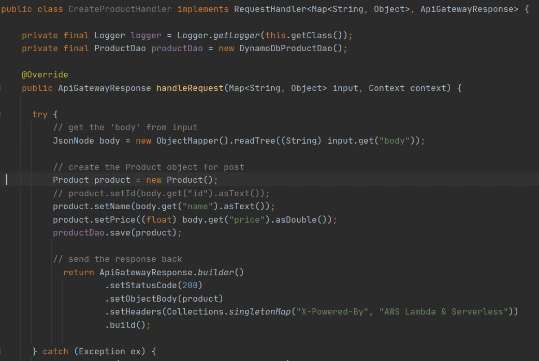

After that, we can write Lambda handlers. The first one will be used to persist new objects into the database:

NOTE : in case of subsequent calls AWS may reuse the old Lambda instance instead of creating a new one. This offers some performance advantages to both parties: Lambda gets to skip the container and language initialization, and you get to skip initialization in your code. That’s why it’s recommended not to put the creation and initialization of potentially reusable objects into the handler body, but to move it to some code blocks which will be executed once - on the initialization step only.

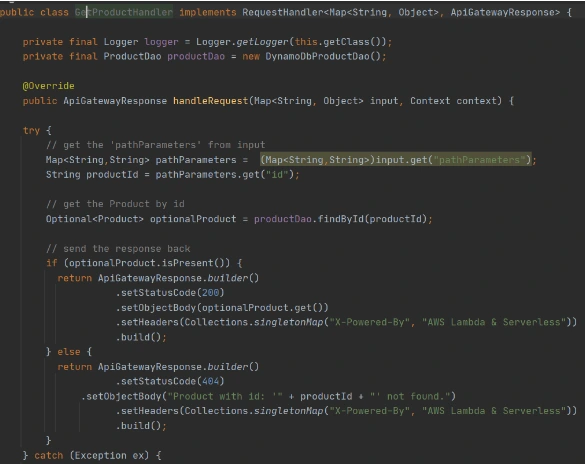

In the second Lambda function we will extract object identifiers from request parameters and fetch records from the database by id:

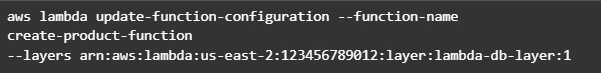

Now create Lambda functions as it was shown in the previous example. Then we need to configure layer usage for functions. To add layers to your function, use the update-function-configuration command.

You must specify the version of each layer to use by providing the full Amazon Resource Name (ARN) of the layer version. While your function is running, it can access the content of the layer in the /opt directory. Layers are applied in the order that's specified, merging any folders with the same name. If the same file appears in multiple layers, the version in the last applied layer is used.

After attaching the layer to Lambda we can deploy and run it.

Now let’s create and configure API Gateway as a proxy to Lambda functions.

This operation will return json with the identifier of created API. Save the API ID for use in further commands. You also need the ID of the API root resource. To get the ID, run the get-resources command.

Now we need to create a resource that will be associated with Lambda to provide integration with functions.

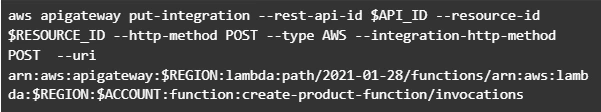

Parameter --integration-http-method is the method that API Gateway uses to communicate with AWS Lambda. Parameter --uri is a unique identifier for the endpoint to which Amazon API Gateway can send requests.

Now let’s make similar operations for the second lambda( get-by-id-function ) and deploy an API.

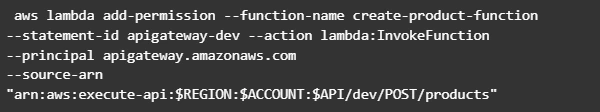

Note. Before testing API Gateway, you need to add permissions so that Amazon API Gateway can invoke your Lambda function when you send HTTP requests.

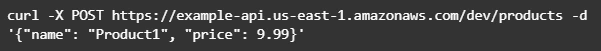

Now let’s test our API. First of all, we’ll try to add a new product record:

The result of this call will be like this:

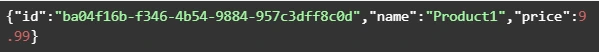

Now we can retrieve created object by its identifier:

And you will get a similar result as after POST request. The same object will be returned in this example.

AWS Lambda tips

Debugging Lambda locally

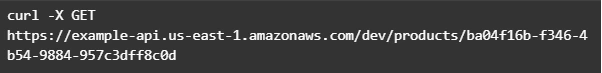

You can use AWS SAM console with a number of AWS toolkits to test and debug your serverless applications locally. For example, you can perform step-through debugging of your Lambda functions. The commands sam local invoke and sam local start-api both support local step-through debugging of your Lambda functions. To run AWS SAM locally with step-through debugging support enabled, specify --debug-port or -d on the command line. For example:

Also for debugging purposes, you can use AWS toolkits which are plugins that provide you with the ability to perform many common debugging tasks, like setting breakpoints, executing code line by line, and inspecting the values of variables. Toolkits make it easier for you to develop, debug, and deploy serverless applications that are built using AWS.

Configure CloudWatch monitoring and alerts

Lambda automatically monitors Lambda functions on your behalf and reports metrics through Amazon CloudWatch. To help you monitor your code when it runs, Lambda automatically tracks the number of requests, the invocation duration per request, and the number of requests that result in an error. Lambda also publishes the associated CloudWatch metrics. You can leverage these metrics to set CloudWatch custom alarms. The Lambda console provides a built-in monitoring dashboard for each of your functions and applications. Each time your function is invoked, Lambda records metrics for the request, the function's response, and the overall state of the function. You can use metrics to set alarms that are triggered when function performance degrades, or when you are close to hitting concurrency limits in the current AWS Region.

Beware of concurrency limits

For those functions whose usage scales along with your application traffic, it’s important to note that AWS Lambda functions are subject to concurrency limits. When functions reach 1,000 concurrent executions, they are subject to AWS throttling rules. Future calls will be delayed until your concurrent execution averages are back below the threshold. This means that as your applications scale, your high-traffic functions are likely to see drastic reductions in throughput during the time you need them most. To work around this limit, simply request that AWS raise your concurrency limits for the functions that you expect to scale.

Also, there are some widespread issues you may face working with Lambda:

Limitations while working with database

If you have a lot of reading/writing operations during one Lambda execution, you may probably face some failures due to Lambda limitations. Often the case is a timeout on Lambda execution. To investigate the problem you can temporarily increase the timeout limit on the function, but a common and highly recommended solution is to use batch operations while working with the database.

Timeout issues on external calls

This case may occur if you call a remote API from Lambda that takes too long to respond or that is unreachable. Network issues can also cause retries and duplicated API requests. To prepare for these occurrences, your Lambda function must always be idempotent. If you make an API call using an AWS SDK and the call fails, the SDK automatically retries the call. How long and how many times the SDK retries is determined by settings that vary among each SDK. To fix the retry and timeout issues, review the logs of the API call to find the problem. Then, change the retry count and timeout settings of the SDK as needed for each use case. To allow enough time for a response to the API call, you can even add time to the Lambda function timeout setting.

VPC connection issues

Lambda functions always operate from an AWS-owned VPC. By default, your function has full ability to make network requests to any public internet address — this includes access to any of the public AWS APIs. You should configure your functions for VPC access when you need to interact with a private resource located in a private subnet. When you connect a function to a VPC, all outbound requests go through your VPC. To connect to the internet, configure your VPC to send outbound traffic from the function's subnet to a NAT gateway in a public subnet.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.