Automation testing: Making tests independent from existing data

Each test automation project is different. The apps are different, the approach is different, even though the tools and frameworks used might seem to be the same. Each project brings different challenges and requirements, resulting in a need to adapt to solutions being delivered - although all of it is covered by the term "software testing". This time we want to tackle the issue of test data being used in automation testing.

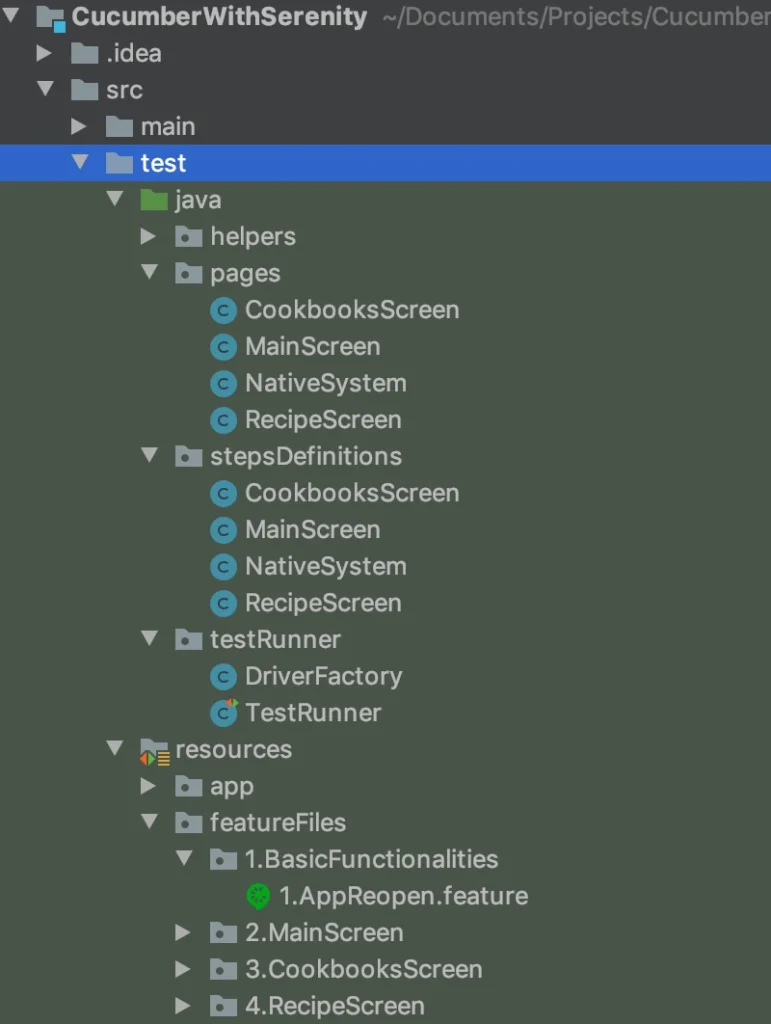

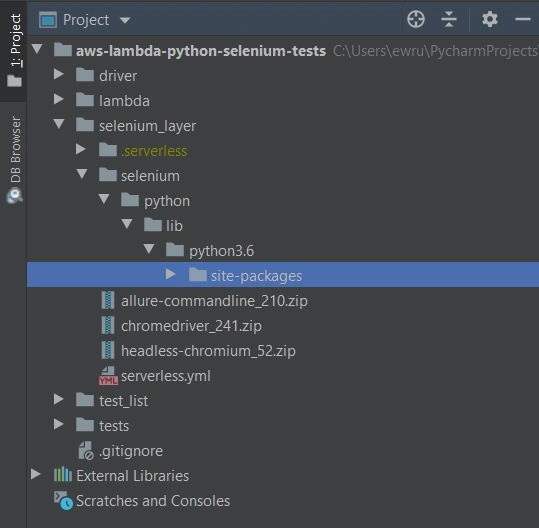

Setting up the automation testing project

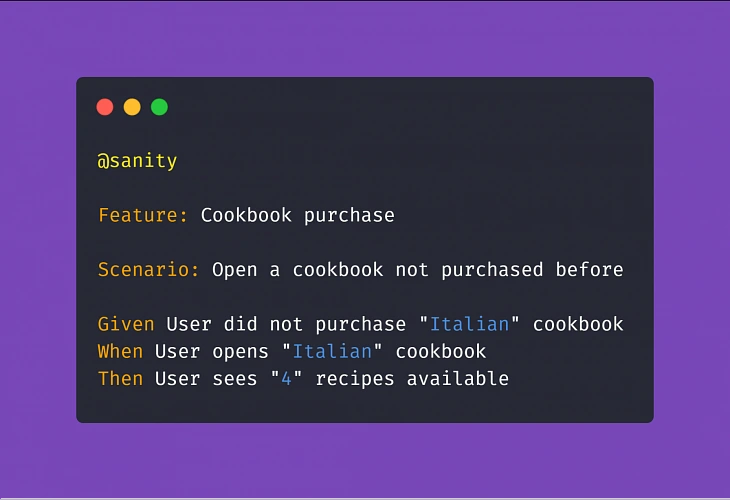

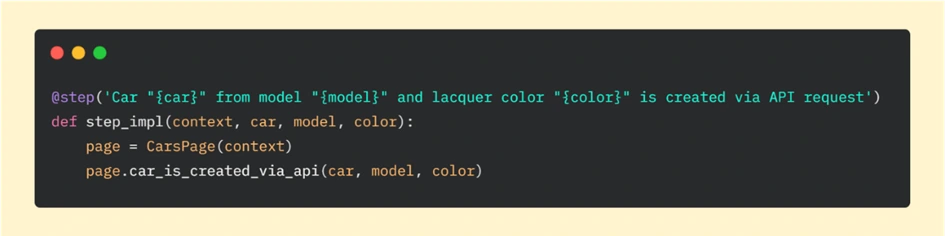

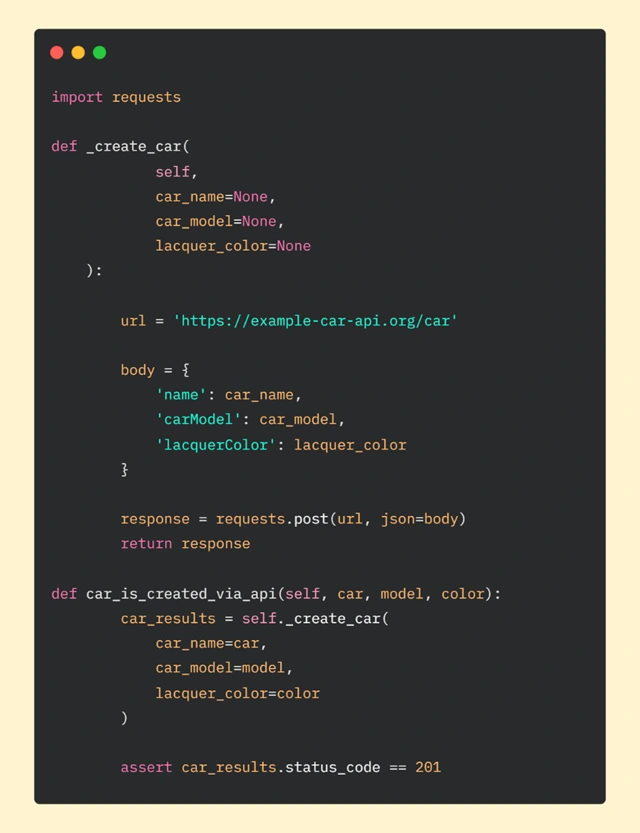

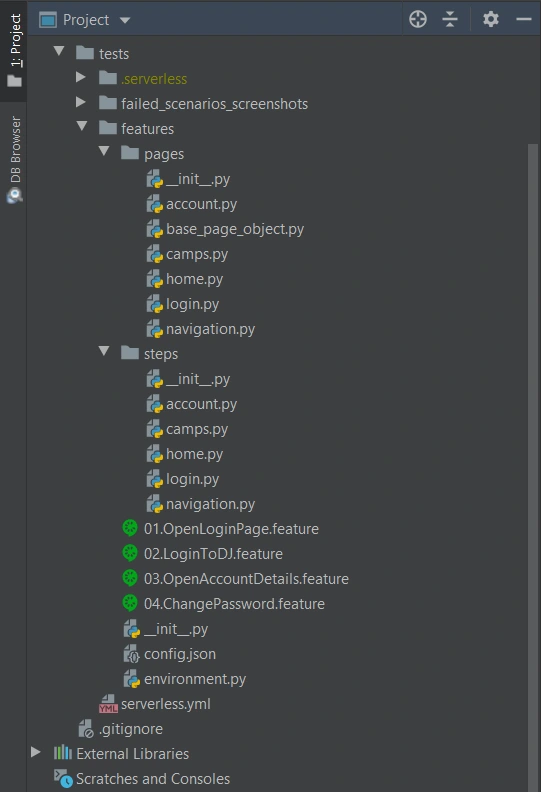

Let's consider the following scenario: as usual, our project implements the Page Object Pattern approach with the use of Cucumber .). This part is no novelty - tidy project structure and test scenarios written in Gherkin, which is easily understandable by non-technical team members. However, the application being tested required total independence from data existing in the database, even in Development and QA environments.

The solution implemented by our team had to ensure that every Test Scenario - laid out in each Feature File, which contains steps for testing particular functionalities, was completely independent from data existing on the environment and did not interfere with other Test Cases. What was also important, the tests were also meant to run simultaneously on Selenium Grid. In a nutshell, Feature Files couldn't rely on any data (apart from login credentials) and had to create all of the test data each time they were run.

To simplify the example we are going to discuss, we will describe an approach where only one user will be used to log in to the app. Its credentials remain unchanged so there are two things to do here to meet the project criteria: the login credentials have to be passed to the login scenario and said scenario has to be triggered before each Feature File since they are run simultaneously by a runner.

Independent logging in

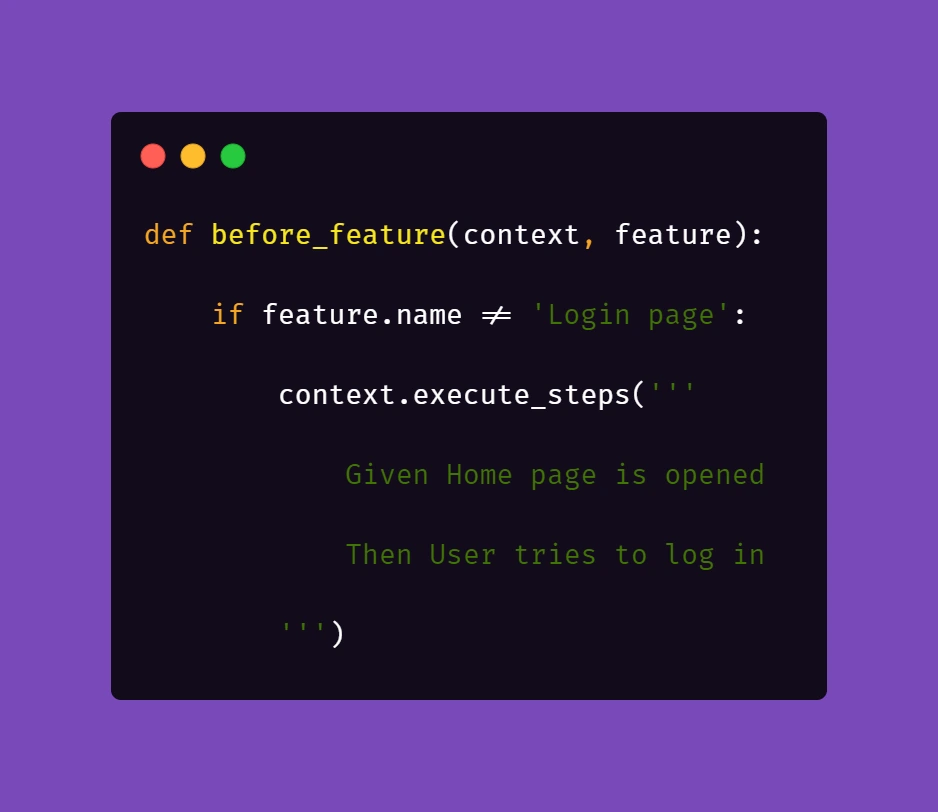

The first part is really straightforward; in your environment file you need to include a similar block of code:

What this does is, before each feature file, which is not a Login scenario, Selenium will attempt to open the homepage of the project and attempt to log in.

Then, we need to ensure that if a session is active, logging in should be skipped.

Therefore, in the second step 'User tries to log in' we verify if within the instance of running a particular feature file, the user's session is still active. In our case, when the homepage is opened and a logged user's session is active, the app's landing page is opened. Otherwise, the user is redirected to the login page. So in the above block of code we simply verify whether the login page is opened and if login_prompt_is_displayed method returns True , login steps are executed.

Once we dealt with logging in during simultaneous test runs, we need to handle the data being used during the tests. Again, let us simplify the example: let's assume that our hypothetical application allows its users - store staff - to add and review products the company has to offer. The system allows manipulating many data fields that affect other factors in workflows, e.g. product bundles, discounts, and suppliers. On top of that, the stock constantly grows and changes, thus even in test environments we shouldn't just run tests against migrated data to ensure consistency in test results.

As a result of that, our automation tests will have to cover the whole flow, adding all the necessary elements to the system to test against later on. In short: if we want to cover a scenario for editing certain data in a product, the tests will need to create that specific product, save it, search for it, manipulate the data, save changes and verify the results.

Create and manipulate

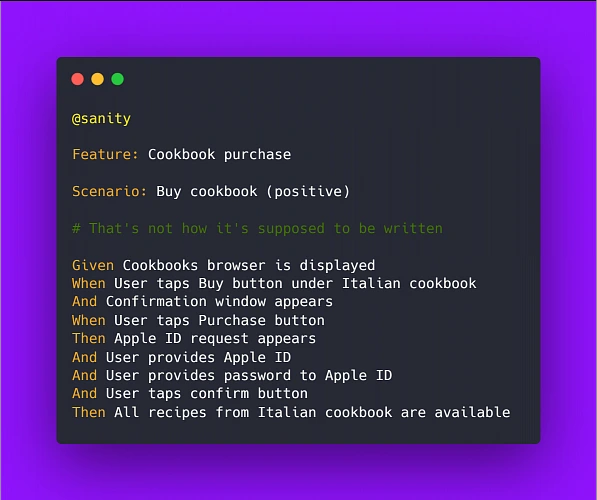

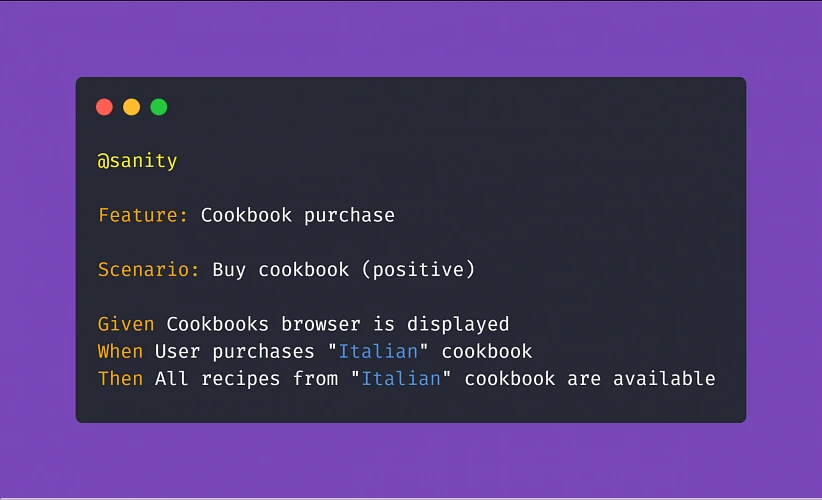

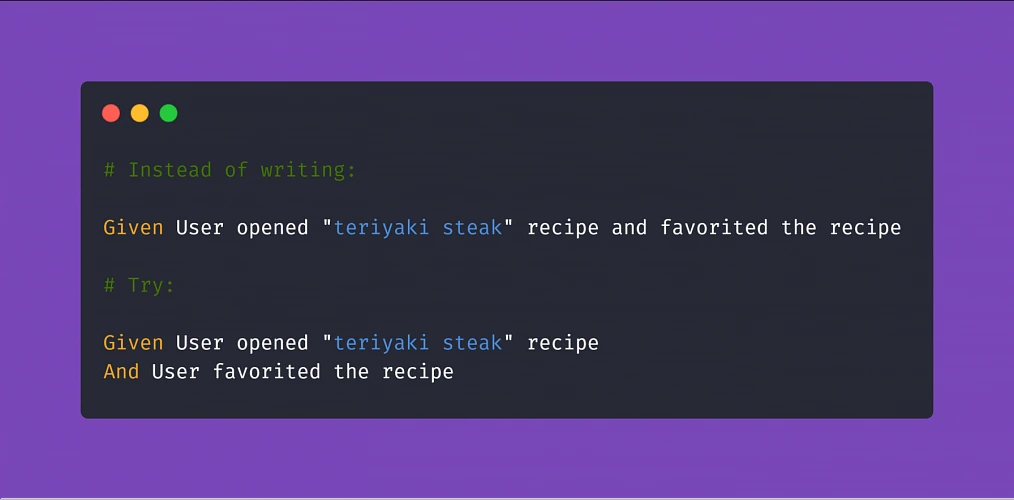

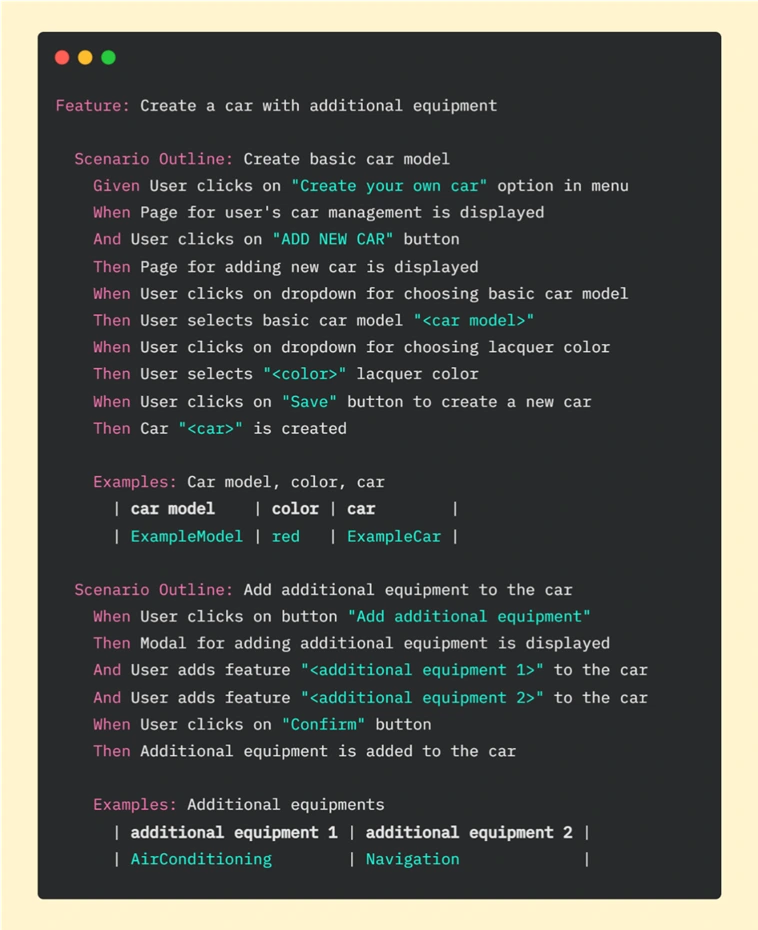

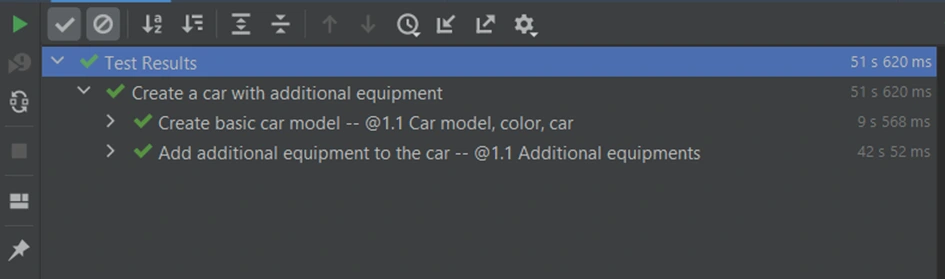

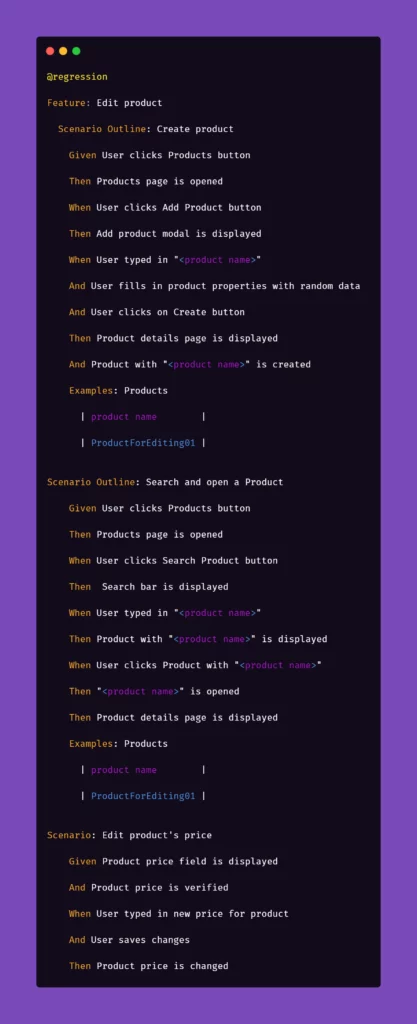

Below are the test steps to the above scenario laid out in Gherkin to illustrate what will it look like:

While the basic premise of the above scenarios may seem straightforward, the tricky part may be ensuring consistency during test runs. Of course, scripting a single scenario of adding an item in the app sounds simple, but what if we would have to do that a couple dozens of time during the regression suite run?

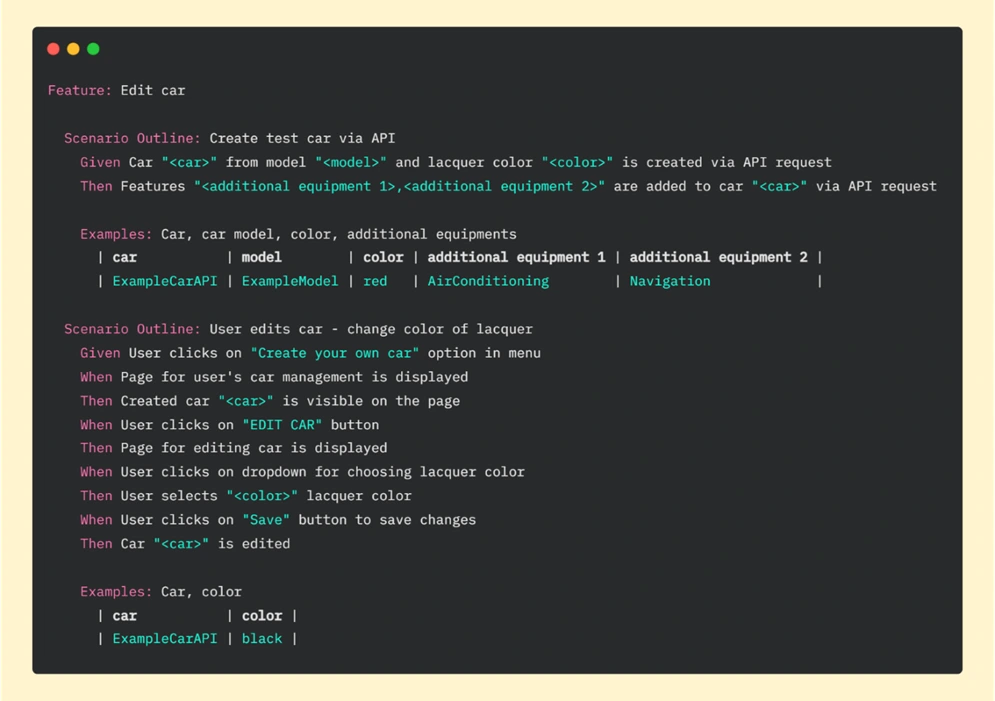

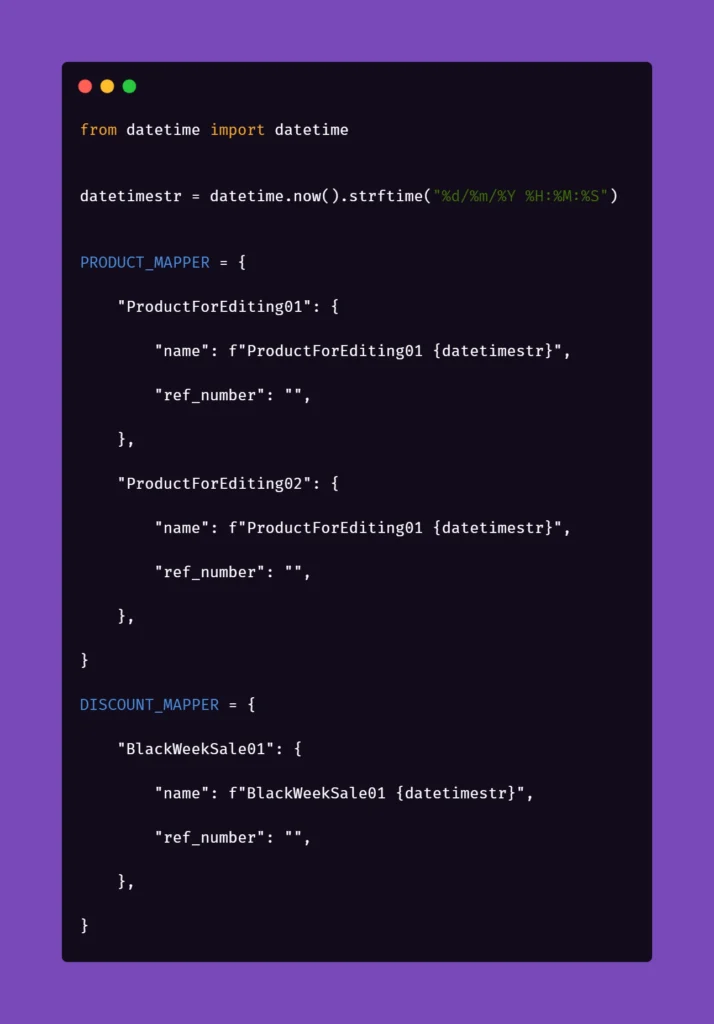

We want to have consistent, trackable test data while avoiding multiplying lines of code. To achieve that, we introduced another file to the project structure called 'globals' and placed it in the directory of feature files. Please note that in the above snippet, we extensively use "Examples" sections along with the "Scenario Outline" approach in Gherkin. We do that to pass parameters into test step definitions and methods that create and manipulate the actions we want to test in the application. That first stage of parametrization of a test scenario works in conjunction with the aforementioned 'globals' file. Let's consider the following contents of such file:

Inside the ‘globals’ file, you can find mappers for each type of object that the application can create and manipulate, for now including only a name and a reference number as an empty string. As you can see, each element will receive a datetime stamp right after its core name, each time the object in the mapper is called for. That will ensure the data created will always be unique. But what is the empty string for, you may ask?

The answer is as simple as its usage: we can store different parameters of objects inside the app that we test. For example, if a certain object can be found only by its reference number, which is unique and assigned by the system after creating, e.g., a product, we might want to store that in the mapper to use it later. But why stop there? The possibilities go pretty much as far as your imagination and patience go. You can use mappers to pass on various parameters to test steps if you need:

As you can see, the formula of mappers can really come in handy when your test suite needs to create somewhat repeatable, custom data for tests. The above snippet includes parameters for the creation of an item in the app which is a promotional campaign including certain types of products. Above that, you can see a mapping for a product that falls into one of the categories qualifying it for the promotional campaign. So hypothetically, if you want to test a scenario where enabling a promotional campaign will automatically discount certain products in the app, the mapping could help with that. But let's stick to basic examples to illustrate how to pass these parameters into the methods behind test steps.

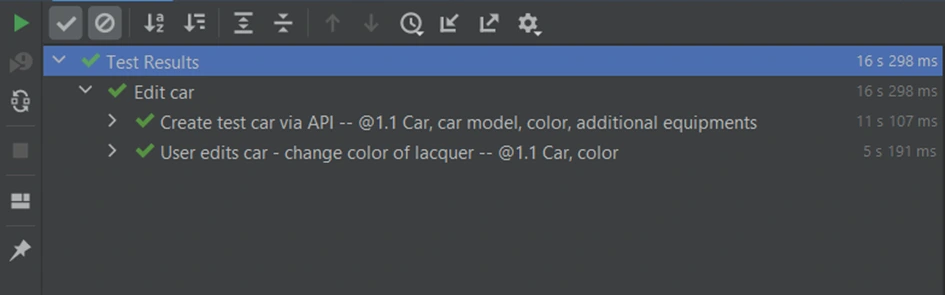

Let us begin with the concept of creating products mentioned in the Gherkin snippet. Below is the excerpt from /steps file for step "User typed in "<product name>"":

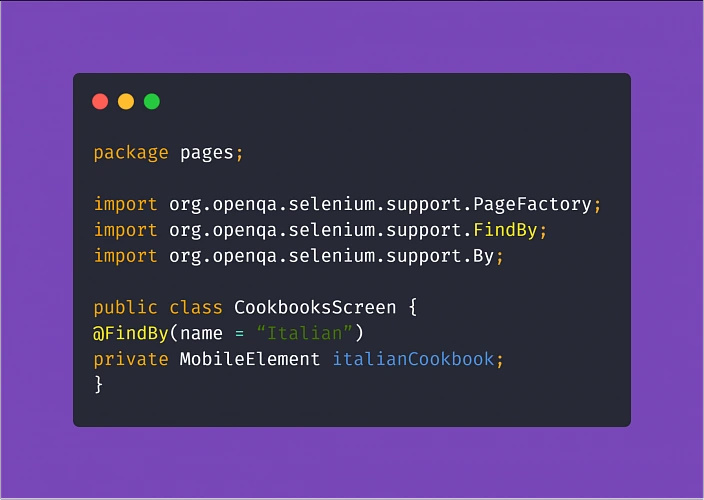

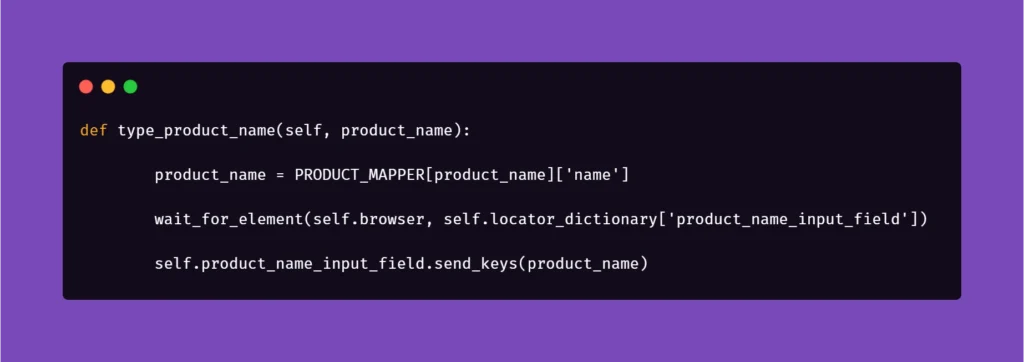

Above, we just simply pass the parameter from Gherkin to the method. Nothing fancy here. But it gets more interesting in /pages file:

First, you'll need to import a globals file to get to the data mapped out there:

Next, we want to extract the data from mapper:

Basically, the name for the product inputted in the Examples section in Scenario Outline matches the name in PRODUCT_MAPPER . Used as a variable, it allows Selenium to input the same name with a timestamp each time the scenario asks for the creation of a certain object. This concept can be used quite extensively in the test code, parameterizing anything you need.

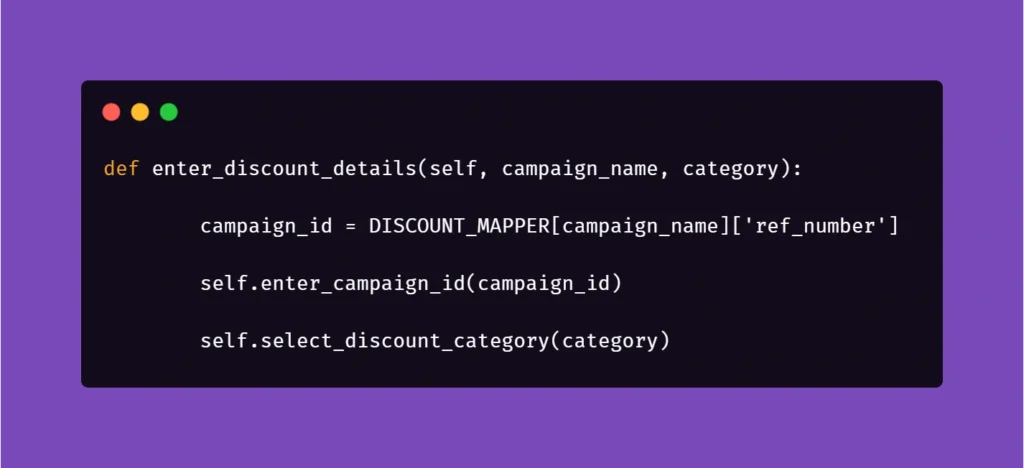

And another example:

Here, we get the data from mapper to create a specific locator to use in a specific context. This way, if the app supports it, test code can be reduced due to parametrization.

We hope that the concepts presented in this article will help you get on with your work on test automation suites. These ideas should help you automate tests faster, more clever, and much more efficiently, resulting in maximum consistency and stable results.

Grape Up guides enterprises on their data-driven transformation journey

Ready to ship? Let's talk.

Check related articles

Read our blog and stay informed about the industry's latest trends and solutions.

Interested in our services?

Reach out for tailored solutions and expert guidance.